# Bodhas

The Intellectual Traditions of the East For Beginners, Part 2 | Pratītyasamutpāda (Dependent Origination) - Buddhist Metaphysics

29 August, 2024

5478 words

share this article

In the previous part of this article, we saw the beginnings of systematic philosophical thought in India that began in the Upaniṣads and its idea of a single ultimate reality that underlies, persists and grounds the phenomenal world of multiplicities which is referred to by various names in various realms - sat [in the material realm], ātman [in the realm of ourselves] & brahman [in the divine realm]. The Upaniṣads proclaim that behind this phenomenal world of everything there is, is a simple, single, undifferentiated Being that somehow is the “source” of all. An intimate epistemic realization of that Reality would liberate us from the endless cycle of saṃsāra.

In this article, we explore another school that arose in India, soon after, that thought otherwise and rejected the presence of any constant that persists in the ephemeral world of phenomenal change. This is none other than Buddhism. Although Buddhism would ultimately die out in India by the 12th century, it had a bright future outside of India and served as the evangelical wing of Indian civilization. It would immensely influence and get influenced by other schools and various schools of Buddhism would compete with those of Hinduism, Jainism and other schools for support from peoples and states.

Suffering yet Smiling

Readers here must be familiar with the usual life story of Buddha. He was born a prince, Siddhartha, in the kingdom of Kapilavastu in modern day Nepal, in about the sixth century BCE. His parents brought him up in luxury without exposing him to the outside world. One day when he took a stroll outside the palace, he saw people suffering from various conditions and this hit him so hard that he renounced his family to contemplate on the cause of suffering and how to end it. He tried the extreme ways of the ascetics, Upaniṣadic sages, which gave him no answers. One day while he was meditating under a bodhi tree, he found the solution to the problem of suffering and taught his disciples about it. He eventually attained nirvāṇa at the end of his life. You will definitely know this much if you have a decent exposure to Indian history and you might also have read some Jātaka tales - the stories of the Buddha’s various past lives. But what did he exactly teach? What was his metaphysics? That is what this article is for.

The first and main realization of Buddha is that life is full of suffering. This is what informs the entirety of the Buddha’s metaphysics. That might seem a bit strange to you. Surely, we do suffer a lot but are there not moments where we truly enjoy and relish too? Maybe during Buddha’s days it did make sense - it was a world without modern medicine and technology but surely now aren’t we doing great? Part of this overly negative connotation might be due to a misunderstanding of the word that is translated as suffering here - in Saṃskṛta, the word is duḥkha and in Pali, dukkha. In everyday usage especially in modern languages, the word means suffering but in this context, the word actually stands for something lighter - it can be translated more accurately as “uneasiness” or “unpleasantness” or “dissatisfaction”. That is what is the literal etymological meaning of the particle “duḥ” in Sanskrit. Eg. In Sanskrit, “su+labha = easy to get” while “duḥ+labha = durlabha = not easy to get”. Still, is all of life like that? The Buddha says yes. He is saying that if you think otherwise, you are like a drug addict who thinks that you are having a good time while actually happening to be ruining your life without knowing it under the influence of the illusion caused by the drug. Buddha says that any pleasant experience, no matter what, is always transitory; and hence after it becomes over, we end up craving for more. Therefore this desire for more pleasant experiences and avoiding unpleasant experiences makes us trapped in a vicious positive feedback cycle. This continuous craving for pleasure is called by the Sanskrit term tṛṣṇā (Pali: taṇhā) which literally means “thirst”. There are only three possibilities when you crave for any pleasure.

- If you get the pleasure that you have craved for, after sometime you only end up craving for more of it (tṛṣṇā) and end up in duḥkha because you cannot have more of it.

- The pleasure that you have gotten disappears if it is temporary and upon losing it, leads you to duḥkha.

- Otherwise, if the desires are not fulfilled in the first place, that also directly leads to duḥkha.

All possibilities thus end in duḥkha finally. So, the cycle of life is an endless cycle of tṛṣṇā and duḥkha, according to the Buddha. If you look back and think, you do realize that this is indeed the case. We are never permanently satisfied with anything - we always eventually crave for more of anything that we desire. Modern biology too agrees with this - your sensitivity to the pleasure signal reduces with more exposure to it; and hence to get the same amount of pleasure, you end up desiring for more of the signal and you look for more of the stimulating object. Buddhism is a very empirical school of thought. So, in short, we desire eternal pleasure but we are not able to get it at all. Our life is tragically conspired in such a way that we have a deep desire to search for, seek and grasp onto persistent pleasures (that will never end) but we are also designed in such a way that we cannot get that at all. No pleasure is permanent or persistent or everlasting - it is in this sense that the word duḥkha needs to be understood - the transitory nature of pleasure.

Wait a minute - did you see that word again - persistent! Do you remember the last article in this series? Where the Upaniṣads proclaim that beneath the transitory flux of the phenomenal world, there is a persistent unchanging reality. And now Buddha says that a search for a persistent pleasure is doomed to fail. Buddha now transfers this impossibility of persistence of pleasure in the realm of feelings, to the entirety of metaphysics itself. There can’t be a persistent pleasure => there can’t be a persistent “anything”. Like the search for a persistent pleasure always ends in vain, he claims that the search for a persistent anything, including the Self, fails. Read further for elaboration.

Buddha shares some fundamentals with the ideas in the Upaniṣads. He did believe in saṃsāra - the endless cycle of life and death. He also espoused that the ultimate aim of anyone should be to liberate himself from this cycle. Buddha also believed that the phenomenal world of daily experience is transitory in nature and is in an ever-changing flux.

He however happened to disagree on two key things -

- the metaphysics &

- the method.

He disagreed with the metaphysics that there is an underlying unity that persists beneath this flux of the moving phenomena. He did not think that latching on to that constant - the ātman/ the sat/ the brahman - was the key to escape the cycle of life. He did not believe in any enduring self. That is why his philosophy is called anātman. Why did he say so? Buddha believes that the search for a deeper, persistent metaphysical reality is in vain and is nothing but a more sophisticated version of the desire to search for a persistent pleasure. Buddha finds the meditation by the Upaniṣadic sages on an unchanging self to just be a tad more sophisticated manifestation of the desire (tṛṣṇā) for persistence. The Upaniṣads propound that the self is so subtle, refined and beyond any dualistic modes of experience. Buddha goes one step further and says that the self is so subtle that it is not there at all! The search for the subtle self is in vain and is just a part of the cycle of tṛṣṇā - duḥkha. Instead of latching on to a persistent experience of pleasure, we are just now trying to latch on to a persistent ātman and it only fuels the cycle of samsara and hence will not lead to liberation at all - according to the Buddha. If not for the realization that we are ātman, what will give liberation from saṃsāra according to him?

Buddha thought that the key to liberation was to simply let go of the craving for anything permanent and accept the transitory nature of the world as such - realize that there is no enduring self, substance, or brahman and that everything is just simply flowing. That is why Buddha uses the term nirvāṇa (Pali: nibbāna) for liberation, [instead of mokṣa], which literally means “extinguishing” - in this context, extinguishing of the desire (tṛṣṇā).

The Three Jewels of Buddhism thus summarized are:

- Everything is unsatisfactory - duḥkha (Pali: dukkha)

- Everything is impermanent - anitya (Pali: anicca)

- Everything is insubstantial - anātman (Pali: anattā)

Catvāri Āryasatyāni: The Four Noble Truths

Buddhism is known for its concise formulae. The human condition is summarized by Buddha in the four noble truths which in Saṃskṛta is catvāri āryasatyāni (Pali: catur āriyasaccāni)

Noble Truth 1: Duḥkha || All phenomena are unsatisfactory.

The first noble truth is that all conditioned phenomena, whether physical or mental, including human lives are fleeting (anitya) and insubstantial (anātman). There are no enduring entities at all whatsoever. This entire world is a moving flux of events that is continuously changing with time. Selfhood, which is the existence of a persistent ātman that enables us to talk of a unified person through time, is all a fiction. Remember in the previous article where we argued that we all have a strong sense of “me” that is persistent, that enables us to say we are the same person as 10 years ago, even though everything observable about us has changed? Buddha says that that deep sense of personal identity that we have is basically a misunderstanding and an illusion that the fluxes of our thoughts impose on themselves. We constantly desire to cling to impermanent entities as if they were permanent and that is what leads us to duḥkha. The Upaniṣadic sages thought that the key to liberation from rebirth was realization of the stable principle within oneself that also happens to be the first principle of the cosmos and the divine. Buddha disagreed and said that enlightenment arises only when we realize that there is no stable persistent inner reality at the cosmic level, or the individual level, or the divine realm (no sat, no ātman, no brahman). There is no basis or substantiation for anything. The ephemeral fluxes of fleeting events is all there is.

Do you remember the four-fold argument for the justification for the existence of ātman that really constitutes who we are, and makes us the same person across the immense changes that we experience through life? Here, they are for your recap.

- Each of us has a persistent sense of “me”.

- This “me” (as is intuitively felt) must be unchanging.

- But personality, thoughts, behavior and bodies - and even whether we think or not - they all change.

- Hence, the persistent “me” (ātman) cannot include these elements.

Here, Buddha asks us to reject the very first statement - Each of us has a persistent sense of “me” - to be an illusion - no matter how strong that intuition is! All that is there to us is in the third statement - the continuously changing personalities, thoughts, behaviors and bodies. Traditionally, Early Buddhism categorizes these changing elements of our life into skandhas (Pali: khandhas), meaning: aggregates/heaps - Buddha says that all that we are is constituted of 5 skandhas - they are: our material body (rūpa), our feelings (vedanā), our perceptions (vijñāna), our conceptions (saṃjñā) and our inherited dispositions, will, character, habit, instincts etc.. (saṃskāra). All these 5 skandhas are changing. The Buddha says that these changing elements are all there is to you. In the Upaniṣads, if you remember, these phenomena in the skandhas are the ones that conceal and mask the fundamental ātman within - which is different from, yet is beneath and grounds, all these changing skandhas. But the Buddha says that there is nothing beyond these skandhas and all there is to a person, is this potpourri of the flowing states. In short, according to the Buddha, there is no difference between YOU and YOUR LIFE. YOU = YOUR LIFE. You are basically a bundle of what has happened, what is happening, and what will happen. There is nothing beyond these changing bundles of skandhas that holds all of these together and gives you a constant identity. There is nothing that owns these experiences and nothing TO WHOM these experiences happen!

Looking for an ātman, Buddha says, is due to self-interest, a form of desire that again traps you into the tṛṣṇā-duḥkha cycle. Real liberation is to accept that there is no self to us at all. We are just a pile of our material bodies, feelings, perceptions, conceptions and dispositions. There is nothing that holds the bundles of these five heaps together either at a given time or across times. Not that you should identify yourself with any of these individual skandhas or as an aggregate, but this would again represent attachment that leads to suffering. The fact that Gautama is the same person whether he is 10 years old or 50 years old is a fiction. Each moment of us is distinct. This thought process is called kṣaṇikavāda (momentariness) and one should perfectly understand and realize this.

Noble Truth 2: Avidyā || Ignorance is the root cause of unsatisfactoriness.

Given that life is transitory and unsatisfactory, what is the reason for it? Also, the Buddha denies that there is any persistent self and that we are not the same person who we were, a moment ago. Then, why do we feel such a strong sense of personal identity? Surely, this has to be explained. These are what are explained succinctly in the second noble truth of the Buddha. The Buddha tells us the root cause for the human condition that is presented in the first noble truth. It is: avidyā (Pali: avijjā) - ignorance of the actual state of affairs that leads to unenlightened actions motivated by tṛṣṇā (Pali: taṇhā). The thirst or craving (tṛṣṇā) is due to our egocentric mentality where we think we are an enduring self and hence we seek to extend our sphere of influence to dominate for selfish interests. In short, to get rid of selfishness, the Upaniṣads ask us to realize that your self is same as the self of everyone else and also same as the essence of the entire cosmos. Whereas Buddha, in order to get rid of selfishness, kills the self and says that there is no self to be selfish in the first place. The Buddha dissolves our ego into a fleeting bunch of momentary skandhas. There is no brahman either. The world is simply a fleeting bunch of phenomena.

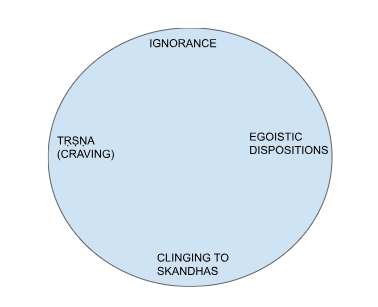

Buddha gives a naturalistic explanation of the human condition. Our ignorance makes us act by our inherited dispositions which makes us think that we have a self and gives us a sense of ego which makes us make to cling (upādāna) on and become emotionally attached to any of our skandhas (maybe a sense pleasure or a dogma or a ritual or a belief) which feeds our desire (tṛṣṇā) that only makes us become more and more ignorant and fuels our rebirth.

Noble Truth 3: Nirvāṇa || There is an end to suffering.

The third noble truth is that there is a way out of this endless cycle which is captured by the word nirvāṇa. This word literally means “blowing out” or “extinguishing”. Note that the choice of the word - nirvāṇa that means “blowing out / extinguishing” (rather than mokṣa) and the word tṛṣṇā that means “thirst” in a literal sense (rather than kāma) - is very significant. The word nirvāṇa contains the Sanskrit verb root vā from which we get words related to wind like vāyu or vāta. The word nirvāṇa hence literally means “blowing out”. Wind extinguishes fire. Also the word tṛṣṇā comes from the Sanskrit verb root tṛṣ which literally means thirsty, desirous of water and is cognate to the English word “thirst” through Proto-Indo-European. The root then semantically extends to mean anything excessively hot so that it needs water to be controlled or cooled. So, the word tarṣa can also mean “sun” and is derived from the same verb root tṛṣ. Why did the Buddha use specifically these words like tṛṣṇā (being hot like fire) and nirvāṇa (wind blowing out fire) that has connotations with fire and wind that put out fire? These fires are supposed to evoke in us, the reference to the fire that forms the central part of the Vedic sacrificial ritual. The Buddha taught that the vedic yajñas are absolutely unproductive and only fuel the cycle of desire and suffering. Hence, the choice of the word nirvāṇa that means blowing out of the fire (of desire) is a subtle reference to the vedic fire, which according to the Buddha, is not useful at all and only traps us in this saṃsāra. The fire of desire generates only more desire and experiences and expectations. This state of nirvāṇa wherein all cravings cease is the state of enlightenment. Like the Upaniṣads, the Buddha does not have anything to comment on what exactly happens in this enlightened state - it is only negatively described as the extinction of desires and ignorance. There is no personality left to experience this state as our ego is completely dissolved.

Noble Truth 4: Ārya Aṣṭāṅga Mārga || The Eightfold Path - Way out of Suffering.

The fourth noble truth is that there is a way out of suffering and into nirvāṇa. This is the eightfold path called in Sanskrit as āryāṣṭāṅgamārga (Pali: āriya aṭṭhāṅgika māgga).

They are:

- Right View - Samyak Dṛṣṭi (Pali. Sammā Diṭṭhi) Understanding the four noble truths, and remembering that our actions have consequences.

- Right Intention - Samyak Saṅkalpa (Pali. Sammā Saṅkappa) Avoiding any thoughts that reinforce our ego and being in the present moment without getting carried away by any of our skandhas, simply observing our thoughts as they are.

- Right Speech - Samyak Vāk (Pali. Sammā Vācā) Refraining from unnecessary and harmful speech like lying, gossiping, slandering etc.. as they reinforce our ego.

- Right Action - Samyak Karmānta (Pali. Sammā kammanta) Refraining from physical actions that perpetuate our self interest like violence. Leading a moral and pious life without seeing others as means to satisfy our ego.

- Right Livelihood - Samyak Ājīva (Pali. Sammā Ājīva) A livelihood that is virtuous and non-harmful to others, that avoids indulgence and extreme asceticism.

- Right Effort - Samyak Vyāyāma (Pali. Sammā Vāyāma) Avoiding unwholesome states of mind and being always vigilant, thereby overcoming dullness.

- Right Thinking - Samyak Smṛti (Pali. Sammā Sati) Awareness to see things as they are, without getting trapped down by any of our skandhas.

- Right Concentration - Samyak Samādh (Pali. Sammā Samādhi) Single-pointed meditation that leads one to enlightenment.

Pratītyasamutpāda: Dependent Origination - Buddhist Metaphysics

The Buddha has said that there is no independent, persistent self. But if we take this view to its fullest logical conclusion, there are several puzzling questions that arise:

- If there is no “me” and it is an illusion, then what causes this sense of “me” and what makes me intuitively think that I am the same person as I was a decade ago?

- If all there is to me is just my thoughts, who is experiencing them? What creates the notion of the subject?

- How is reincarnation and karma possible without a sense of self? What is it that connects me in this life to my next life?

- If the person I am right now is not the same as the person I will be a few hours later, then how is morality and karma justified? If I commit an immoral act now, and am made to suffer for its consequences later, why am I punished - as the person who did the action and the person who is receiving the punishment are not the same person, as they exist at different times? In other words, if Rama Seshan now, is not the same person as Rama Seshan 10 years later (there is no enduring self of Rama Seshan), then why should Rama Seshan 10 years from now suffer the consequences of actions done by Rama Seshan now?

- Why should Rama Seshan work now for his enlightenment, if the person who is going to attain enlightenment will not be the same person as the one who is Rama Seshan now?!

All these questions are attempted to be answered by the Buddha through his master metaphysical theory - the theory of dependent origination, known in Sanskrit as pratītyasamutpāda (Pali: paṭiccasamuppāda).

Let’s answer the above questions one by one. First, if I think of something, who is thinking of it? If I see something, who is seeing it? What is the subject for all my experiences? How can Buddha explain the subjectivity of our experience when he denies the enduring subject? He says that it is in the nature of thoughts to be self-conscious of themselves - i.e. each discrete perception at any given moment is its own perceiver, each discrete thought at any given moment is its own thinker, each discrete sight at any given moment is its own seer, each discrete memory at any given moment is its own rememberer. Intrinsically self-aware subjectless thoughts are thinking themselves. There is a life trajectory and history but there is no subject of that history distinct from the momentary skandhas themselves. Consciousness is reduced and deconstructed into being a momentary natural property of each momentary skandha and not a constant that is distinct from them and grounds them separately.

If consciousness is momentary, what makes me feel that I am enduring as a person throughout my life? Again, answering this, the Buddha says that just because there is no enduring self that stays constant and serves as the subject for all of our skandhas, that does not mean that all our skandhas are just random disconnected heaps. There is a connection that runs through them and connects the skandhas at one moment to the skandhas at the next moment. This is nothing but causal continuity. Remember the argument about the identity of the ship of Theseus that we discussed in the last article? We saw that causal continuity from the initial ship of Theseus is what enables the persistence of the identity of the ship of Theseus even as its parts are gradually changed. Similarly, the Buddha says that each skandhas of this moment are causally interconnected to the skandhas at the previous moment and the skandhas of the next moment. The skandhas at each moment is caused by the skandhas at the previous moment and causes the skandha that will be at the next moment. Intrinsically self-aware subjectless thoughts are thinking themselves and other thoughts due to this causal continuity. These intrinsic subjectless thoughts that are thinking themselves and each other do not need a grounding in a persistent subject. They form a continuity by knowing their immediate predecessors and causing their successors. To put in the simple words of the modern American pragmatist philosopher William James,

Each pulse of cognitive consciousness, each thought dies away and is replaced by another. The another, (among the other things it knows), knows its own predecessor saying that “thou art mine and part of the same self with me”. Each later thought, knowing thus all the thoughts which went before, is the final receptacle of all that they contain and own. Each thought is thus born as an owner and dies unowned, transmitting whatever it owned (awareness of previous thoughts) to its own later proprietor. (That is, each instantaneous thought is the subject that is aware of itself and all the other thoughts that came before. At the next moment, this thought vanishes and imprints itself on the next thought of the next moment as its memories).

To give an easy analogy - it is like what we see in a family tree. The father earns money at his own generational lifespan and transfers his inherited earnings and his inheritance (from his ancestors) to his son in the next generation who now earns and owns his own earnings as well as his inheritance from his father. There is no single person that owns all the money in the family tree together across all generations. Every person owns his ancestral inheritance and his own earnings. He dies and passes it to his son who not only owns his own earnings but also the inheritance from his father. There is no single person who owns all the money together. Similarly, each thought is aware of itself and its preceding thoughts (owns itself and its predecessors). Then, it passes it on as a memory to the succeeding thought that is not only aware of itself but its inherited thoughts as well.

What is being propounded here is that the interactions of the momentary thoughts, the perceptions in our skandhas, the causal continuity between the skandhas of a given moment, and the skandhas of its successive moment; together with the intrinsic nature of awareness in our thoughts and perceptions, of the thoughts and perceptions, and of their predecessors - this is what is illusorily perceived as an enduring subject, as a receptacle of all the skandhas together, looking out on the world from a privileged point of view. The intrinsic awareness of some skandhas (perception, thought, etc..) at the present moment - awareness about their corresponding skandhas of all the preceding moments - is merely a consequence of causal continuity between them and their intrinsic awareness of what came before them. This is ephemeral. So, the term “person” according to Buddha is just a convenient shorthand for referring to a causally connected stream of skandhas. So, we are basically a causally evolving continuous stream of events in our skandhas, like a long row of dominoes toppling successive pieces. The current domino is not the same domino as the one that fell an hour ago, but they are related in the sense that the movement of that earlier one led to the toppling of this current one.

But what exactly is the mechanism that connects a person causally to his next birth? That seems like a tough nut to crack. Have this at the back of your mind.

Similarly, the Buddha says that causal continuity is sufficient to account for karma and reincarnation - the person who you will be at next birth is causally connected to you in this birth (although how exactly it is so, is a mystery). It is just that the person who you will be in the next birth will not inherit the memories of your thoughts in this birth. Causal continuity still exists between your skandhas of this birth and the skandhas of this next birth, but awareness of each skandha for all of its predecessors is cut down in this process of reincarnation.

A metaphor given by the Buddha is that it is like a candle lighting another candle and blowing itself out. The fire at the lighted candle is causally derived from the fire of the candle that lit it, even though it itself blew out after creating the fire of the candle that has been lit now. So, causal continuity is enough to ensure that consequences follow actions. Therefore according to Buddha: we are reborn in every moment, we are a new entity succeeding the past entity, and shaped by the laws of karma. This process continues even as the so-called “person” experiences a physical death; the matter part of the skandhas comprising of his body and the mental events comprising his consciousness casually continue, they just don’t continue together. When the non-bodily skandhas become associated with a new continuum of matter, we conventionally say that the “person” has been “reborn”. In reality, it’s simply another temporary association in flux with time, still lacking any kind of enduring quality or aspect.

OK, so now we have justified why there is a sense of a persisting subject and how karma and reincarnation work without an enduring subject. But still, there is the crucial question of motivation for moral action - why should I be interested in my future if I won’t be the same person as I am now? This is the one that is the toughest to tackle in this framework. The Buddha still believed that moral responsibility should be there even in the absence of a permanent self and we should be concerned about our future skandhas, even if they are not ours. Also, why should I be compassionate and what can justify altruism in this framework? If I do not even need to worry about the consequences of my own actions now on my own future (because there is no “me”), then why should I even bother being compassionate to others?

The Buddhist tradition has it that Buddha left many such questions unanswered. There are four popular questions, which tradition has it that the Buddha refused to answer or elaborate - they are called the four unanswerables, referred to in Pali as acinteyya.

They are:

- What happens after enlightenment?

- What powers does one attain when absorbed in dhyāna (Pali: jhāna)?

- What is the precise working mechanism and motivation of morality and reincarnation through karma (in the absence of an enduring self)?

- What are the origins of the cosmos?

The Buddhist tradition also has lists of many other unanswered questions by other names. Buddhism will get into a lot of trouble with these notorious questions, although Buddha himself discouraged philosophizing on these questions. Buddha defended his refusal to answer tough questions like these by giving two excuses. One is that these questions again are a part of the trap that leads us to attachment, and traps us in the cycle of rebirth. The analogy given is as follows: If a person is struck by a poisonous arrow, he should only focus on getting rid of it as soon as possible, and not ponder such things as who threw the arrow, what is the jāti of the man who threw the arrow, who is the maker of the arrow, and so on. Similarly, for the Budha, focusing on these unanswerable questions is like pondering about the arrow. The urgent aim is to get rid of suffering. The next way in which Buddha dodged overly philosophical and controversial questions is by saying that his teachings, like everything else, were also not persistently true and were just conditionally true, merely serving as a ladder that needs to be discarded after one attains the heights of enlightenment. Pondering on the deficiencies of his theory would only lead to more clinging onto our thoughts, and trap us in saṃsāra. This appears to convey that the teachings of the Buddha are only instrumentally valuable in getting us where we want to go, and only for that reason. This means that it makes no difference whether it is even true ontologically or logically water-tight. Beliefs don’t have to be true to be useful (just as parents lie a lot to their children to have them believe a lie and make them do something!). This compares in Western philosophy to Wittgenstein, who urged his reader to see his philosophical work Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, as a ladder that can be thrown away once the reader has attained a full understanding of his philosophy. Philosophy is, according to this viewpoint, a means to end suffering, and not a quest for truth or knowledge for the sake of it.

In the last article, we saw that the Upaniṣads (alone) do not exactly answer what is the relation between the phenomenal world of multiplicities and the underlying world of unity, and also does not give a clear picture of what exactly is the same in equating the underlying world of all selfs, gods, and the cosmos. Now, the Buddha also leaves some questions unanswered.

Later, both Hinduism and Buddhism will split in the classical era of the sūtras and darśanas. They each split into several schools, vehemently arguing with each other, depending on how they attempt to answer these questions. Let’s leave some questions for the forthcoming generations to answer - right?! We will see the various darśanas in Hinduism and Buddhism scratching their heads over these questions. Until then, thanks for reading, see you in the next part with another interesting philosophical tidbit!

Read the next part in this series here.

References

- The Principles of Psychology, Vol 1, p.339.