# Bodhas

The Intellectual Traditions of the East For Beginners, Part 4 | Bhartṛhari, From Language to Liberation

28 October, 2024

6284 words

share this article

This is Part 4 of a series of articles on Eastern Philosophy. These are the previous parts:

- Part 1: Persistence - Ātman, Brahman & Sat in the Upaniṣads

- Part 2: Pratītyasamutpāda (Dependent Origination) - Buddhist Metaphysics

- Part 3: Classical Schools of Indian Thought - Mīmāṃsā

The individual articles in this series are written so that they are self-contained, but they occasionally may refer to older articles for some details. In this article, we will study a thinker who did not exactly belong to any one of the classical schools, but ended up being influenced by and influencing many of them.

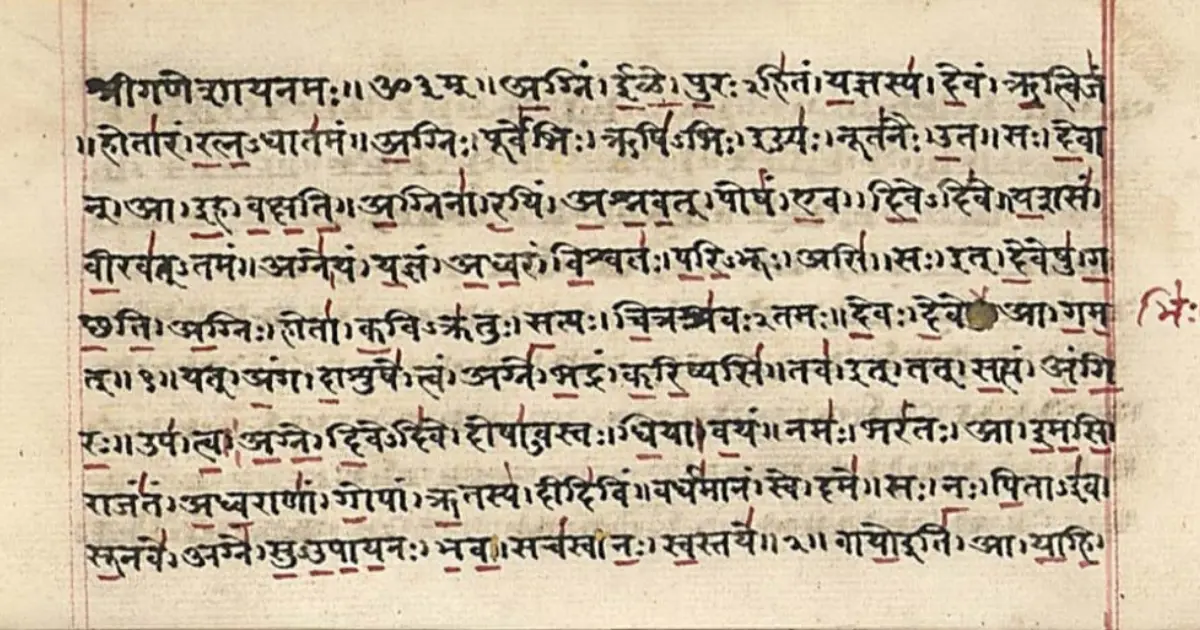

Have you seen people who are so obsessed with their fields that they think their own field is the most important, most fundamental, and the key to understanding and unlocking everything else? Historians are always saying that their field provides the context for everything and that those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it. Mathematicians tell you that their proofs are the highest degree of certainty possible ever in human thought and hence set the benchmark for epistemic truth. And of course, philosophers say that their field is the “queen” of all and every other field is a sub-discipline of it. Physicists say that their equations hold the entire secret to unlocking the behavior of the cosmos. So, you would not be surprised when Bhartṛhari, one of the tallest figures of Saṃskṛta grammar tells us that the study of grammar constitutes the door to liberation!! Though Bhartṛhari gives credit for others for opening up the door (especially Pāṇini and Patāñjali who worked around 5th and 2nd centuries BCE respectively), he was working around the 5th century CE and hence by his time, the Saṃskṛta grammatical tradition was already a millennium old. His famous works are a super-commentary on Patāñjali (called Ṭikā/ Dīpikā) and a master treatise on words and sentences called Vākyapadīya (hereafter abbreviated VP) in sūtra form; and he himself could have authored the commentary to that (called Vṛtti). All the quotations from the VP in this article are taken from the translation by Subramania Iyer (abbreviated as SI).

Bhartṛhari thinks that the analysis of language is the door to liberation. He was from the Hindu tradition and hence believed in the existence of brahman - the single undifferentiated Reality that underlies the entire cosmos (read more in Part 1 of this series) and it is known to us from the Veda. But Bhartṛhari believes that the differentiated reality that we actually see in everyday life (instead of the single undifferentiated brahman) is actually created by language!! Hence, it is language that accounts for the differentiation of brahman. The reason why he would say such a thing directly follows from the way he understands what language is.

Sphoṭa & Pratibhā : Burst and Flash of Knowledge

Do you remember the Kumārila Bhaṭṭa Mīmāṃsā view of knowledge? Wherein words have individual meaning relating to universals and there is a fixed permanent connection between universal classes in the world of universals, and words of language which are manifested as individual objects and individual utterances of words, respectively? And also that the meaning of a sentence is a function of the combination of the meanings of its words (read more in Part 3 of this series). Bhartṛhari differs entirely from this picture.

He says that individual words have not much meaning and are incomplete by themselves, just like how individual sounds have no meaning. For example, the English word “numerology” that we think expresses something is made up of the following individual syllables “nu”, “me”, “ro”, “lo” and “gy” and is made up of the sounds “n”, “u”, “m”, “e”, “r”, “o”, “l”, “g”, “y”.

But do we think that the individual syllables like “nu” and individual sounds like “o” have meaning and that the meaning of the word “numerology” somehow is distributed and split between the individual sounds, so that each of the five syllables “nu”, “me”, “ro”, “lo” and “gy” possesses one-fifth of the meaning of the word “numerology” ? No, right?!!! We don’t get one-fifth of the meaning of the word “numerology” when we hear the first syllable “nu”. The meaning of the word “numerology” comes instantly in a single burst (sphoṭa) of understanding and in a single moment of illumination (pratibhā).

But sometimes, we do find that single syllables and even single alphabets do have meaning. For example, the word “go” in English has only one syllable but yet it has a meaning. The words “I” and “a” in English which refer to myself and the indefinite article, again are made up of just one sound each, but each of those sounds has a meaning in this case. But, would you use these exceptions to say that in general, individual words or syllables have meanings too? No, right?

Those examples of “go” and “I” are exceptions because those are rare cases where the single syllable or single sound forms a word all by itself. In fact, take the word “gold”. Initially, when you would hear only the “go” part of the word, you would think that the speaker has something to do with going right? But only when you hear the full part with the remaining “ld” to hear the complete word “gold”, you realize that what is being talked about is a precious metal and not the motion verb. So, in this case, the meanings of individual syllables or sounds actually misled us and have got nothing to do with the meaning of the complete word. But for some words like “going”, the initial syllable “go” indeed does capture the partial meaning of the full word “going” as the syllable “go” contains the semantic meaning and the syllable “ing” convey a grammatical state of affairs. This again happens sometimes only. Even in the word “numerology”, the part “numero” conveys something to do with numbers (e.g. numeral, numerical etc…) and “logy” has something to do with studies (e.g. biology, zoology, psychology etc..). But again, these are exceptions and may mislead us sometimes and does not change the fact that in general, the meaning of a word is a discrete emergent phenomenon and occurs when the individual sounds and syllables combine, and cannot always be split up and analyzed at the syllabic or phonemic level all the time. The meaning of a sentence is not always a sum of its words like a word’s meaning is not always a sum of all of its constituent parts. Words have a sense and life of their own although sometimes they may look modular, but those modular parts cannot be studied when detached from the word as a whole. As an analogy, in VP, he gives the following metaphor:

Just as the senses, which are possessed with distinct natures and fall upon distinct objects, do not produce their effect without the body, in the same way, all words, getting hold of their distinct meanings, bear no meaning when they are detached from the sentences [in which they occur]

(VP 2.423-424, SI 419-420)

That is, each of our sense organs contribute to our perception in our body; but of themselves, they are of no value, without a body for them to affect. For example, our sight alone by itself, does indeed have some meaning, but cannot be understood in isolation without putting it in relation to the composite perception that is perceived by a perceiver who puts all the data from all the senses together and gets to know something discrete that ultimately cannot be reduced to its constituent perceptual parts. Similarly, that is what Bhartṛhari says for words and sentences. It is a sentence that has a unitary single meaning of its own. There are meanings in individual words and words do contribute to the meaning of the sentences of which they are a part of. But the sentence is a unitary idea and the meaning of a word is not always indicative of the meaning it actually takes in the sentence. The sense of a word cannot be fully understood unless the full sentence (of which it is a part of) is known. The cases where we feel words have meanings and that they contribute to the meaning of the sentence is like those special cases where in individual syllables contribute partially to the meanings of words, says Bhartṛhari. Also, the meaning of individual words may also mislead us while understanding the meaning of a sentence, he says. He gives lots of justifications and arguments. Two of them are given below:

1. Simultaneity

The first argument is that when we speak a sentence, the sound of the first word disappears by the time the last word is sounded. Individual words of a sentence pass away when they are uttered. So, by the time we listen to the last word, the sound of the first word has disappeared.

Note: In fact, when we listen and speak, we do not pause between each and every word at all and the entire sentence flows seamlessly from one word to another as easily as it flows from one syllable to another. In fact, this is more true in ancient Indian culture where language was still primarily understood as something spoken and not as something written. Nowadays, we are so used to seeing language written on the page and while writing, we leave spaces between every word. In fact, when a person has learnt to read and write in a foreign language and proceeds to develop listening comprehension, one of the most difficult things that he faces while listening to native speech is developing an intuition for figuring out where one word ends and another begins - how to split words (padaccheda) in flowing speech.

In fact, even in Western writing, the practice of leaving spaces between words is a fairly medieval one. Ancient manuscripts and inscriptions in the Western world do not leave spaces between words to conserve space (writing materials were costly in the ancient world). Also, most written texts in the ancient world were meant to be read out loud and hence, people read these texts out loud and let their auditory intuition of the language do the splitting of individual words. Only post the Carolingian Renaissance after the 8th century, was the practice of leaving spaces between words developed in Europe.

In fact, even today, in Saṃskṛta, there is no spacing between words shown in writing if there is a sandhi possible. Spacing between two words X and Y are shown only if X ends in a vowel and Y begins with a consonant - otherwise, the writing continues without leaving any space. For example, the sentence “I give that” is written in Saṃskṛta as “तद्ददाम्यहम्” which is literally “taddadāmyaham” where the word boundaries are “tad|dadāmy|aham”. Identifying the individual words and undoing the sandhi is still the most difficult part for a student while learning Saṃskṛta because he is used to reading and does not hear the language much and hence has to have a very high proficiency in the language to parse words in flowing speech. In fact, consider a person who is totally illiterate and to whom, language means only speech. Then, will the concept of a word even make sense? When you learnt your first language as an infant while lying on your mother’s lap, did you learn word by word? All you heard were lots of sentences and your mind learnt to produce the appropriate speech by observation. In fact, can a native but illiterate English speaker know that the utterance “can’t” actually splits into two words as “can + not”, unless she learns grammar? No! So, Bhartṛhari says that while words sometimes do convey some sense, they are hardly sounded in isolation, and they are not sounded simultaneously in time and are produce one after the other.

2. Mislead

For example, consider the sentence “There is not any cow in my room”. The word “cow” would make you think that the sentence is about cows in the state of affairs, but actually the sentence does not talk about any cow, because of the negation “not”. According to him, only the entire sentence “There is not any cow in my room” has a single idea or a burst of meaning which is a single message to be conveyed - the message that there are no cows in my room. All the sounds, syllables, and words contribute in making up the message, the meaning of the individual words contribute to the message conveyed by the sentence but the meaning of the message is understood in a single flash (pratibhā) of understanding and is conceived of as a single burst (sphoṭa) of thought.

Thus, according to Bhartṛhari, the basic unit of language is a sentence which is unitary in a formal sense (as signifier) and semantically (as meaning) even though it is physically articulated as a temporal sequence of phonemes, syllables or words. Isolated words have no meaning unless they form a sentence with one word. People always speak in sentences. People do not dissect sentences into words while listening nor do they speak word after word while speaking. Words, roots, prefixes, suffixes, and phonemes are just a grammarian’s analytical tool to probe, describe and analyze a language - they are all theoretical constructs that play no role in the actual process of communication.

How Language Affects Cognition & Perception

Do you remember from the previous article on Mīmāṃsā (Part 3) where in there was a distinction between indeterminate perception and determinate perception? Presenting it again here for ease:

Indeterminate perception (nirvikalpa) is that raw perception at the first moment of association between senses and the sense object, had by infants, where there are no categories or differentials imposed on the perceptual stream. On the other hand, determinate perception (savikalpa) is when we objectify this perception and categorize them into object classes and particular objects with certain qualities that are situated in space and time.

What does Bhartṛhari have to say on this distinction? He says that there is no such thing as a purely indeterminate perception (nirvikalpa) - pure perception without the imposition of various limiting criteria (upādhis - like universals of object classes, quality, space, time, etc…). The VP says that things can never be known as they are by themselves, independent of the mind. For example, in VP 3.14.474:

The nature of things in isolation is not ascertained; no verbal expression refers to them when their natures have no (mental) representation.

So, language just gives words to express these concepts that arise in all perceptions. The fact that I see a separate persisting object that has four legs and a seat in my room is inherent to my perceptions itself. Language just gives a word like “chair” to express it. Also, even if I see only the front part of a pot, I immediately become aware of the full pot and categorize it as a distinct object belonging to the universal category “pot”. All of us would agree that if we see only the front side of a pot from a point of view, we would actually always feel that there is actually a full pot with a backside - we would be surprised to find out that if the pot whose front side we saw is actually a hologram without any back side. So, in some sense, we actually perceive the full “pot” even though we receive sense data regarding only one side of it. So, the mind arranges sense data according to these notions and categories like “pot” based on previous perceptions and the situation and what pots are used for - all of this is inherent to our perception and is expressed in communication by language. To quote in his own words (VP 2.156, SI 161):

In ordinary experience, it is difficult for anyone to perceive all the parts [of an object]; the entire object is inferred by means of (those) parts that are perceived.

This happens through recollections from previous perceptions of pots that we had. So, in some sense, perception by itself has an inferential component to it. So, there is no such thing as pure perception or unalloyed pratyakṣa without any objectification and analysis. That is, Bhartṛhari says that every perception has within it - some sort of inference and analogy. So, one cannot really separate the various sources and means (pramāṇa) of knowledge very rigidly. Regarding the issue of perception of infants being undifferentiated, which was raised by the Mīmāṃsā school, Bhartṛhari says that even the most rudimentary perception in infants, there is in it, what he calls a “latent seed (bīja)” of language which grows into full blown cognition as the infant grows to express full blown language. That is, every infant has within him or her a latent ability to carry out this objectified perception and as the infant grows up and develops more exposure and knowledge of a language, this latent seed is realized fully. Any perception is always objectified and hence is linguistic and permeated by words - we can only grasp what we perceive by filling them under certain descriptions or concepts, and language just puts these descriptions and concepts into vocal expressions (VP 1.131, SI 115).

In ordinary experience, there is no cognition that does not conform to language. All knowledge appears as if it were transfixed by knowledge.

Hence, Bhartṛhari’s view is that one does not know the world (as it is), independent of our transcendental categories of the perception that comes with it in our mind. Bhartṛhari just says that language is a verbal expression and a meditator of these transcendental categories of perception.

Upalipsā & Vivakṣā: Perception by Intention

Bhartṛhari also gives another justification as to why our perceptions are always composite and mediated by a complex subjective processes. He says that even our most rudimentary facts of perception can never be truly objective and are in fact subjective - a construction of our minds. He says that things that we perceive as actions and express it through verbs in language, are not actually perceived. Consider for example, a simple sentence that “Devadatta is cooking rice in the pot with firewood”. What we actually see are various sequences of events - we see Devadatta moving around in the kitchen, then lighting the firewood, boiling the rice which turns soft and edible. All these are directly seen in stages. While each of the factors (sādhanas) involved in this action are seen stage by stage, the sentence “Devadatta is cooking rice in the pot with firewood” is actually a result of the synthesis of all these perceived events that links together, all of these momentarily observed perceptions. It is the speaker that puts together all these raw events that he has seen and provides a composite description such as “Devadatta is cooking rice in the pot with firewood”. So, what actually look like as an objective matter of fact - that Devadatta is cooking rice with firewood - according to Bhartṛhari, is actually a highly subjective account of what is seen. Thus, after perceiving various objects in various positions at various times and undergoing various transformations, what we call as a particular action like “cooking” is not an objectively direct percept but is actually a mental construct, that is created in our own minds which assemble all these series of events together according to the needs and circumstances. When we observe the rice being boiled, we no longer see the lighting of the firewood or the raw rice being put in the pot - those are all events of the past; yet our mind puts them all together to create a composite construct called “cooking”. For example, VP 3.8.7-9:

The natures of those complex [of events] which both exist and do not exist* because [they happen] in a sequence, do not have [a direct] relation with sight etc., whose objects are real things.

I.e. In a process (like cooking), what exists at any given time is non-existent in any time before it or after it but our mind synthesizes all these events happening at various times and understands it as a single process (like cooking).

Also, another important thing is the fact that all these perceived events that I have seen through my eyes constitute an action called “cooking” is actually not objective but depends on our interest and intention in this situation - if there were an alien who observes this same sequence of events, he will put this completely differently. It is our subjective cultural constructs that categorize a certain sequence of events done for certain purposes as cooking. Even the same subject, while perceiving the same sequence of events at a different time or place or situation, might put it differently. To put in his own words (VP 2.136):

Perception varies even with regard to a single perceivable object. Even the same (individual) sees it differently [when perceiving the same event] again at different times.

Previous experiences, cultural presuppositions, contingent needs, expectations, and so on, all (these) affect the way we perceive things (VP 2.296):

That which is seen variously according to differences of space, time and [conditions of] the senses, is determined [by the intellect] according to the common understanding of people.

Thus, even the simplest of our perceptions that we put in words - are actually subjective and are shaped by our particular intention (upalipsā) to view in a certain way which leads to a linguistic desire to put it in speech in one particular way (vivakṣā) which we actually do put it through actual sounds. Thus, the fact that we subjectively choose to verbally express a particular set of events using a particular choice of words comes from an underlying fact that we actually subjectively choose to perceive a particular set of events using a particular choice of viewpoint that is shaped by our intention at that moment. That is, perception itself is shaped subjectively by the intention of the subject which includes among other things most importantly - focusing on those aspects of the environment that are relevant to the subject at the time of cognition. For e.g., when I observe Devadatta cooking rice while sitting from an chair, I choose to ignore the pressure due to contact that the chair exerts on my body or choose to ignore a crow that is flying at a distance even though I can feel the pressure and hear the crow’s sound.

This stress of the volitional component of perception is expressed in several places explicitly in the VP. For example in VP 2.404, SI 400:

Just as sight leads to seeing once [it is] aimed (Saṃskṛta: praṇihita) [towards a particular object], similarly a word becomes expressive of a meaning (when) used (Saṃskṛta: abhisaṃhita) intentionally (Saṃskṛta: saṅkalpena).

In the Vṛtti (commentary), we have:

In this respect, just as sight, when it has the abilities (required) to (apprehend) the contents of the perception of all perceivable (things), performs the perception of this or that (thing) on which it is intentionally directed, in the same way even a word, which is able to convey several meanings, embraces the (particular) meaning for which it is used—(i.e.,) it makes [that meaning] merge (Saṃskṛta: sanniveśayati) in itself, it reveals [that meaning].

Liminal Perception & The Seed (Bīja) of Language

Bhartṛhari’s account seems to kind of disorient us - it looks like our ordinary workaday cognitions which we express through language is so selective and so discriminating and depends on the unifying and analytical power of the mind! What Bhartṛhari says is that what we actually perceive is a selective choice and a selective manner of categorizing what we actually receive from the senses. The selection and the manner of categorization is shaped by our mind, our intention, interests and cultural assumptions. But Bhartṛhari has no choice to do it if he gives primacy to language. This is because if we describe what we perceive using language, a language being finite can convey only finite information whereas a perception has infinite amount of information that can be conveyed. So, if we want what is expressed through language to be equal to what is perceived, then this selection is necessary. Bhartṛhari says that our actual perception itself is indeed what is selected and digested in our minds. But there are several problems when we agree with this viewpoint.

- Did you remember the last article (Part 3) where we happily defined perception (pratyakṣa) as the contact between sense organ and sense object? If this indeed is defined as perception, there has to be some room for indeterminate perception that is passive, non-selective, non-categorizing and simply just receives the impressions that are coming from outside. Isn’t it?

- Sometimes, we may not actually be aware of a particular thing X, at the moment of perception because our focus and intention was on something else but later, we can recollect that thing if the later situation demands it. But according to what Bhartṛhari seems to be saying so far, perception indeed is what we get after we finally choose (upalipsā) and discriminate. So by that logic, we should admit that we did not perceive X at that time of its impression. Then, how did we infer it later? (Such a perception which we are not aware of at that moment but can recollect later are called liminal perceptions).

- Most of us would intuitively think that even those things that we never focused our attention on or did not categorize at the moment of its perception still exists somewhere at the corner of our mind to be recollected later.

Bhartṛhari kind of admits that there are cognitions that are latent and devoid of objectification because the intention of perception were not shaped towards them at the time of perception. But he insists that even such an inchoate mental state of impression of which the subject is not aware of at the time of perception, is inherently infused with language because even if we recollect it later due to a trigger, we express it objectively and in terms of categories that are then expressed by language. He calls it as avikalpa jñāna (unintentional cognition). How does this differ from the nirvikalpa jñāna (indeterminate perception) defined in the previous part, which is cognition without any expressions and categorizations? The difference is that while the nirvikalpa jñāna (indeterminate perception) is devoid of any categorical constructs, the avikalpa jñāna (unintentional cognition) is still determinate only with all sorts of categorizations (in whose terms it is later recollected when triggered) but just that the subject is not aware of it as he has not intended his aim towards that avikalpa jñāna (unintentional cognition). So, all cognition is determinate, conceptualizing and categorizing only - which are all expressed verbally through language. What differs is whether we are aware of them or not. Bhartṛhari clarifies this right in the beginning section of this VP and hence he must have been aware that this was an important issue to be clarified. It is given below in the commentary to VP 1.131, SI 115:

In the same way as one’s disposition [to speech] is in a withdrawn form, similarly a cognition devoid of conceptualization (avikalpena) does not produce any effect, even though it has arisen in relation to cognizable objects. To illustrate: even though a cognition occurs in a man who is walking in a hurry because he touches upon grass, lumps of earth, etc., [in him] there is just a sort of cognitive state in which, as the seed of the disposition to speech is close at hand, once the powers, confined to given meanings, of the verbal expressions that grasp the (perceived) objects and whose form can be conveyed have manifested, the reality being apprehended — shaped by knowledge infused with language, [i.e., by knowledge] falling under the power of language—conforms to (such) knowledge, appears with a distinct form (and) is expressed by [the awareness] “I know X.” And when the seeds of speech have manifested themselves because of other conditions, this (reality) becomes the cause of recollection. Thus, according to some teachers the continuity in the operation of knowledge is similar to [what it is in] the mode of wakefulness even when one is asleep. But in that state (i.e., sleep) the seeds of the disposition to speech only operate in a subtle manner.

He uses this same word “seed (bīja)” to justify the perception of infants too which was alluded to in the beginning of this article. To quote another extract from VP 1.132, SI 116:

If knowledge ceased to have the perennial nature of language, the light [of consciousness] would not shine for that (nature) makes reflective awareness possible.

The commentary for this reads:

Even in a state of unconsciousness there is a subtle conformity [of knowledge] to the nature of language. The light [of knowledge] that initially falls upon external things reveals their mere nature of objects (vastu-svarūpa-mātram) without seizing the causes [of their manifestation] in a manner that cannot be expressed (avyapadeśya) as ‘This is X’.

So, according to Bhartṛhari, the perception of infants and the perceptions of which one is not explicitly aware about at the moment of perception - both are inherently categorizing and linguistic as well - there is the seed of linguistic expression there as well - just that it has not explicitly been realized. So, the perceptions of infants and the perceptions of adults regarding that of impressions that are not realized by the subject at the moment of perception - both of them are not perceptions without conceptualizations but they are perceptions with conceptualizations whose awareness has not yet been generated in the subject due to lack of intention. So, linguistic dissection of perception is there in the subject not just when he is engaged actively towards the apprehension but even in the latent states where the subject is not explicitly aware of the intentions of that which he perceives. The seed of language is thus there in unaware cognitions, the cognitions of infants and even that of animals!

For e.g., in VP 1.134, SI 118:

This [nature of speech] (vāgrūpatā) is the cognition (saṃjñā) of all beings undergoing rebirth; it exists internally and externally. The consciousness of any kind of creature does not transcend that mere [nature of language].

The commentary for this:

In ordinary experience, people call (something) sentient or insentient because of that which conforms [or does not conform] to the nature of language in consciousness.

So, all knowledge corresponds to and is inherently linguistic.

The Brahman and Language

How does Bhartṛhari build an ontology out of language and situates the Brahman there? He believes (part 1 link) that there is a continuous stream of consciousness that runs across all perceptions of the subject that is linguistically expressed as “I am” (irrespective of whether we intend and focus towards it or not). But if Bhartṛhari says that language is the fundamental nature of reality, how does it relate to liberation and where does Brahman fit in here in the world of linguistic concepts?

Do you remember last time (Part 3) when we saw that the meaning of any word always refers to a universal - a class or a type - the word “chair” does not refer to a particular chair but to a class of objects that have the structure of a “chair”. This universal meaning is what enables us to call different chairs all around by the same word “chair”. Like the Mīmāṃsā school, Bhartṛhari also believes in the eternality of the Veda which implies that there is a primordial world of universals (that classify reality), having a fixed relation to the primordial world of words. It is these that are used in the Veda. These manifest in reality as particulars of the universal and as particular utterances of words respectively. For example, the various particular chairs that we see are earthly manifestations of the universal idea of “chair”. A particular person pronouncing the word “chair” is an earthly manifestation of the word “chair”. Unlike in Mīmāṃsā though, the various universals are not intrinsic to the perceptual world itself, but they are also not something that the mind imposes upon the perception (like in Kant). Bhartṛhari is more like Plato in this sense - he considers these universals and language to be a more fundamental part of reality - different from this mundane material world but illuminates it and is the source by which it is perceived and understood.

But, Bhartṛhari also believed in the Brahman-Sat, the single source of undifferentiated Being that underlies all of the cosmos and also the source for everything. Where does the Brahman fit in here? Let us hear it from the man himself who says in the very second verse of the text1.

Who has been taught as the One appearing as many due to the multiplicity of his powers, who, though not different from his powers, seems to be so.

(VP 1.2)

The commentary for this:

Appearing as many, the powers which are mutually opposed and are identical with Brahman accumulate in it which is essentially the Word. In a cognition in which many objects figure, the different objects which figure such as earth, people, etc., do not affect the unity of the cognition. There is no contradiction between the multiplicity of the things like trees which are cognised and the unity of the cognition [of tree-ness]. The form of the cognition does not really differ from that of the object, because different forms of the objects are not beyond the unity of the cognitions [of the form]. Similarly, the powers which appear to be different from one another are not really so. The text ‘though not different from his powers’ means: the powers are not different from Brahman as the universal and the particular are from each other. But it appears to be different when it assumes the form of the different objects which figure in it.

So, do you see what is happening here? What is being said here is that as the multiple trees are related to the universal of the “tree” because they share the essence of “tree”, so are the multiplicity of forms that we see or talk about in language, are related to the Brahman. So, the universals are all emanating from the brahman as all particulars emanate from a given universal. Or to put in other words:

Just as the universals divide Brahman while being identical with it, so do individual giraffes both divide and yet are somehow identical with the universal “giraffe”.

The various individual giraffes are separate from each other and from the universal idea of “giraffe”. But, they are also identical with the universal idea of “giraffe” (which is why we use the same word ‘giraffe’ to describe all of them) and the universal “giraffe” is the source of all the particular giraffe and enable us to make sense of those giraffes. Similarly, the various universals themselves, are both identical to the Brahman and also divide the Brahman and are sourced from it.

In some sense, Brahman is the highest universal. It has as its defining characteristic or form - just Being. All universals emanate from this Brahman and divide it. And all particulars emanate from a universal while dividing it.

So, we see that universals are intermediate between the single brahman and this world of multiplicity by specific objects.

But we have a problem of interpreting Bhartṛhari here. To revel in the individuality of the trees can be seen as to prevent the recognition of the common unity of tree-ness in all of them. So, do linguistic universals themselves which divide Brahman actually prevent us from recognizing the unity of Brahman? From this point of view, language would be an illusion that prevents us from realizing the unity of Brahman. So, in this point of view, the multiplicative reality encoded by language is actually an illusion (māyā) and a ladder that has to be thrown out once we are liberated. This is an advaitic (non dualistic) interpretation of Bhartṛhari. This interpretation of Bhartṛhari brings him closer to his contemporary Buddhists and the later Ādiśaṅkarācārya both of whom outrightly condemned or would condemn the pluralistic world of experience as an illusion. In this point of view, language is an obstacle because it distorts the only reality (Brahman) by pulling it apart into an infinity of parts. But there is also another way of interpreting Bhartṛhari wherein the linguistic universals are not seen as unreal and illusory but as a secondary reality or as a manifested reality of Brahman.

Bhartṛhari has passages that allude to both non-dualism and dualism and quite a bit of his metaphors are ambiguous and can be interpreted either way. I do not want you to bore you with quotations and my own thoughts. You should read the Vākyapadīya and conclude for yourself while deciding what he must have had in his mind originally. You can read the book in translation by SI here.

Read next part in the series - The Intellectual Traditions of the East For Beginners, Part 5 | Buddhist Metaphysics from the Theravāda Sūtras