# Bodhas

The Intellectual Traditions of the East For Beginners, Part 5 | Buddhist Process Metaphysics from the Theravāda Sūtras

2 November, 2024

4670 words

share this article

NOTE: This is Part 5 of a series of articles on Eastern Philosophy. The previous parts of the series can be accessed here:

- Part 1 - Persistence - Ātman, Brahman & Sat in the Upaniṣads

- Part 2 - Pratītyasamutpāda (Dependent Origination) - Buddhist Metaphysics

- Part 3 - Classical Schools of Indian Thought - Mīmāṃsā

- Part 4 - Bhartṛhari, From Language to Liberation

The individual articles in this series are written so that they are self contained but occasionally may refer to older articles for some details.

In the previous two articles, we began the study of Indian philosophy in the era of sūtras and darśanas. We began with the ritualistic school of Mīmāṃsā and then went on to study a philosophy based on language by the grammarian Bhartṛhari. As I had remarked, in this era, there were lots of schools within the Hindu, Buddhist, Jain, and other folds, vigorously debating amongst each other, such that we can really not understand the work of a particular school without an awareness of what the other schools did. All of these schools were arguing, challenging, responding and building up on each other. Hence, I think it is wise to explore Hindu, Buddhist and Jain schools in a mixed manner, rather than sequentially to understand and appreciate the interactions and challenges that all schools posed to and were posed by the others. Hence, before continuing further, it is wise to begin where we left in a previous article on Buddhism, by catching up on the history of Buddhism after the death of the Buddha, up to the era that we are interested in for the current discussion. After that, we will explore selections from the Pali Theravāda canon of Buddhist scriptures and the philosophy that it represents.

The Historical Development of Buddhism: The Pali Tradition

The Buddha himself lived in approximately the 6th or 5th centuries BCE. He didn’t actually write anything down himself. He taught orally like all other gurus of his day, gathered disciples, and established the community of monks named Saṅgha. After he died, he did not appoint a successor and wanted the institution of the Saṅgha to continue based on the path of the dharma and the monastic rules (vinaya) that he had preached and established. For a few centuries after his death, the community of monks in the Saṅgha transmitted his teachings through oral memorization. But, problems began to emerge soon after his passing away. For example, the Buddha before his death had told Ānanda, one of his chief disciples that the minor rules for monks could be abrogated after his death; but because he did not clearly specify what rules were minor and what were major, the Saṅgha was hesitant to eliminate any of them. The monks in the Saṅgha would be mendicant preachers who would meet together for three months during the rainy season (when travel was difficult) in what was called as a council. In these meetings, they would recite the rules of the vinaya and his teachings. At this first council that was convened just after his death, his disciple Ānanda is said to have recited all the sayings of the Buddha, which he had perfectly memorized. Another of Buddha’s disciples Upāli is said to have recited the monastic rules of the vinaya, which he had memorized. Upāli had been a barber before joining the Saṅgha and since he also knew the monastic rules, his skills came in handy and he would shave newly initiated monks into the Saṅgha. The oral transmission of Buddha’s teachings continued for several centuries and due to the spread of Buddhism over large areas, divergent interpretations of Budda’s teachings emerged - it is said that there were 18 different schools each with a different set of memorized teachings. Eventually, when the dust had settled, only one survived and had its teachings written down in writing. This school is called the Theravāda (Saṃskṛta: Sthavira) school (meaning: way of the elders). Its texts were written down in Sri Lanka in the year 29 B.C.E, under the sponsorship of the king there who convened the community of monks who then employed 500 scribes to write everything down. The language in which the texts of the Theravāda canon are preserved is Pali, a Prakrit that was very loosely based on the dialect in which the Buddha would have spoken. Hence, this school is also called the Pali school.

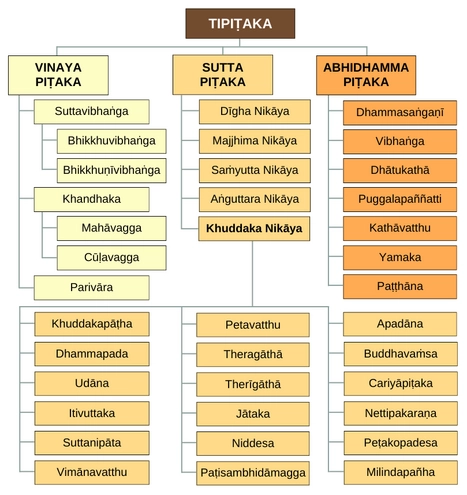

The canon of Pali texts are the oldest surviving texts of Buddhism and all that we know about the Buddha come from these texts. Its canon of texts are divided into three parts or three baskets (Pali: Tipiṭaka). The first basket consists of seven books of vinaya, the rules for the monks and nuns. The second basket consists of five books (nikāyas) collectively called suttas (Saṃskṛta: sūtra) which are the collections of sayings of the Buddha. The third basket is called the abhidhamma (Saṃskṛta: abhidharma) which consists of philosophical expositions developed based on the Buddha’s teachings. The canon is summarized in the image below.

Some famous texts in the Sutta section that are a must reading for everyone are the Dhammapada, the Theragāthā (verses of the Elder Monks), the Therīgāthā (verses of the Elder Nuns) and for the children, the tales of the previous lives of the Buddha - Jātaka. Over the centuries, beginning in India and later augmented by Sri Lankan monks, bodies of commentaries began to build up in Pali and Old Sinhalese. In the fifth century C.E, Buddhagosa compiled all these commentaries and translated them into Pali. He also wrote works like Visuddhimagga and other commentaries. Another southern Indian monk named Dhammapāla, also wrote further volumes of Pali commentaries in the sixth century C.E.

Since this Pali canon by itself is huge (ignoring the later volume of commentaries in Pali and Old Sinhalese!) - especially the Abhidhamma basket - sometime between the 8th and 12th century, a Srilankan monk named Ācariya Anuruddha wrote a manual named Abhidhammattha-saṅgaha (Saṃskṛta: Abhidharmārtha-saṅgraha) that summarizes and provides a comprehensive exposition to initiate a novice into the study of the Abhidhamma texts - and has ever since been used for that purpose. The Theravāda school spread to Sri Lanka, Burma and Southeast Asia.

In the Theravāda school, the Buddha is considered as a human role model to be emulated and enlightenment can be attained by following his path. But this can only be done by monks and nuns who have the time and the conducive atmosphere to put the effort to attain enlightenment in the present birth itself. The laity would materially support the monks and nuns and earn good karma so that they would be reborn in another birth in good conditions that would make them suitable to adopt the monkish way of life for attaining enlightenment.

The Historical Development of Buddhism: The Saṃskṛta Tradition

Having talked about the Theravāda school, let us now go back in time. In about the first centuries B.C.E, which is four or five centuries after the death of the Buddha, a new group of anonymously written Buddhist sūtras of relatively mysterious origins began circulating in India which offered a different view of the Buddha and Buddhism. These texts were not in Pali but in Saṃskṛta, the classical language of Hinduism. Some monks began to accept these teachings but for a long time, it was a minority movement. In these texts, the Buddha was not merely seen as a great man who found the path to enlightenment but he became a god to whom one could pray to and worship to. There arose the concept of a Bodhisattva - a being who attained enlightenment but out of compassion, did not go to nirvāṇa but stayed on in the universe until all souls would be freed from saṃsāra. In this path, enlightenment in this life could be accessible to everyone - not just monks. This was possible due to the compassion of the Bodhisattvas. Hence the schools of Buddhism based on these texts came to be known as Mahāyāna (Saṃskṛta: Greater Vehicle) Buddhism - the vehicle that can carry a greater number of peoples across the ocean of saṃsāra. The sūtras were longer, and the miracle stories regarding the Buddha were even more grandiose. How could these newer sūtras claim to be authoritative?! Its followers claimed that these teachings were the higher secret teachings of the Buddha given to his innermost group of disciples while the ordinary monks got the Theravāda teachings. The secret teachings were claimed to be hidden (in caves or heavens or underwater palaces - depending on the text!) for centuries till the present age when they could be revealed. It was claimed that while the ordinary teachings were heard and preserved by the disciple Ānanda, these secret higher teachings were heard and preserved by celestial beings and Bodhisattvas who were revealing that again. For example, the Chapter 2 of the Lotus Sūtra tells us that just when the Buddha was about to teach this higher dharma, all his earthly followers got up and left because they were unable to comprehend his words. The teachings were instead heard by the heavenly beings or the Bodhisattvas who remembered and preserved these teachings in a line of supernatural transmission! The Buddha in some of these texts is said to have achieved enlightenment eons ago, but due to infinite compassion, he incarnated as a prince in the sixth century BCE and pretended to be in illusion, and finally pretended to have achieved enlightenment for the first time for the sake of benefit of others.

The Buddha is described to have three bodies (trikāyas) in these texts - the earthly body as Prince Siddhārtha, the heavenly body of enjoyment in pure land (we will see about this in the series on East Asian Buddhism) and finally the dharma body which is the unmanifested limitless body which was his essence and corresponded to the supreme state of absolute knowledge. Not all monks accepted these new teachings and the claims. Some even outspokenly criticized that these Mahāyānas were arrogant to declare their own poetic creations as the words of the Buddha. Still over time, these gained acceptance and the collection of texts accumulated and the movement spread. In the end of the first century CE, these Mahāyāna Buddhist monks began to travel to China taking along with them these new Saṃskṛta texts and also some Pali texts. Eventually, over the course of the next 800 years, many of these Saṃskṛta and some Pali texts got translated into Chinese - with Buddhist missionaries traveling back and forth between India and China, to keep up with newer texts emerging in India that could be translated into Chinese. Along with original Buddhist texts written in Chinese in the first millennium, eventually around the 10th century C.E, the collection of Chinese Buddhist texts stabilized into a canon which was much larger than the Theravāda canon. It was published as soon as the printing press was invented. The Chinese canon also includes Chinese translations of five versions of the Vinaya (monastic rules) from schools other than the Theravada, a version of its Abhidharma, many Mahayana sutras, Tantras (esoteric texts), commentaries, treatises, encyclopedias, dictionaries, histories, and even some non-Buddhist texts from Hinduism. From China, Mahāyāna Buddhism would travel to the countries influenced by it - Japan, Vietnam, Korea etc. Many sub-schools of Mahāyāna Buddhism would develop in China, Korea and Japan about which we will see in the history and philosophies of East Asia in this series. One such famous sub-school that has become popular in the West recently is the Zen Buddhism of Japan. The word Zen is actually derived from the Pali word jhāna which in turn is derived from the Saṃskṛta word dhyāna meaning meditation.

Then, much later in the 7th to the 13th centuries, Buddhism reached from India to Tibet and there were translations of Buddhist texts into Tibetan, and finally, a separate Tibetan canon was established in the 14th century, with two major divisions: the Kangyur, which consists of texts attributed to the Buddha and translated from Saṃskṛta originals (98 volumes), and the Tengyur, 224 volumes of commentaries and treatises. The subbranch of Mahāyāna Buddhism in Tibet then developed to define itself separately and is called the Vajrayāna Buddhism. This sect of Buddhism is represented by the Dalai Lama.

Most of the texts in the Tibetan canon were translated from Saṃskṛta. The original Saṃskṛta texts did not close themselves into a canon in India and remained open. We often have Chinese and/or Tibetan translations of Buddhist scriptures for which the Saṃskṛta originals no longer survive. Buddhism has the most extensive canon among all world religions and not even monks read all the texts!

It is the Mahāyāna tradition that interacted with the Hindu schools the most in the era of darśanas and hence we will focus on it in the main narrative. The Mahāyāna tradition diverged into three major schools based on divergent interpretations and commentaries on the sūtras. They are:

- Abhidharma (Vaibhāṣika & Sautrāntika)

- Mādhyamaka

- Yogācāra

We will see this in detail in future articles. In the remainder of this article, we will explore the underlying basic philosophy in the Theravāda texts.

Substance vs Process Metaphysics

Actually, whatever philosophical content that we saw in the second article on Buddhism (part 2 link here) are taken from the Theravāda canon only; and hence, we had already begun exploring it there. Here, let us elaborate and solidify that. The central idea in Buddhism is what is called by philosophers as process metaphysics. Hinduism and Western philosophy are both dominated by a contrastive picture which philosophers call as substance metaphysics. Let us first learn about these two words.

All that we perceive, in every moment, has both elements of change and elements of constancy to it. Of course, everyone agrees that our observed world is changing every moment in all sorts of ways. But we also agree that there are some constant enduring entities in the world. For example, imagine a ball that is kicked by a person. Its position is changing at all times. But at each instant of time, you feel that it is the same ball out there. You see the ball at one position at one time and at another position at another time. But somehow you feel that the ball that you saw at the first instant and the ball that you saw at the second instant and the ball that you saw at all intervening instants is the same ball. You think of the ball as a single unitary substance that endures through time. Also you think of the ball as an independent entity whose existence does not depend on any other entity or depend on whether someone is looking at it or not. Our perceptions are always cognized in terms of various types of enduring independent substances with various types of abstract properties - balls, bats, dogs, sand, etc.

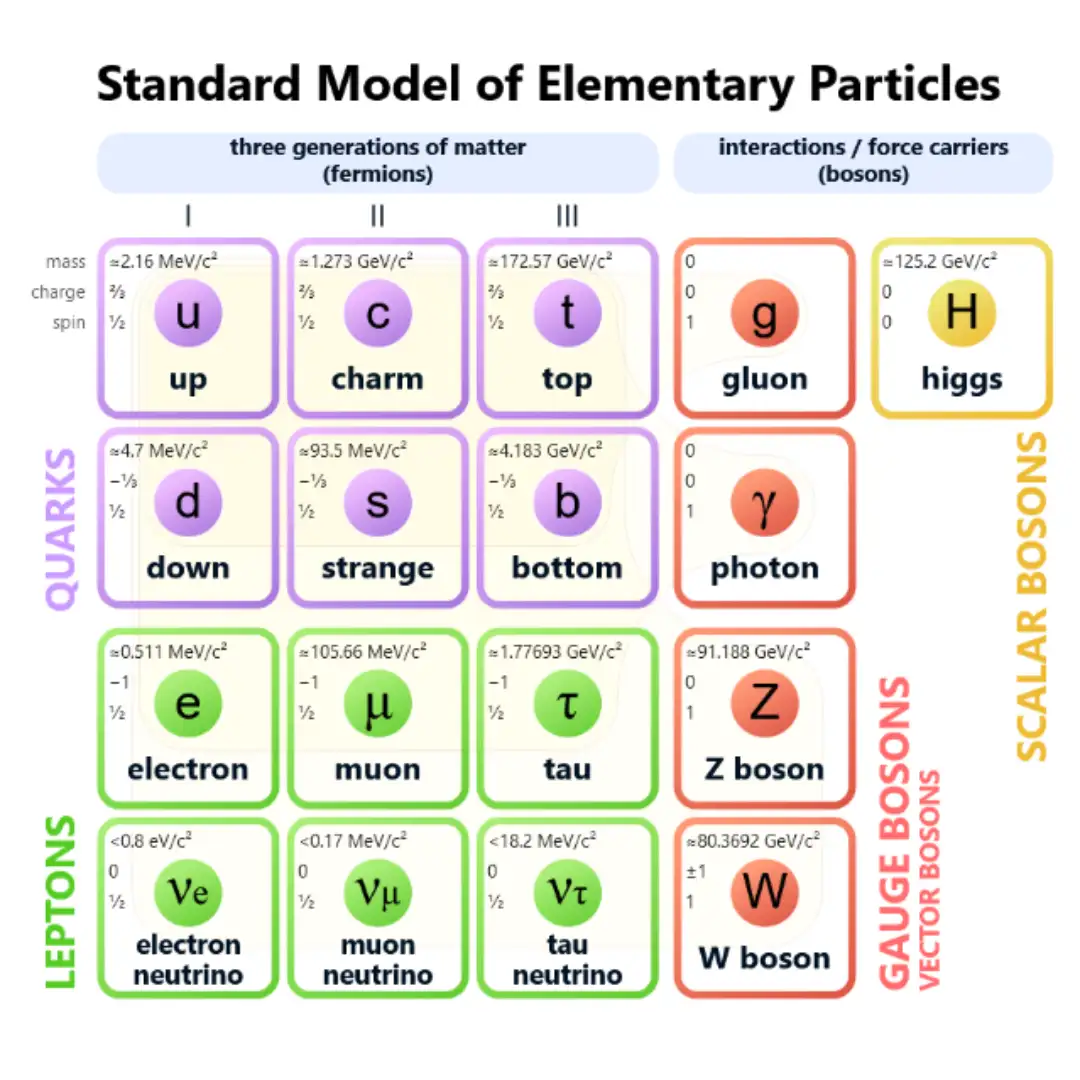

What does science tell us? Science is firmly rooted in this substance metaphysics. In fact, everyday substances like balls and bats never endure forever and are never truly independent. If I break the ball into two and grind it, there is no ball. It no longer exists. The existence of the ball depends on factors like the pressure applied to it (it is crushed under high pressure). Science looks to reduce these everyday substances into combinations of more fundamental substances that are independent, endure and persist forever through all possible change (not just for some time, and under some conditions). Science is basically substance metaphysics in a very sophisticated manner where it abandons the everyday substantial constructs (like chairs, tables, etc) and instead adopts other ones by instead talking about atoms or subatomic particles and now it has reduced all matter to quarks, lepton and gluons etc which serve as the fundamental particles that are independent, endure at all times, and have a bunch of properties that endure together with them - like their mass, charge, spin etc. It seeks to identify the eternally persisting independent fundamental substances and the eternal laws underlying their change of states in a fixed space, like position, velocity, wave-function etc in an imagined fixed mathematical space that is identified with the real world phenomena.

Image Source - Science is sophisticated substance metaphysics!

Image Source - Science is sophisticated substance metaphysics!So, in everyday or scientific metaphysics, the primacy is given to enduring independent substances and change is conceptualized in terms of these enduring independent substances undergoing various transformations. So, substances are fundamental and change is derivative or secondary in Western metaphysics - i.e persisting independent substances are normal, but change needs to be explained.

The Buddha exactly reverses the table and has lifted the curtain upon which we stand on. He considers change as normal and the notions of enduring independent persisting substances as fictions or constructs imposed by our ignorant minds on the flux of various events and processes that we perceive. It is a sign of ignorance and our desire to cling on to something permanent and enduring that causes us to do these things - says the Buddha. This only further traps us into the cycle of rebirth. Liberation comes when we lift this illusion and see the world as it is - a transient flux of impermanent events, each arising, flashing, and then disappearing to cause another such event to arise, flash and disappear and so on. This metaphysics is what we explored in Part 2 as the metaphysics of dependent origination (Saṃskṛta: Pratītyasamutpāda, Pali: Paṭiccasamuppāda). There are no enduring independent substances - just chains of causally connected events, each disappearing after its moment and causing the next to arise subsequently. Reality is not made of independent and enduring persons and substances but by a chain of interlocking physical and mental processes that spring up and pass away. The ball now is not the same substance as the ball at the previous moment - they are both different and that the ball at this moment is not independently existent and instead is dependent on the ball that existed at the previous instant. There is no enduring self that ties all of a person’s life events together and is independently existent of them as well (Saṃskṛta: anātman). Processes are the basic things while “things” and “persons” are derivative - it takes some mental process to construct the idea of “things” and “persons” from the mass chain of perceptions that we are bombarded with. If you had read the articles on Mīmāṃsā and Bhartṛhari (Part 3, 4), this will remind you of indeterminate perception (Saṃskṛta: nirvikalpa). The Buddha says that this indeterminate perception is what is ultimately real and the coating of substances that we impose on this to get the determinate perception is an illusion and arises out of ignorance and desire. This dependent origination is also called the Middle Way by the Buddha because this avoids the one extreme of existence (of enduring independent substances) and the other extreme of nihilistic non-existence (the entire world is an illusion and non-existent). Instead, what it says is that the perceived world exists - just that all that we see exist dependently on other things and their causes at previous instants. This metaphysical concept of dependent origination is mainly found in the Connected Discourses text (Pali: Samyutta Nikāya) and also in the Long Discourses (Pali: Dīgha Nikāya I.12).

For example - a translation by Bhikkhu Bodhi of Kaccānagotta (Saṃyutta-nikāya II 17-18):

This world, for the most part, depends upon a duality — upon the notion of existence and the notion of nonexistence. But for one who sees the origin of the world as it really is with correct wisdom, there is no notion of nonexistence in regard to the world. And for one who sees the cessation of the world as it really is with correct wisdom, there is no notion of existence in regard to the world. “This world is for the most part shackled by engagement, clinging, and adherence. But this one [with the right view] does not become engaged and cling through that engagement and clinging, mental standpoint, adherence, underlying tendency; he does not take a stand about ‘my self.’ He has no perplexity or doubt that what arises is only suffering arising, what ceases is only suffering ceasing. His knowledge about this is independent of others. It is in this way, Kaccāna, that there is the right view. “‘All exists’: - this is one extreme. ‘All does not exist’: - this is the second extreme. Without veering towards either of these extremes, the Tathāgata teaches the Dhamma by the middle: ‘With ignorance as condition, volitional formations [come to be]; with volitional formations as condition, consciousness [comes to be] … [and thus similarly] name-and-form … the six sense-bases … contact … feeling … craving … clinging … existence … birth … aging-and-death [come to be]. Such is the origin of this whole mass of suffering. But with the remainderless fading away and cessation of ignorance comes cessation of volitional formations; with the cessation of volitional formations, cessation of consciousness …‘Such is the cessation of this whole mass of suffering.

Thus, in the words of Gethin (1992: 155),

The point that is being made is that reality is at heart something dynamic and fluid. However one looks at it, reality is a process. True process, true change, cannot be explained either in terms of eternalism (a thing exists unchanging) or annihilationism (a thing exists for a time and then ceases to exist). The process of change as described by dependent origination is thus a middle way between these two extremes, encapsulating the paradox of identity and difference involved in the very notion of change.

What causes us to identify with persistent consciousness and persistent objects? Let us hear from the Connected Discourses (Saṁyutta Nikāya) of the Buddha:

12.1 What is Dependent Origination?

And what, bhikkhus (monks), is dependent origination? With ignorance as condition, volitional formations come to be; with volitional formations as condition, consciousness; with consciousness as condition, name-and-form; with name-and-form as condition, the six sense bases; with the six sense bases as condition, contact; with contact as condition, feeling; with feeling as condition, craving; with craving as condition, clinging; with clinging as condition, existence; with existence as condition, birth; with birth as condition, aging-and-death, sorrow, lamentation, pain, displeasure, and despair come to be. Such is the origin of this whole mass of suffering. This, bhikkhus, is called dependent origination.

But with the remainderless fading away and cessation of ignorance comes cessation of volitional formations; with the cessation of volitional formations, cessation of consciousness; with the cessation of consciousness, cessation of name-and-form; with the cessation of name-and-form, cessation of the six sense bases; with the cessation of the six sense bases, cessation of contact; with the cessation of contact, cessation of feeling; with the cessation of feeling, cessation of craving; with the cessation of craving, cessation of clinging; with the cessation of clinging, cessation of existence; with the cessation of existence, cessation of birth; with the cessation of birth, aging-and-death, sorrow, lamentation, pain, displeasure, and despair cease. Such is the cessation of this whole mass of suffering.

This is what the Blessed One said. Elated, those bhikkhus delighted in the Blessed One’s statement.

12.2 Analyzing Dependent Origination

And what, bhikkhus, is ignorance (Pali: avijjā Saṃskṛta: avidyā)? Not knowing suffering, not knowing the origin of suffering, not knowing the cessation of suffering, not knowing the way leading to the cessation of suffering. This is called ignorance.

And what, bhikkhus, are the volitional formations (Pali: saṅkhāra Saṃskṛta: saṃskāra)? There are these three kinds of volitional formations: the bodily volitional formation, the verbal volitional formation, the mental volitional formation. These are called the volitional formations.

And what, bhikkhus, is consciousness (Pali: viññāna Saṃskṛta: vijñāna)? There are these six classes of consciousness: eye-consciousness, ear-consciousness, nose-consciousness, tongue-consciousness, body-consciousness, mind-consciousness. This is called consciousness.

And what, bhikkhus, is name-and-form (Pali & Saṃskṛta: nāma-rūpa)? Feeling, perception, volition, contact, attention: this is called name. The four great elements and the form derived from the four great elements: this is called form. Thus this name and this form are together called name-and-form.

And what, bhikkhus, are the six sense bases (Pali: saḷ-āyatana Saṃskṛta: ṣaḍ-āyatana)? The eye base, the ear base, the nose base, the tongue base, the body base, the mind base. These are called the six sense bases.

And what, bhikkhus, is contact (Pali: phassa Saṃskṛta: sparṣa)? There are these six classes of contact: eye-contact, ear-contact, nose-contact, tongue-contact, body-contact, mind-contact. This is called contact.

And what, bhikkhus, is feeling (Pali & Saṃskṛta: vedanā)? There are these six classes of feeling: feeling born of eye-contact, feeling born of ear-contact, feeling born of nose-contact, feeling born of tongue-contact, feeling born of body-contact, feeling born of mind-contact. This is called feeling.

And what, bhikkhus, is craving (Pali: taṇhā Saṃskṛta: tṛṣṇā)? There are these six classes of craving: craving for forms, craving for sounds, craving for odors, craving for tastes, craving for tactile objects, craving for mental phenomena. This is called craving.

And what, bhikkhus, is clinging (Pali & Saṃskṛta: upādāna)? There are these four kinds of clinging: clinging to sensual pleasures, clinging to views, clinging to rules and vows, clinging to a doctrine of self. This is called clinging.

And what, bhikkhus, is existence (Pali & Saṃskṛta: bhava)? There are these three kinds of existence: sense-sphere existence, form-sphere existence, formless-sphere existence. This is called existence.

And what, bhikkhus, is birth (Pali & Saṃskṛta: jāti)? The birth of the various beings into the various orders of beings, their being born, descent into the womb, production, the manifestation of the aggregates, the obtaining of the sense bases. This is called birth.

And what, bhikkhus, is aging-and-death (Pali & Saṃskṛta: jarā-maraṇa)? The aging of the various beings in the various orders of beings, their growing old, brokenness of teeth, grayness of hair, wrinkling of skin, decline of vitality, degeneration of the faculties: this is called aging. The passing away of the various beings from the various orders of beings, their perishing, breakup, disappearance, mortality, death, completion of time, the breakup of the aggregates, the laying down of the carcass: this is called death. Thus this aging and this death are together called aging-and-death.

The Buddha thus gives an algorithm for what causes all this. Ignorance of the true states of affairs is the first step in this 12-process cycle that leads us to fall into desire (volitional formations) which makes us deluded by having us see ourselves as a persistent human being by imagining a consciousness which further leads us to categorize perceptions into persistent forms with names when a sense organ comes into contact with a sense object. This leads to feeling which leads to craving and clinging and is the root of all existence (as persistently existing) which fuels the cycle of birth, old age and death. An enlightened man severs himself from this cycle by seeing everything as they are - that nothing persistently exists independently, everything originates depending on its precedent causes and perishes causing its antecedent effects. I think this is the most important concept of the Buddhist message. Later philosophers in both the Theravāda and the Mahāyāna traditions will systematize it philosophically.

Read next part in the series - The Intellectual Traditions of the East For Beginners, Part 6 | Nāgārjuna and Śūnyatā