# Bodhas

The Intellectual Traditions of the East For Beginners, Part 3 | Classical Schools of Indian Thought - Mīmāṃsā

21 October, 2024

6966 words

share this article

In the previous two parts of this series (Part 1 and Part 2), we saw the philosophical traditions of the Upaniṣads and the beginnings of Buddhism. The period from the composition of the Upaniṣads to the times of Buddha form the ancient roots of Indian philosophical history. In this article, we enter the next major historical period in Indian philosophy - the age of the sūtras. Also, by this time, Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and other movements had split into a number of rival schools that were arguing with each other vigorously to establish their philosophical supremacy. These schools were based on discipleship and oral learning and arguments. Unlike in the West, philosophy in India was not identified with written texts. The real philosophy happen orally via a guru-śiṣya (master-disciple) tradition. But, we do have written texts associated with each school but they play a different role. The first type of text associated with each school is called a sūtra. A sūtra (Sanskrit: thread) is a set of highly condensed codified statements. They were supposed to be mnemonic aids given by the teacher, meant for the students to remember the key arguments - like a cheat sheet made from reading a book. The sūtras were written down much earlier. But later, as the schools evolved, there came to be written commentaries to expound the contents of the sūtra. This commentary is called a bhāṣya. There could be more than one commentary for a given sūtra and schools could split into sub-schools depending on which bhāṣya they accepted as canonical.

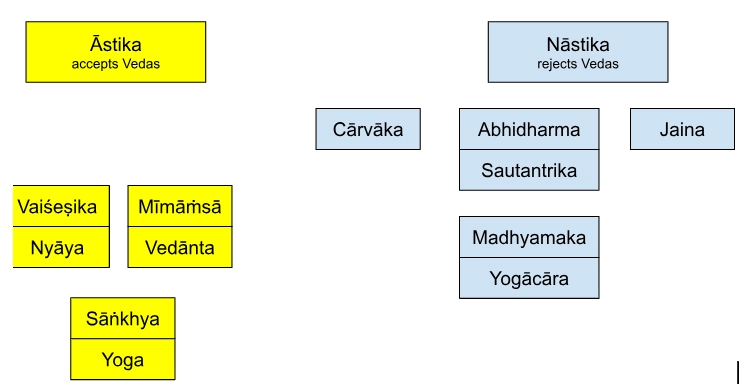

Traditionally, the various schools have been classified as follows:

But, note that all these schools were contemporaneous and vigorously debating with each other so that we have to understand one of them to understand the other. So, first, we will explore each of these schools individually along with their important ideas and then return later to provide a detailed and systematic analysis of all the schools together in various topics. Note that these are just approximate and a non-exhaustive schematic. Not every thinker thought of himself to be in exactly one of these schools. There were individuals and other schools who did not fit here and there are sub-schools too within quite a bit of them. So, it is useful to start with as a rough guide. In this article, we will deal with the Mīmāṃsā school.

The Defence of Ritual and Philosophical Realism

The Mīmāṃsā school has a sūtra associated with it and is called as Mīmāṃsā sūtra and is attributed to the sage Jaimini. The famous bhāṣya (commentary) for this was authored by Śabara. Then, the school split into two rival factions based on later interpreters - Kumārila Bhaṭṭa and Prabhākara Miśra.

The Mīmāṃsā school’s main aim was to defend the rationale and performance of the Vedic rituals that formed an important part of Hindu religious life. While Buddhism and Jainism were openly challenging the efficacy and rationale of the rituals, other schools of Hinduism also seem to have neglected them or relegating them to the sidelines (even though accepting them as authoritative), focusing on the later Upaniṣadic philosophical part of those texts where the rituals are internalized and allegorized. While the Mīmāṃsā school did not deny that mokṣa was the ultimate aim of life, it took as its main task to defend the older ritualistic aspects of the Veda. Similarly, another school called Vedānta took it upon itself to build a systematic philosophy from the Upaniṣadic part while not focusing on the ritualistic part. So, eventually, the two schools Mīmāṃsā and Vedānta eventually came to be seen as a single whole with the former defending the ritualistic part (karma kāṇḍa) while the latter defending the philosophical part (jñāna kāṇḍa). That is why they are often paired together and discussed successively.

Consider for example, a harsh critique of Vedic rituals by a Buddhist named Dharmakīrti in his own commentary on his own text named Pramāṇavārttika (Bk1, Verse 340):

Accepting the authority of the Vedas, believing in individual agency, hoping for merit from bathing, taking pride in caste, undertaking rites for the removal of evils: these are the five signs of stupidity, the destruction of intelligence.

These are the kinds of harsh critiques that the Mīmāṃsā tradition had to respond to. I start with the Mīmāṃsā school because its philosophy is rooted in realism. What should be the worldview adopted by anyone who thinks that the performance of a sacrificial ritual (as instructed in a sacred text) for a certain god gives a certain outcome?

The ritualistic part of the vedic texts came under three major kinds of criticism and are recorded in the sūtras of the Nyāya tradition:

- Falsity: The promises of the ritual are not always fulfilled. For example, a house holder might perform a ritual that is supposed to make him rich, but turns out - he is not rich!

- Inconsistency: The Vedic texts sometimes offer different opinions in the same situation.

- Repetition: The Vedic texts often repeat the same things again and again.

There is standard refutation of these texts in the same tradition. For instance, if a ritual does not yield the promised result, it must be the faulty execution of the ritual. The inconsistencies are resolved by taking into account their context and place. And of course, important things are good to be repeated.

The main contribution of the Mīmāṃsā is that of exegesis. Most of the Mīmāṃsā sūtras are about this. The Vedic texts at many places do not give details as to the performance of the ritual. So, the Mīmāṃsā tradition extrapolated and interpreted these to come up with a complete consistent algorithm to perform all the rituals. They fill out the gaps in the Vedic text. When a ritual is insufficiently described, the tradition uses methods to remedy this. To complete the instructions of an insufficiently described ritual, this method looks for another similar and related but sufficiently described ritual and uses that as a model (prakṛti) to borrow from and transfer (atideśa) onto the given ritual by appropriate thinking (ūha) and after removing (bādha) the things that are specific to the model ritual.

Subordination of Desire and Gods to the Ritual

The school has the following basic assumptions:

- Humans desire happiness.

- They take action to implement that ritual.

- As a result of this action, they indeed get pleasure (prītiḥ).

This is indeed the position that has to be taken by the Mīmāṃsā school if they have to defend the Veda because most of the Vedic ritual sentences are injunctional - they are of the form: “If you want so and so, do the ritual so and so”. In the Vedas, one rarely encounters statements to perform the ritual for just its own sake. Without the desire that is impelling (codana) a person, the conditions for performing the ritual would not apply (remember that the format is - IF YOU WANT…PERFORM) because of the injunctive format of the sentence. Of course, one sometimes finds a critic that some rituals in the Veda specify no intended outcome or motivating desire but Jaimini goes one step further and says that heaven (svarga) is the default object of desire, is the highest good (niḥśreyasa) . The default outcome for heaven is happiness and happiness is desired by all (Mīmāṃsā Sūtra and Bhāṣya: Chapter 4, Pada 3, 15-16).

At this point, it may be useful to compare the concepts of sacrifice in the religions of the Semitic traditions and the Vedic tradition. In Semitic religions (eg. Judaism, Christianity, Islam), desire is not the primary motivator for the sacrificer to perform the sacrifice. The sacrificer is under a form of sin and the performance of the sacrifice removes the sin in question and hence restores the person into a right relationship with God. For example, the death of Jesus Christ on the cross is supposed to be a sacrifice for the original sin that is on all human beings through Adam’s disobedience to God in the Garden of Eden. This is not the case with Vedic sacrifices that are based on the desire of the sacrificer to obtain something of value (artha).

Now, imagine what a controversial position it must be, to take such a position, to give primacy to material desires, in an environment with Buddhism, Jainism and other Hindu philosophical schools emphasizing on going away from material desire which would lead to liberation. So, it might appear that Jaimini is proposing a materialistic philosophy of selfish desires motivating the performance of rituals for the sake of defending them. But here is the twist to the entire story. Jaimini, instead subordinates desire to the ritual. For Jaimini, what matters the most is the ritual. But the vedic texts say that only a person with a particular desire should perform that particular detail. What Jaimini implies is that the ritual is intrinsically valuable for its own sake (svārtha). The desire is simply a precondition, a stage or an environment, used by the ritual to make it happen. That is, the ritual uses the desire of the sacrificer as a tool to realize itself! Even the gods are not anything special in this framework. The Mīmāṃsā does not tell that one should sacrifice to a god to please him/her. The gods simply are placeholders for the indirect object/recipients of the sacrificial ritual! The gods exist only in name - that is to say, only insofar as their names are mentioned in the performance of the rituals - they are mere placeholders. Mīmāṃsā argues that the Gods named in the Vedas have no existence apart from the mantras that speak their names. To that regard, the power of the mantras is what is seen as the power of the gods. Sacrifices maintain the cosmic order and a sacrificial ritual is described by the tradition as the “womb of cosmic order” (Sanskrit: Ṛtasya Yoni). It renews this cosmic order by using the desire and the sacrificer as its agent! Some examples to dramatically illustrate this are given below:

- In a ritual called asthi-yajña, it is prescribed that if the sacrificer dies mid-way in the ritual, then his bones be placed in an antelope skin and this may be made to perform all those acts which are for the sake of the sacrificial act!

- In a certain yajña for rain is decided to be performed at a given time, it should be continued even if rain is gotten before that!

Thus, we see that Mīmāṃsā on the one hand goes diametrically opposite to the philosophical direction of its age by defending traditional rituals and the desires that motivate them to be performed, yet it also captures that spirit of its age by humbling that desire and the gods to the performance of the ritual itself that renews cosmic order.

Sources of Knowledge in Mīmāṃsā

Let us first get familiarized with the Indian terms in epistemology. I only roughly translate them but note that the English translation does not technically match the sense in which it is understood in Western philosophy. Of course, if you are not familiar with Western philosophy, then it is good - you won’t get confused! Otherwise, suspend any Western technical connotation of these terms - they are not exactly correspondent. In another article where a systematic comparison is being done between the various Indian schools, the difference with Western philosophy is also discussed. The following are some basic terms in Indian systems of epistemology:

- Pramā = Knowledge episode (the moment when you get any realization)

- Pramāṇa = Means and sources of pramā (how did you arrive at your pramā)

- Prameya = knowable / object of pramā (what do you get to realize about)

- Prāmāṇya/pramātva = truth of pramā (what makes a pramā true?)

- Khyāti = Error

The Mīmāṃsā tradition recognises the following six sources and means of knowledge (pramāṇa):

- Pratyakṣa (Sense Perception)

- Anumāna (Inference)

- Upamāna (Analogy)

- Arthāpatti (Implication)

- Anupalabdhi (Non-perception) - only recognised by the Bhaṭṭa sub-school

- Śabda (Testimony of a reliable person / text / vedic scripture)

(Note: Memory is not included in this list because it is considered to be not a source of new knowledge and only a carrier of old knowledge).

Perception:

According to Mīmāṃsā, perception happens when sensation comes into contact with a sense object. According to Mīmāṃsā, there are two kinds of perception in two stages, the first stage is called nirvikalpa (indeterminate) and the second savikalpa (determinate). Indeterminate perception is that raw perception at the first moment of association between senses and the sense object, had by infants, where there are no categories or differentials imposed on the perceptual stream. On the other hand, determinate perception is when we objectify this perception and categorize them into object classes and particular objects with certain qualities. Both the sub-schools of Mīmāṃsā agree that this objectification is not something that the mind imposes on the indeterminate perceptions (like Kant says in Western philosophy) but that they are always there, intrinsic to the indeterminate perceptions themselves (somewhat like Aristotlean). That is, the fact that this is a ball is not something that the mind imposes on perceptions but it is a part of the reality of the indeterminate perception itself. Only memories of previous experiences, enables one to apprehend them. That is, if I look at a room, the reason I am able to convert the sight that falls onto my eyes (indeterminate sight) into persistent objects (vastu) of various classes (jāti) (eg. balls, tables, chairs, floor, ..) with certain qualities (eg. color, brightness, numbers, …) is simply because I have seen various other times, all these objects with qualities and can remember them and hence recognise these objects and qualities in comparison with my memory of other observations. That is, objects and their qualities that persist over a duration of time, though intrinsic to the indeterminate perceptions, are perceived by bringing the present perception in relation to the memory of the past ones and realizing its character as involving universal and particular. Kumārila and Prabhākara both agree in holding the indeterminate and the determinate perceptions to be equally valid. Whereas, according to the Buddha, if you remember (from the previous article), only the indeterminate perceptions (part of the skandhas) are valid and any categories we put on them like those of persisting objects that persist for a finite duration of time, with persisting qualities that connect and relate these streams of the indeterminate perceptions together, is simply ignorance. The Upaniṣads (if you remember from another previous article), on the other hand, goes to the other extreme and ask us to search for things that are absolutely undifferentiated and eternally persisting like ātman, brahman, sat.

The Mīmāṃsā school thus believes in realism- it believes in individual beings with persistent selfs and believes in an external objective material world intrinsically made of substantive persisting objects so that rituals can be performed for desires by persisting subjects that have intended consequences for them.

Inference:

Śabara says that when a certain fixed or permanent relation has been known to exist between two things, under certain conditions, then we can have the idea of one thing when the other one is perceived in that condition, if that relation does not depend on any other eliminable condition. This kind of knowledge is called inference. In this class, there are several types of inferences - coexistence and causation. They are:

- Co-existence (pratijñā) (eg. contiguity of the constellation of Kṛttikā with Rohiṇī)

- Causation (hetu) (eg. inferring rain from seeing clouds)

- Identity (dṛṣṭānta) (seeing a male person and inferring he is a man - particular => universal)

Note: The second type - causation - also involves situations when two events are not related by cause and effect but are both concurrently correlated caused by a third factor. Then, inferring one event based on the other event in the presence of the third factor is also under this category of causal inference. An example would be seeing rise in sweater sales in an area and inferring fall in cool drink sales in the same area - both causally affected inversely by temperature.

In all such cases the thing (e.g. fire) which has a sphere extending beyond that in which the other (e.g. smoke) can exist is called gamya/vyāpaka and the other is called vyāpya/gamaka and it is only by the presence of gamaka in a thing (e.g. hill, the pakṣa) that the other counterpart the gamya (fire) may be inferred.

An interesting view in Indian philosophy is that the general law which is the universal coexistence of the gamaka with the gamya (e.g. wherever there is smoke, there is fire) is not taken as a valid ground for inference in Indian philosophy in general - cannot be the cause of inference, for it is itself a case of inference.

In Western philosophy, this inference would be split into two stages - induction and deduction.

Stage 1: Seeing smoke with fire lots of times => Law: Smoke and fire coexist (INDUCTION)

Stage 2: Using the Law: Smoke and fire coexist => I now see smoke. Hence, there must be fire (DEDUCTION)

In Western philosophy, induction involves formulating general laws and relations (where there is smoke, there is fire) from observations of lots of data (1000 observations of fire and smoke together). And then, deduction involves applying these laws and relations to incomplete data (I see only smoke) and predicting the unobserved dependent (there should be fire).

The West sees the deduction step as infallible because it involves going from the general to the particular. It sees the induction as uncertain and is stuck with the problem that induction cannot be proved to be reliable (all methods to prove induction to be reliable involve using the principle of induction itself in some form or the other, thereby making it circular). Just google “The problem of induction in Western Philosophy” and you will see lots of such discussions. Whereas Indian philosophers did not split the inference into an inductive and deductive part, simply because maybe they realized that the generic laws that ground deduction have to be got by induction only and since induction is already doubtable in principle, they would have clubbed both into one inference and realizing that it is impossible to prove induction, declare it as another independent source of knowledge. Thus summarizing, the experience of a large number of particular cases in which any two things were found to coexist together in another thing in some relation, when associated with the non-perception of any case of failure, creates an expectancy in us of inferring the presence of the gamya in that thing in which the gamaka is perceived to exist.

Analogy:

This is a distinct category. The standard example for this is when a man who has seen a cow (go) goes to the forest and sees a wild ox (gavaya), and apprehends the similarity of the gavaya with the go, and then cognizes the similarity of the go (which is not within the limits of his perception then) with the gavaya. This is called upamāna (analogy). It is regarded as a separate source of knowledge, because by it we can apprehend the similarity existing in a thing which is not perceived at the moment. It is not mere remembrance, for at the time the cow was seen, the wild ox was not seen, and hence the similarity also was not seen, and what was not seen could not be remembered. The difference of Prabhākara and Kumārila on this point is that while the latter regards similarity as only a quality consisting in the fact of more than one object having the same set of qualities, the former regards it as a distinct category.

Implication:

The standard example given in the text for this is when one observes that when a person is not in his house and thereby concluding that the person should be outside his house. Let us hear in the words of Kumārila himself in Ślokavārttika 8.1:

When a fact ascertained by any of the other pramāṇas is found to be (logically) inexplicable except on the basis of a fact not so ascertained - the assumption of this latter fact - is what constitutes arthāpatti (implication).

This implication is usually confused with abduction in Western philosophy which is basically the best explanation. But here, an arthāpatti is not the best possible explanation but the only possible explanation without which there is a logical impossibility to something that is already known. Here, without resorting to implying that the person is outside the house, would lead to a logical contradiction in the presence of the fact that he is not inside the house. One might ask, is it not reducible to a combination of perception and inference? There is a subtle thing here. Mīmāṃsā argues that infering something on the basis of induction and deduction is different from analogy. If I infer the presence of fire from the perception of smoke through correlation of smoke and fire, it is still possible for me to be wrong. I would be surprised to learn that there is no fire and just smoke but it is not logically impossible. But on the other hand, there is no logical possibility for a man who is not inside his house to also not be outside his house because logic for sure requires that a person should either be inside his house or outside his house.

Non-perception:

This is again very simple. Since perception is defined as the contact of the sense organ with a sense object in the Mīmāṃsā tradition, the fact that I see inside my room and do not see an elephant it cannot be a source of perception since there is no such sense object as a “non-elephant” that is making contact with my sense organ (eye). So, non-perception (anupalabdhi) should be a separate source of knowledge. Again, one might argue that this can also be reduced to perception since I observe all objects in my room and they are not elephants.

Mīmāṃsā is the school with the highest number of sources of knowledge (pramāṇa). Other schools will cut off some of these. For example, no other school except the Advaita Vedānta school considers non-perception as a distinct source of knowledge. Implication is not considered as a separate source of knowledge but reducible to inference in many other schools. The radical materialist school of Cārvākas consider only perception as a valid source of knowledge. Most Bauddha schools and the Vaiśeṣika school only consider perception and inference. Jainas include only perception, inference and testimony. The Nyāya school includes four: perception, inference, analogy, and testimony. We will see them all, in detail, in due course. But do remember this epistemological classification of sources of knowledge, it will be useful for future articles when we discuss other schools.

Testimony:

All Hindu schools except the Cārvākas accept testimony as a valid source of knowledge. Testimony, in Sanskrit śabda, literally means a sounded word. It is basically communication from a trustworthy person. In fact, we use testimony of competent people for much of our knowledge. But why is it distinct from perception or inference? If someone says that Antarctica is cold, in principle, I can actually go to Antarctica and perceive the chills. If a doctor says that this medicine will cure my fever, in principle I can actually study medical science myself and establish it through scientific inference. So, much of our testimony is actually reducible to perception and inference and we treat it as a shortcut because we do not have the time or energy or means to do the perception or inference ourselves even though it is possible in principle. We use testimony as a shortcut to avoid doing the hard work of following the other pramāṇas ourselves. So, can we omit testimony as a separate source of knowledge? There are two reasons as to why one may not choose to do so.

First, what if there are testimonies that are not reducible to the other pramāṇas? Those should be the real deal. If there are no such cases, then testimony can be omitted as a pramāṇa and be subsumed under other pramāṇas. The testimony of vedic scriptures will come under this category and will be discussed in a separate section.

Next, even if in principle, a testimony of a trustworthy person can in principle be verified by himself (but not actually done), some schools argue that it is not a matter of perception and inference. Inferring the meaning of what a person says is not perception as it relates to language and meaning. Also, the understanding of meaning of an utterance from the sound is not inference as there is neither a gamya nor a gamaka that are correlated. So, it has to be covered under a separate philosophy of language.

Correctness and Error in Mīmāṃsā: Innocent Until Proven Guilty

Given that these are the sources of knowledge, how do we decide if a cognition from any or many of these sources constitutes a valid knowledge episode (pramā) or not? For example, if I see a rope in dim light and then think of it as a snake, I have used perception but that is not a knowledge episode as it is not correct knowledge. All Indian schools agree that truth is the only criterion that distinguishes knowledge episodes (pramā) from false cognitive episodes. But they disagreed on what makes a cognitive episode true, or how to establish the truth of a cognitive episode true, thereby making it into a valid knowledge episode?

The Mīmāṃsā argues that a knowledge episode that is gotten, is by default, always true intrinsically, by itself (svataḥ prāmānya). Why? The argument is that if we need another knowledge episode to establish the truth of a given cognitive episode that gave rise to that knowledge episode, one can ask the same thing about what makes that other cognitive episode true and hence this will go on for an infinite regress. In other words, if I need to justify why something is true, I have to justify the justification and then justify the justification of the justification and so on ad infinitum. But, to avoid that, how can I assume that every cognitive episode is true by default? Avoiding that infinite regress is indeed necessary but one cannot simply throw away the need for justification. It is also true that sometimes these tools like perception and inference can be erroneous - I might mistake a rope for a snake in dim light and I might infer something incorrectly due to a mistake in some calculation. But if I keep on cross checking the correctness of every knowledge episode by another knowledge episode, then it only leads to infinite regress and we cannot know anything and this would lead to skepticism. What then is the solution?

The solution adopted by Mīmāṃsā is that every knowledge episode is “true if not falsified”. It is analogous to the idea that one is innocent until proven guilty, in a legal system. That is, as long as the knowledge episode is not found to be contradictory or falsified by a later cognitive episode (bādhakajñāna), we can keep believing it to be valid. Validity of a knowledge episode simply means not being falsified. False cognitive episodes, according to this school, arise only due to imperfections or errors of the human apparatus (karaṇadoṣa) - the observer. For example, the vision can be imperfect due to dim light, the calculation might turn out incorrect because of an unintentional mistake in a multiplication step, a loss of memory, a false testimony and so on. But truth is always objective and intrinsic to a knowledge episode - its truth is objective and is not dependent on anything else. So, the argument is that there is no criterion for something to be true; there are only criteria for something to be false. Thus the validity of knowledge, certified at the moment of its production, need not be doubted unnecessarily when even after enquiry we do not find any defect in sense or any contradiction in later experience. All knowledge except memory is thus regarded as valid independently by itself (until it is invalidated later on). Memory (smṛti) is excluded because the phenomenon of memory depends upon a previous experience, and its existing latent impressions, and cannot thus be regarded as arising independently by itself. What are the various sources of error? Mīmāṃsā recognises only some types of error (other schools recognize more).

Sources of Error in Mīmāṃsā (Khyātivāda):

- Unreal Object (Satkhyāti) - The standard example is mistaking a rope for a snake in dim lighting. This class of error consists of assigning the wrong object class to a perceived object due to insufficient grounds of perception.

- Non-cognition (Ākhyāti) - by Prabhākara Mīmāṃsā - This happens for example, when one is ignorant of the properties that distinguish two object classes and hence one misidentifies the object class by noting only the properties that are only similar to both the classes. Consider a scientifically ignorant person mistaking a gold plated ornament for a gold ornament. Here, the mistake is because one is ignorant of the properties that distinguish between gold ornaments and gold plated ornaments (like the value of density) and hence mistakes a gold plated ornament for a gold ornament.

- Cognition as Another (Anyathākhyāti) - by Bhaṭṭa Mīmāṃsā - Here, the mistake happens because one is reminded of another object while seeing an object and the memory interferes and prevents us from seeing the distinct properties that distinguish the object in memory and the actual object. It is not due to ignorance but a distraction.

The Status of the Veda in the Mīmāṃsā

In Islam, it is believed that God sends different revelations to different peoples. The Torah for the Jews, the Gospel for the Christians, and finally and most definitively, the Qur’an for the Muslims. The Qur’an is believed by Muslims to be an eternal book authored by God and sent to mankind through the Prophet Muḥammad. The Mughal prince Dara Shikoh, one of those rare Mughals, who was interested in the Hindu philosophies, believed that the Upaniṣads was the revelation of God to the Hindus. But the Mīmāṃsā tradition would strongly disagree with him. Because they held that the Veda, while being eternal (nitya) was without any author (apauruṣeya). The Veda was not written by anyone. Nor was it “sent”. The vedas had no author. The seers who expounded it were not like prophets in the Abrahamic traditions who got the revelation from God and transmitted them. The seers simply grasped the eternal text that has always existed. The seers were not conduits from the divine to the human realm but simply between the past and the present. This is because no such conduit is needed as it has always been there as an eternal source of knowledge. Thus, the Mīmāṃsā, while being like a St Augustine in defending the veracity of scripture and committing to it with absolute fidelity, is also as atheistic it can get, since the gods play absolutely no role in authoring the scripture and gods hardly come up in its philosophy.

What are the advantages of having such a position? An authorless text that is a source of knowledge cannot contain any error. This is because it is free from any defects of the mind of the person who composed it as there is no composer in the first place. Remember that any cognitive episode based on the sources of knowledge is by default true, unless it is falsified. And falsification comes from human or subjective imperfections. So, if the Veda is authorless, then it can never be falsified on the grounds of unreliability of the subject! But, can the vedas be falsified based on our own perceptions and inferences? The Mīmāṃsā recognises that while all other sources of knowledge (like perception, inference etc) tell us “what is” and the facts out there, only the Veda can tell what “should be”. No amount of perception, inference or analogy that determines “what IS” can falsify any knowledge of the form “what SHOULD BE”. While all other sources of knowledge are only descriptive of things, only Vedic language has the capacity to inform us about dharma as something that needs to be brought about. Without the śabda (textual) as a source of knowledge, one can never determine what should be done (dharma).

When a sacrifice is performed according to the injunctions of the Vedas, the Mīmāṃsā tradition demonstrates using the scriptures themselves that, a capacity which did not exist before is generated either in the action or in the agent. This capacity or positive force called apūrva produces in time the beneficial results of the sacrifice (e.g. leads the performer to Heaven). This apūrva is like a potency or faculty in the agent which abides in him until the desired results follow.

Language in the Mīmāṃsā

The Mīmāṃsā believes that the Vedas are eternal text. But Vedas are basically texts composed in a human language (Sanskrit). So, that logically implies that language is permanent and eternal! Hence, in this section we will see how the Mīmāṃsā view on language is shaped by its belief in the Veda. Before that, again let us give a prelude to the Indian view of philosophy of language, in general. Indian philosophers developed their own terms again that do not match exactly with any European counterparts. One such case are the pairs of concepts in opposition - shabda and artha. The former is commonly translated as “word” and the latter as “meaning” but exactly identifying what they are was actually the main focus of the various schools. So, they may better be understood as “signifier” and “signified” respectively. In Indian view, shabda is a linguistic element whereas artha is an external referent or an idea or an object. The following are basic vocabulary.

- Varṇa = phoneme (alphabet)

- Pada = word

- Vākya = sentence

The Mīmāṃsā propounds that varṇas are the basic units of language structurally but the minimal unit of language that conveys meaning is a word. Thus, in this school, śabda is identified as a word and may be translated so. They think that each word is linked intrinsically to meaning which is basically a universal (concept). For example, the Sanskrit word “go” refers to the universal “cow” - a given class of animals. There is an intrinsic connection between the word “go” and its meaning “cow” according to Mīmāṃsā . Why? The word go occurs in the Veda. If the veda is eternal, and the dharma established it is eternal, then the word, meaning and the connection between them - all of them should be eternal and fixed as well. So, the phonemes (varṇas) exist as potencies eternally and so do the words and their connection to their meanings.

Mīmāṃsā offers other batteries of arguments to show that this system of language is indeed eternal and uncreated. First, it argues that languages are always learnt as children watching and hearing adults using it. Things have never been otherwise. So, one may assume that language always has been passed down from generation to generation and is eternal (it also believes that the universe is eternal with no beginning and end). One might ask - after all, a spoken word is a temporary puff of air and vanishes soon but the word itself is eternal - it is a bunch of sounds. But the tradition says that the word itself exists independent of human vocal systems and eternally, tied to its universal (that carries its meaning), like a reservoir, for people speaking the language, to pick and use from it, whenever they want. The Mīmāṃsā view is that a Sanskrit word (pada) is a permanently fixed sequence of timeless, unproduced and imperishable phonemes (varṇa), which are manifested as audible sounds. It is the sequence of these eternal sounds that create words and act as conveyors of meanings or signifiers (vācaka) and express their significations (vācya). The signifier–signified relation is an eternal (nitya) and has innate power (śakti/sāmarthya) in words to express their meaning. A given word stands for a limitless number of objects: We say that a single word like ‘go’ is uttered eight times and not that there are eight words of ‘cow’. The word–object connection (śabda-artha-saṃbandha) cannot be a human creation. It cannot be established every time we use a particular word. But we have no traditional recollection of anyone originally fixing the references of words. Even if one can learn the meanings of some new words afresh, there is no way to introduce an entire language as such. It is impossible to learn to speak and understand one’s first language without learning to engage in linguistic activity by observing, acting and speaking. Once we are competent language users, we can learn new words by having them explained by using existing words but it is inconceivable that the entire language began from a situation where there was no language at all and people created words and assigned meanings to them.

How does language work and correspond to reality? Mīmāṃsā split into two mainly because of that. Kumārila along with the earlier Śabara propose the following, and their view is called abhihitānvayavāda:

- A single word by itself has a meaning. For example, the word “cow” stands for a class (jāti / ākṛti) of objects. But that meaning is particularized by its presence in a sentence in a particular context. Eg. In the sentence “Bring the cow”, while uttered by a priest in a ritual, the word “cow” refers to a particular cow that is tied nearby which is to be used for the ritual.

- The meaning of a sentence is a function of the meanings of its constituent words after contextual particularization. This means that the meaning of a sentence is simply the combination of individual meanings of words. The meaning of a mere word “cow” brings to mind a class of animals (cowness) whereas the meaning of the word “cow” in the sentence “Bring a/the cow” refers to a particular concrete cow.

The central argument is that the cosmos is made of eternal words (like “cow”) on the one hand, and also eternal universals (the idea of a cow / cow-ness) on the other hand. There is an eternal relation between these two eternal realms (śabda-artha-saṃbandha). The particular utterance of the word “cow” from the mouth of a particular person at a particular time is the manifestation of the eternal word “cow” and the particular cow that it refers to, in the context of his uttered sentence is a manifestation of the eternal universal of the concept of “cow”. So, there is a movement from the universal conceptual level to the specific concrete level when one goes from the idea of cow to an actual particular cow and also when one goes from the eternal word “cow” to a particular utterance of the word “cow” at a particular time by a particular person. There is an eternal word “cow” that relates to the eternal universal (idea) of “cow”. Then, there is a particular utterance of the word “cow” from a mouth of a person, at a particular time, that relates to a particular “cow” in context - both of them are temporary mundane manifestations of the idea, word and their relation in the eternal realm.

By contrast, Prabhākara says that while words indeed are legitimate constituents of a language, and that the connection between language and reality is fixed and natural, it proposes that words do not have any meaning by themselves, and must appear in a sentence to have any meaning at all. Word meanings according to him are primarily understood when they are uttered and bring about things, rather than corresponding to a class of already existing objects. This view is called anvitābhidhānavāda. Prabhākara argues that no child learns a word separately. All he hears are sentences and he discerns and learns meanings of words only by substitution. For example, a child learns the meanings of the words “cow” and “horse” by observing what is the difference between the actions that result from the utterance of sentences like “Bring the cow” and “Bring the horse”. So, we should always look at a word in context in a sentence and never examine it in isolation. This may sound implausible but consider the sentences “At once, I will come” and “The cow looked at me”. The word “at” seems to not have any common meaning in both these sentences.

Read next part - Bhartṛhari, From Language to Liberation