# Bodhas

The Intellectual Traditions of the East For Beginners, Part 7 | The Sāṅkhya School

16 March, 2025

5117 words

share this article

This is Part 7 of a series of articles on Eastern Philosophy. Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, and Part 6. The individual articles in this series are written so that they are self contained but occasionally may refer to older articles for some details.

Last time we saw the anti-substance philosophy of Nāgārjuna who belonged to the Mādhyamaka school of Mahāyāna Buddhism. Before that, we also explored the Mīmāṃsā school of Hinduism. Let us continue sampling various interesting topics from various thinkers in various schools. In this article, I will elaborate on an important Hindu school of philosophy called the Sāṅkhya school. Before that, it is important to learn about the notion of mind and matter dualism in Western philosophy so that one realizes how it is fundamentally different from the dualism that is promulgated by the Sāṅkhya school.

Mind vs Matter - Western Dualism

Look around you. What do you perceive in general? Maybe, a stone? We all agree that the stone is a material, made of matter. You see a stone. Can I also see that stone that you are seeing? Yes, obviously. At least on an intuitive level. You feel wind blowing on your face. If I am also standing there, would you agree that I can also feel the wind blowing on my face? Yes, again and obviously you may say. You can see your legs. So can I. You can see a flower. So can I. That is what, everyone would agree on the level of common sense - there is a material reality made of material objects or matter. It occupies space and exists in time. And that reality looks objective - everyone can see it and agree about its existence. The underlying assumption of science is that there is an objective reality of matter or material world that is perceived identically by all human beings, thanks to the gift of rationality. The objective of science is to discover the laws that govern this world of matter. And the success of modern science should be enough testament to increase our confidence about the existence of this objective material reality that is made of matter and can be perceived by all observers.

So, I ask you a simple question now. Imagine all possible things that you can see, feel and perceive. Is it all material - are all that you can see or feel, solely material objects occupying a location in space and time and that which can be felt by others also? Let me list some things that you can feel.

List 1 (Red):

- Stone

- Fruit

- Your leg

- Your brain

List 2 (Violet):

- Your pain

- Your sight of the fruit, stone, your leg,…

- Your hearing of a beautiful song or a horrible noise

- Your happiness

One would agree that the items in the red list (first four) are material and that they can be felt by you but also can be felt by everybody. It includes stuff around you and even your body - with advanced scanning devices for aid, everyone can see what your brain or your eye looks like. So the stuff in the red list are - material (made of matter that occupies space and time) and objective (perceivable by all). Common sense tells us that such material objects exist independently of anyone looking at it. That is what being objective technically means.

But on the other hand, the objects in the violet list (the last four), are immensely personal. I can see the flower you are seeing. But I cannot feel that visual experience that you get when you see the same flower that I see. Again, I can take a sophisticated live brain scan and experience that spark of neurons that fire when you see the flower - that is not denied. But your own personal visual experience that you feel while seeing that flower cannot be seen or felt by me. Again, as you see that flower, I can track and perceive the signals that go on from your retina to the optic nerve and finally to the visual cortex of your brain via sophisticated scanning and imaging techniques. But your own conscious visual experience that you feel - the visual feeling when you see the flower - that you would agree - is immensely personal. Nobody else has access to it other than you. Others can access material correlates of that visual process - in your brain signals or your retina but they cannot exactly do your seeing. The same is for your pain. I can observe the neural correlates of your pain and even measure it when you are experiencing it - but I cannot feel your pain at all. I cannot feel your pain and you cannot feel mine. Period. So in some sense, empathy is not possible in its truest sense of being capable of feeling another person’s pain or happiness.

It turns out that Western philosophy sees the world split into two different camps - an objective material world and a subjective mental world. This is what is called the mind-body duality with-

- the body standing for matter or the objective world that you perceive which everyone has access to

- the mind standing for personal experiences or your subjective world which only you have access to

This is how the duality of Western philosophy stands - an objective material world of matter independently existing and accessible to everyone and a subjective mental world of experiences and thoughts that is immensely personal and can be accessed only by the person concerned.

Now, Western philosophers have long argued that whether this dualism that comes about is really so. There are roughly three camps

Materialism

In this school, the materialists believe that only the material world is real. They argue that only material objective reality exists. And what we think of as subjective reality is basically a complex interplay of the materials constituting your body. i.e. all that exists are materials in the red camp - like stones, water, your eye, your brain. They argue that ultimately any experience that one regards as personal - eg. the visual feeling that you get when you see a stone - is basically a result of a complex set of interactions between the stone, your eyes, and your brain. That your personal perception of the brain is nothing but the result of the photons coming from the stone and absorbed by the cells of the retina and the resulting signal being transferred via the optic nerve to the visual cortex in the brain where some neurons are fired. According to the materialists, your personal feelings are nothing more than a name given to a bunch of material processes - there is nothing more to personal feelings than the physiology of your body and its interaction with the matter outside. They hypothesize that there is no such thing as personal subjective experience - if science advances enough, and with hard enough computation, we can pin down the materialistic bases of subjective experience and there is nothing more to your pains and pleasures than the collection of all material processes that are happening in your body.

The empiricists contend that I cannot exactly access your personal feelings simply because science has not advanced enough - the concept of your personal feelings is an illusion - the personal feeling of your pain is basically equal to the sum total of everything that happens in your body as it interacts with surroundings. Materialists challenge that if I understand all that happens in your body (with advanced science), I can understand everything about your personal feelings. A private personal world of feelings is an illusion according to empiricists.

Idealism

On the other side of the camp are idealists - they argue for the exact opposite. They argue that all that we can be really sure about are our own personal feelings. I get a feeling of the chair when I see it. But what is solid and what is concrete is my personal subjective visual experience of the chair. I have no basis to claim that my personal visual experience is the result of a material chair that exists objectively even if I don’t see it. It goes back to a famous saying by Einstein - does the moon really exist when nobody is looking at it?

Idealists claim that what is securely confirmable are our personal feelings and subjective experiences. That my personal experiences are the result of a material reality that exists objectively - is merely a supposition or a hypothesis or a theory - according to the idealists. The hypothesis that there exists an actual chair independently when I see one, is basically an ingrained theory that we develop because it makes life simple and explains the fact that many of our perceptions are coordinated - i.e. you and I can both agree that we are seeing the same kind of chair when we open our eyes in a room with a chair. So we postulate that such co-ordinations in our visual perception is not because the same visual feeling of a chair is created in both of our personal spaces - but because there exists a chair independently from both of us - which upon interaction with our personal realm causes us to have a perception of that chair. Idealists say that all I experience and be sure about are my personal feelings and hence I cannot postulate that they come from an objective world of matter.

A famous argument for idealism comes from the movie, The Matrix, where intelligent robots have overpowered humans and put them in a tube and feed into their brains those exact signals that they would get if they lived in a real world of material objects. And nobody in that movie realizes that they are in this illusionary world - i.e. what they are experiencing is not the result of perception of a material world but due to coordinated brain signals from the robots that mimic the exact same signals coming from a material world. So, the concept of an objective material world of matter is at best a hypothesis or at worst an illusion, according to idealists. Even if there were such an objective reality, the only way I can access that reality is through my subjective experience of it. So, some philosophers (like Kant) believe that the world that is independent of our senses is inaccessible even though it may exist. So, we cannot say anything about it. Such a position is called transcendental idealism.

Dualists

In this camp, the dualists believe that both the subjective and objective world really exist and one cannot be subsumed by the other. They claim that our common sense intuition of there being an objective world and a subjective experience of it - both are too secure to be denied. So according to the dualists - there are two components to us - the body which constitutes the material physiology of us - but also a mental world or the mind which exists (not as a part of the body) and is responsible for our personal feelings and is inaccessible to others. According to the dualists, we have both a material as well as a mental component and no one can be complete without their personal mind and material body. Both our mind and the body interact with each other in this picture . The mind wills that makes the body act according to the will and influence material objects around us (eg. when we will personally decide to move the chair and the material chair moves). The material world interacts with our mind through our perception process - the material chair interacts with the mind to make us actually feel the personal experience of us seeing the chair. In this scenario, both the mental and the material worlds are separate and have a real existence.

There are so many debates between these three camps which I will go into on other posts. but now I return to ancient India and how Indian thought drew the line that separates two things.

Prakṛti vs Puruṣa - Indian Dualism

Ancient Indian philosophical tradition also has a dualistic worldview in its viewpoints, but it is very different from that of the West. It is surprisingly deeper, and not definitely commonsensical as the mind-matter duality of the West. This dualistic division in Indian philosophy is so central to all the Indian schools and practices that have developed and is an integral part of Indian culture. The Sāṅkhya school calls those two ends of the duality by two Saṃskṛta names.

On one side of the divide is prakṛti. Prakṛti is normally translated as nature or the realm of the natural world. But surprisingly, prakṛti in the Indian side not only includes the material reality made of matter but also all of our personal observable experiences - whether objective or subjective, physical objects or mental states!! What in the West goes into two camps - a material objective world and a personal subjective world is dumped into a single side - the side of the observed. In other words,

Prakṛti = the source of all of that which can be observed (material and mental)

The Indian mind did not seek to discern whether something that I observe can be observed by everyone else or not. The ancient Indian mind did not think of objectivity vs subjectivity as an important distinction. It did not bother whether what I feel and perceive is personal or something that can be felt by everyone. Both of these are just observable things. Period.

So, if prakṛti is the source of all that is observed by you - then what exists on the other side of the duality in Indian thought?

The Indian mind wondered - is there something more in me than whatever I observe? Take all the observable experiences that anyone had, is having, and could ever have. Is that all there is to reality? Is there anything to this world apart from the observables - the world of matter and thoughts?

The Sāṅkhya school calls it the Puruṣa - the observer or the silent and passive witness to all this observable reality. This is similar to the notion of the ātman from the Upaniṣads - the subject that underlies all objects of awareness. The difference is of course that while the notion of ātman comes from inquiry regarding the factor that persists in an individual’s life, the notion of puruṣa comes from inquiry regarding the witness or consciousness that is the subject observer to everything that is observed.

Puruṣa never acts. It just observes. Prakṛti never is reflexive. It just acts. But both are fundamental irreducible principles in the world. One cannot be reduced to the other. But everything that exists can be ontologically reduced to these two. The Sāṅkhyakārikābhāṣya (SK) gives a metaphor for this partnership between Prakṛti and Puruṣa. It is like a partnership between the blind man who can move but not see (Prakṛti) and a lame man who can see but not move (Puruṣa).

Sāṅkhya: History and Source Texts

The word Sāṅkhya is derived from the word saṅkhyā that means “number” or “count” or “enumeration”. This is because, as we will soon see, this school enumerates a list of all fundamental categories. Tradition has it that the Sāṅkhya school was founded by a sage named Kapila. The epic Mahābhārata mentions Sāṅkhya-yoga, a school taught by the sages Kapila, A̅suri, and Pañcaśikha. The influences of Sāṅkhya school are found in the Bhagavad Gītā and also in Āyurveda.

The foundational text of this school is again a sūtra but it is called by the name of Sāṅkhyakārikā, attributed to an author named Īśvarakṛṣṇa. The most important commentary to this text is by Gauḍapāda and is called as Sāṅkhyakārikābhāṣya (SK). If you remember, Gauḍapāda is also the name of the guru of the guru of Śaṅkarācārya. It is possible that both names refer to the same person. What is sure is that Śaṅkara himself had it in for the Sāṅkhya school where he sternly criticizes the whole approach taken by Īśvarakṛṣṇa and his successors. Śaṅkara himself considers the Sāṅkhya school as his main opponent, and he would propose a non-dualist (advaita) monist alternative (Brahman only) to the dualism of the Sāṅkhya school (Puruṣa and Prakṛti), while agreeing with its broad frameworks. Another familiar name from those who wrote commentaries on SK is Patañjali who is very unlikely to be the same person as the grammarian who wrote commentaries on Pāṇini’s grammar sūtras or the author of the Yogasūtras. Other important commentaries to the SK are Yuktidīpīkā and Vācaspati’s Sāṅkhyatattvakaumudī. The Sāṅkhyapravacanasūtra is also among the most important commentaries which invited further commentaries like Aniruddha’s Sāṅkhyasūtravṛtti and Vijñānabhikṣu’s Sāṅkhyapravacanabhāṣya.

The Sāṅkhya View of Causation in Prakṛti

What does it mean to say “X causes Y”? What does it mean when I say that “X is the cause of Y” and “Y is the effect of X”? Causation was a fundamental concern for all Indian schools (except the materialist Cārvāka school) because both the notion of karma and the possibility of liberation all depend on certain actions causing certain effects in the future.

The Sāṅkhya’s theory of causation is conventionally summarized in Saṃskṛta by two words - satkāryavāda and pariṇāmavāda. According to Sāṅkhya, something cannot come from nothing. Existence cannot come from non-existence. This seems commonsensical. So, Sāṅkhya holds that nothing comes into being that was not already present in some form. The standard examples it gives are milk becoming curd and clay becoming pot. According to satkāryavāda, the curd was already present in a potential form within the milk. The curdling agent makes this potential curd manifest when it comes into contact with the curd. Similarly, there resides within the clay, the pot in a latent form, which becomes manifest by the action of a potter. Thus, the effects are transformations of the causes - they do not involve the generation of something brand new. This view of effects as transformations of their causes is called by the technical name of pariṇāmavāda.

Where does this view lead? The pot is latent in its material cause - the clay. The clay is inherent in its cause - earth’s soil. Thus, breaking down everything like this, we see that we keep getting a regress. If we keep carrying on with this regress and chase behind causes of everything, we finally end up with the fundamental primordial elements. This is the technical definition of Prakṛti in the Sāṅkhya school. Prakṛti is the primordial undifferentiated state of existence that is the receptacle of everything in the cosmos. Prakṛti is the primal, fundamental, eternal, and uncaused material principle that serves as the source cause of all manifestation in the universe. It is the primordial “stuff” of existence—material, energetic, and potential—capable of transforming into the multiplicity of the universe while remaining fundamentally unchanged in its essence. Verse 16 of the SK describes it as the “unmanifested cause of the manifold” (avyakta kāraṇa) and contrasts it with Puruṣa, which is unchanging and aware.

Then comes the question, what was that which triggered the transformation of Prakṛti and what are the fundamental principles governing them? The SK gives an elaborate cosmology that is kind of like a mechanistic creation account of the universe.

The Dance of Prakṛti- Sāṅkhya’s Cosmogony

A cosmogony is basically a fancy name for a creation account. There are three principles governing the transformation processes happening in Prakṛti. These words are potent and have various meanings and hence I choose to not translate them from Saṃskṛta.

- Sattva = trueness, being, lightness, purity, harmony, knowledge

- Rajas = passion, change, upheaval, dynamics, activity

- Tamas = inertia, heaviness, dullness, resistance, stability, ignorance

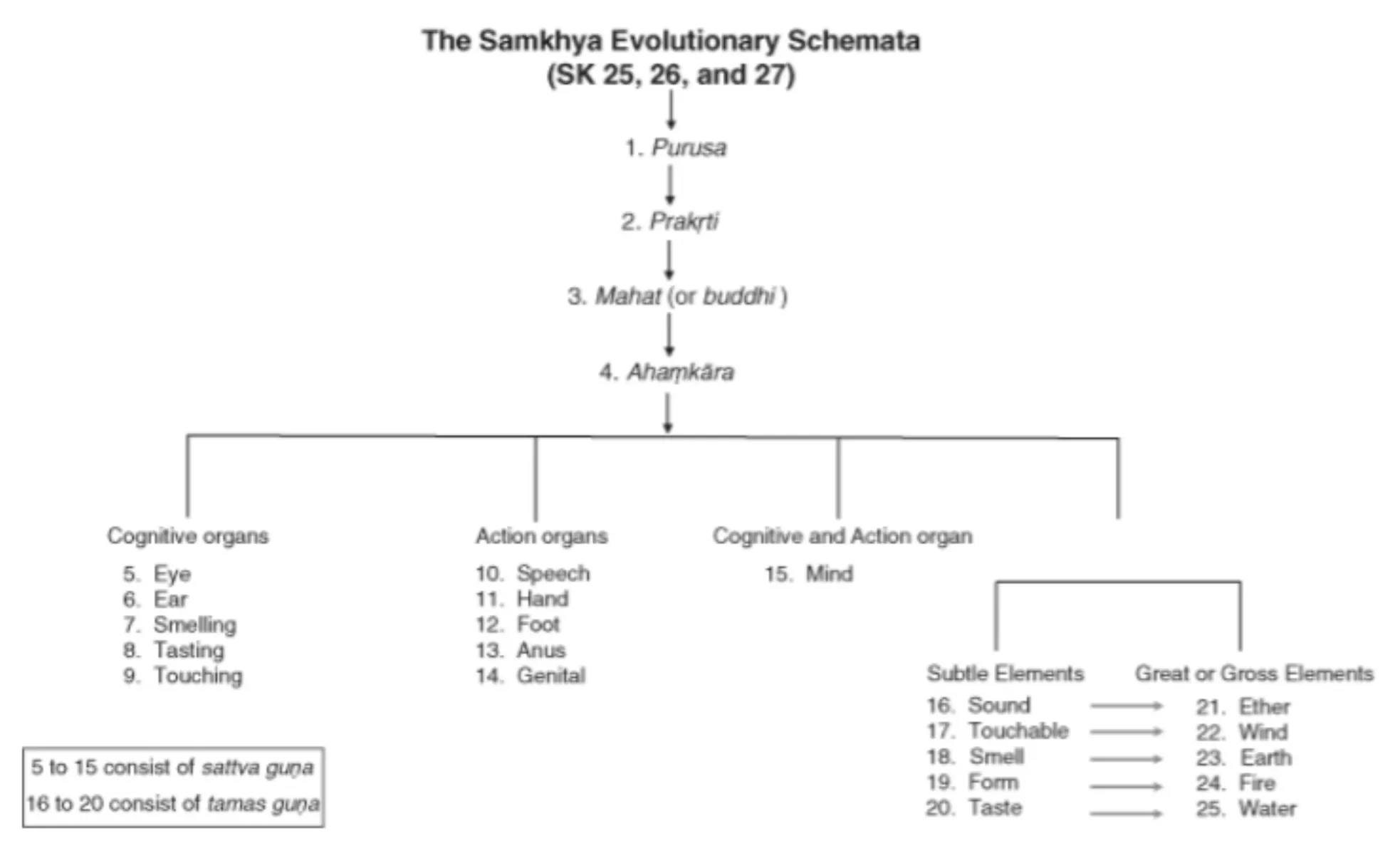

We have the successive causal transformations of the primordial Prakṛti into successive components which is:

Prakṛti => Mahat/Buddhi (the great one - intellect) => Ahaṅkāra (I-ness, ego, first person subjectivity) => Manas (the thinking and perceiving mind) => Jñānendriya (five sense faculties) => Karmendriya (five action faculties) => Tanmātra (five subtle elements of sensation) => Pañcabhūta (five material/gross elements).

I present here a poetic rendering by Grok AI (based on a prose prompt of mine) on how the Sāṅkhya school views the creation of the universe as we know it.

The Dance of Prakṛti: A Sāṅkhya Cosmogenesis

I. The Unmanifest Slumber

In timeless void, where silence reigns supreme,

Prakṛti lies, a latent, boundless dream,

Three guṇas weave her essence, pure and still—

Sattva’s light, Rajas’ fire, Tamas’ will.

Unstirred, unformed, no ripple breaks her rest,

A womb of all, in equilibrium blessed,

Eternal, uncaused, she waits in hush profound,

Till Puruṣa’s gaze ignites her sacred ground.

II. The Stirring Dawn

A whisper stirs, a presence soft and near,

Puruṣa watches, passive yet severe,

No touch, no force, just witness to her play,

Yet balance shifts in Prakṛti’s array.

Rajas awakens, restless, bold, and fleet,

Tamas resists, while Sattva seeks to meet,

The stillness cracks, a tremor starts to sing,

From formless depths, the cosmos takes its wing.

III. Mahat, the Cosmic Mind

Firstborn of change, Mahat unfolds her grace,

The intellect vast, a mirror’s gleaming face,

Sattva shines bright, reflection pure and wide,

A thought divine where wisdom’s seeds reside.

From Prakṛti’s heart, this mind begins to grow,

A boundless sea where knowing starts to flow,

The universe dreams in Mahat’s quiet gleam,

A spark of order in creation’s stream.

IV. Ahamkara, the Ego’s Birth

From Mahat’s depths, a shadow takes its form,

Ahamkara rises, selfhood’s restless storm,

“I am” it cries, dividing unity’s embrace,

Three hues emerge to carve their destined space.

Sattva births mind, serene and inward bent,

Rajas drives action, fierce and turbulent,

Tamas cloaks matter, dense and still to stay,

The ego splits, and worlds begin their play.

V. The Mind and Senses Bloom

From Sattva’s thread, the Manas softly weaves,

A gentle mind that feels and perceives,

Five senses wake—ear, skin, eye, tongue, and nose—

To hear, to touch, to see, to taste, disclose.

Rajas then stirs, five powers bold and free,

Voice, hands, and feet, release, and progeny,

The organs dance, their tasks in motion set,

A living bridge where spirit and form met.

VI. Tanmatras, the Subtle Seeds

Through Tamas’ veil, the subtle seeds arise,

Tanmatras whisper truths beneath disguise,

Sound hums alive, then touch in breezes flows,

Form paints the void, taste waters, scent bestows.

These essences, unseen, yet deep and true,

Hold worlds within, a primal, latent brew,

From ego’s root, they spread their silent might,

The building blocks of matter’s dawning light.

VII. The Gross Elements Unfold

From seeds of subtlety, the gross take hold,

Ether expands, a vast and echoing fold,

Air swirls alive, with motion swift and keen,

Fire blazes forth, a radiant, glowing sheen.

Water then pools, its currents soft and deep,

Earth stands firm, in stillness she does keep,

Five elements rise, the cosmos now arrayed,

Prakṛti’s dance in matter’s form displayed.

VIII. The Cosmos Complete

A tapestry vast, from Prakṛti’s embrace,

The universe spins in time and boundless space,

Mind, senses, elements, in harmony entwined,

A stage is set for souls yet unconfined.

Puruṣa watches, silent, pure, apart,

While Prakṛti plays her selfless, ceaseless art,

Through birth and change, her purpose softly sings—

To free the witness from her fleeting wings.

Prakṛti is like the quantum field or the primordial soup of the early universe—a fundamental, material essence that’s everywhere yet unseen in its raw form. It’s packed with potential, like DNA in a cell, holding the blueprint for everything from stars to human minds. Made of three qualities— lightness, energy, and inertia—it shifts from a dormant state into the world we see, not by choice but by its nature, transforming like water into ice or hydrogen into helium in a star. It’s not aware, but it powers all change, aiming to reveal something beyond itself—consciousness, which the Sāṅkhya calls Puruṣa.

Karma, Moral Agency, Predestination and Epistemological Liberation

We see that Prakṛti, right from the beginning, evolves in a fixed, deterministic manner. This evolution produces the manifest world, including intellects, minds, physical bodies, and gross elements - all governed by the interactions governed by the guṇas. Because this process unfolds mechanistically, without consciousness or intentionality, actions within the realm of Prakṛti appear to be predetermined.

If all effects are latent in Prakṛti, then it sounds like everything in the universe is predestined. Whatever we do and will do are all latent in Prakṛti right from the beginning itself! Then, free will goes out of the picture. But if free will goes out of the picture, then moral responsibility also goes away! If everything I do and I will ever do is already pre-set, then how am I responsible for it? If moral responsibility goes away, where is karma that is so fundamental to Indian thought?! Thus, all human activities - thoughts, decisions, and behaviors, are products of Prakṛti’s components — specifically the intellect (buddhi), ego (ahamkara), and mind (manas). These faculties operate according to the guṇas’ interplay, meaning what we perceive as “choices” are actually determined outcomes of this natural process. The sense of being a free agent — someone who autonomously decides and acts — is an illusion arising from Puruṣa’s mistaken identification with Prakṛti. In reality, Prakṛti is the sole doer, while Puruṣa merely observes. This is definitely a great challenge to the conventional view of karma.

Thus, as the Prakṛti evolves, actions (performed by the body-mind complex) leave saṃskāras (latent impressions) that condition future experiences, such as the circumstances of rebirth. This process is governed by the guṇas and operates mechanically, without requiring free will.

The Sāṅkhya has thus a very different view of moral responsibility. The Puruṣa does not act at all and it is just the observer behind every observable event that unfolds in Prakṛti. The Puruṣa experiences the fruits of those actions (merit for good actions and culpability for bad actions) only because it mistakenly identifies itself with the mind in Prakṛti.

Sāṅkhya explains to us that liberation is nothing but the realization by Puruṣa that it is distinct from Prakṛti and that it is not the doer of actions. This knowledge arises through the intellect’s (buddhi’s) discriminative capacity. But we saw that this intellect itself evolves as a part of Prakṛti’s deterministic process. Once this realization occurs, Puruṣa ceases to identify with Prakṛti’s activities, and the cycle of karma ends for that individual Puruṣa. From the individual’s perspective, having such a realization (leading to liberation) by the intellect may feel like resulting from his own choices of actions and thoughts but it is actually a predestined scripted part of Prakṛti’s unfolding!! All of Prakṛti thus acts for this ultimate realization and liberation of its constituent Puruṣas. The metaphor used in the SK is that the Prakṛti dances for the sake of realization of every Puruṣa!

Liberation in Sāṅkhya is thus the cessation of a misidentification - Puruṣa realizes its true nature as separate from Prakṛti, thus ending its entanglement in the cycle of rebirth and the effects of karma. The key mechanism for this is viveka-khyāti (discriminative knowledge), facilitated by the intellect’s capacity to discern the distinction between Puruṣa and Prakṛti. But this intellectual discernment itself is a part of the processes of Prakṛti which is predestined and latent in it. Thus, the evolution of Prakṛti has a teleological goal (a final purpose) - which is to liberate Puruṣa by making it recognise itself as distinct from Prakṛti.

The deterministic play of Prakṛti, including suffering (duḥkha), thus serves an ultimate purpose: it motivates the pursuit of liberation. In Sāṅkhya, suffering is the impetus for the intellect to seek knowledge. Prakṛti’s evolution indirectly thus leads to Puruṣa’s liberation. Puruṣa does not actively seek this liberation though - he is a passive observer as always; it is inherently free. It has become entangled with Prakṛti due to a misidentification. The process of this realization is also entirely within Prakṛti, which, through its deterministic transformations, ultimately leading the Puruṣa to disentangle itself from this illusion of bondage. Thus, liberation is possible because it is not a product of free will or an alteration of Prakṛti but a cessation of ignorance facilitated by Prakṛti’s own mechanisms. The deterministic system paradoxically enables this outcome by providing the conditions (e.g.a refined intellect) for Puruṣa to recognize its true nature as distinct from Prakṛti. Prakṛti, being unconscious (acetana), hence does not act with deliberate intent. Its teleology is a natural law, like gravity causing objects to fall—it operates mechanically to serve Puruṣa’s ultimate liberation (kaivalya).

To give a crude metaphor, imagine that you are watching a movie involving your favorite hero character in a movie theatre. You have identified yourself emotionally with the hero of the movie so much that you feel happy when he feels happy in the movie and you cry when he cries in the movie because you feel you are actually doing things that the hero is doing in the movie. The theatre is like the Prakṛti. You are the Puruṣa.

You are not responsible for the hero’s actions but still you think so, because you are emotionally so engrossed in the hero of the movie that you experience the hero’s actions and emotions as yours. Liberation is you realizing that you are not actually the hero of the movie and watching it as a distinct dispassionate observer. You had always been different from the hero of the movie all along. You were never responsible for what the hero did or what happened in the movie. But you misidentified yourself with the hero. Now, imagine that the script of the entire movie is such that to make an emotional person like you eventually realize that you are not a part of that movie!! That is what the Sāṅkhya is for you!

Read next part.