Veer Savarkar - Transportation for Life, Transcending From a Man to an Idea

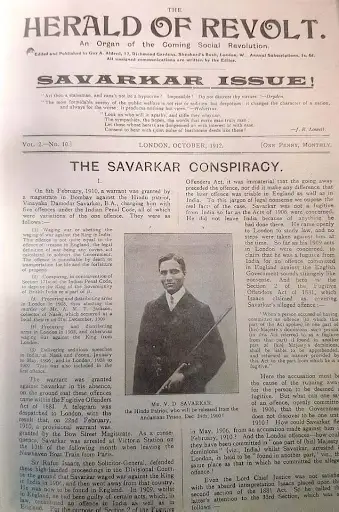

28 December, 2024

4408 words

share this article

This is part 3 in a series on Veer Savarkar. Read Part 1 and Part 2.

कृष्णाय वासुदेवाय हरये परमात्मने | प्रणतः क्लेशनाशाय गोविंदाय नमोस्तुते ||

Kṛṣnāya vāsudevāya haraye paramātmane | praṇataḥ kleśnāśāya govindāya namostute ||

In the suffocating darkness of British captivity, where hope was but a faint whisper and death loomed large, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, the indomitable revolutionary, found solace in the eternal words his brother had once shared. The śloka echoed in his mind. Savarkar, the crown jewel of India’s freedom struggle, had fallen into the iron clutches of the colonial masters. Dragged to their headquarters, he stood unbowed as the British, cloaked in a hollow display of authority, declared his fate. The sentence was a verdict of suffering—a future shackled in chains, shadowed by torment, and ever so close to the gallows.

Yet, even as their words thundered with the weight of cruelty, Veer Savarkar’s spirit clung to the timeless essence of the śloka. In Kṛṣṇa, he found not only a protector but a reminder of dharma—the unyielding resolve to rise above despair. In Govinda, he saw the strength to face pain, to transcend mortal trials for a cause far greater than himself.

As the street police escorted him to his destiny, he bore with him not fear, but the undying spirit of his people and the unwavering values of his civilization. He knew death or something worse awaited him, but death was merely another battle to fight and conquer. To steady his soul and steel his resolve, he recited to himself the hymn of truth, courage, and transcendence:

What fear of death? For I am not the body but the soul.

My goal is the light—history, truth, and honor.

This divine fire shall consume all falsehoods,

Let this body perish for the cause of truth.

Even in chains, Savarkar’s voice carried the strength of a lion, echoing through the walls of his cell and the hearts of his countrymen. His imprisonment was not a submission, but a crucible that forged him into an unyielding force. To sow the seeds of revolution in one’s homeland, surrounded by shared hopes and communal fervor, is a challenge, but one buoyed by support and solidarity. Yet, to nurture rebellion in the treacherous isolation of a foreign prison, to keep the flames of freedom alive in the brutal void of Kālā Pāni, demanded courage beyond imagination.

In this part of our series, we delve deeper into how this man turned chains into weapons, exile into resolve, and suffering into the sacred fire of revolution. Svātantravīra Savarkar, though confined within the oppressive walls of the Andaman Cellular Jail, transformed his pain into purpose and his captivity into a battlefield for freedom. His indomitable spirit burned brighter than ever, forging ideas and actions to inspire future revolutionaries. We shall now delve into the detailed chronology of events as they unfolded.

At Brixton Prison

From Bow Street Police Station, he was transferred to Brixton Prison, where Guy Aldred, a British publisher of Shyamji Krishna Varma’s banned Indian Sociologist, was also serving a sentence. Aldred held the distinction of being the first British citizen imprisoned for supporting Indian independence!

The British authorities had begun planning Savarkar’s extradition to India shortly after his arrest in London. A letter dated 26 March 1910 from Assistant Police Inspector Guyder to Deputy Superintendent C.I.D. Charles John Power outlined the mission. Power, accompanied by three police jamadars—Amarsingh Sakharamsingh Pardeshi (a former member of Savarkar’s secret society Mitra Mela), Muhammad Sadiq, and Usman Khan—was tasked with serving the arrest warrant issued on 8 February 1910. Interestingly, one of the officers, Usman Khan, passed away after reaching London, adding an eerie twist to the unfolding drama.

Savarkar was visited by his compatriots such as V.V.S. Aiyar, Niranjan Pal, Virendranath Chattopadhyay, and Desmond Garnett. Efforts were made to hold Savarkar’s trial in London. Two plans were also drawn up to free Savarkar with the help of Irish revolutionaries, but fate was not in their favor. Savarkar gave V.V.S. Aiyar a cryptic message-

While heading to Hindustan, the ship will halt at Marseille Port…

Savarkar, however, remained remarkably composed in prison. When his associate Niranjan Pal questioned why he knowingly courted arrest against the advice of his comrades, Savarkar’s response was resolute- “I came to London to be arrested because my shoulders are broad enough to bear the consequences.” This unshakable spirit was also found in his immortal Marathi poem Maazhe Mrityupatra (My Last Testament), written in Brixton Jail and dedicated to his sister-in-law Yashodabai (Yesuvahini).

Even behind bars, Savarkar’s revolutionary zeal was undeterred. When his associate V.V.S. Aiyar visited him, Savarkar urged him to continue the fight for India’s freedom, showing that even imprisonment could not chain his unwavering commitment to the cause. His actions and words transformed his incarceration into yet another battlefield in the larger struggle for independence.

The Famous Leap at Marseille

Savarkar’s audacious leap into the cold waters off the coast of Marseilles on 8th July 1910 marked a defining moment in the saga of India’s struggle for freedom. This bold act of defiance not only showcased his indomitable spirit but also etched his name into the annals of global revolutionary history. It was no ordinary escape attempt—it was a statement that reverberated far beyond the confines of colonial power.

What followed was nothing short of extraordinary. Savarkar’s daring escape and subsequent arrest on French soil sparked an international legal battle that gripped the world’s attention. Dubbed ”The Savarkar Case” or L’affaire Savarkar by British and French chroniclers, the episode unfolded as a high-stakes drama at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, the precursor to today’s International Court of Justice. This was not merely a trial about jurisdiction or extradition; it was a battle of ideals that put the question of India’s sovereignty and the legitimacy of British colonial rule under international scrutiny.

The saga began aboard the S.S. Morea on 1st July 1910, as Savarkar was being transported from Britain to India under heavy surveillance. His leap into the sea at Marseilles, his brief moment of freedom on French soil, and the ensuing diplomatic storm culminated in the tribunal’s award on 24th February 1911. This legal and political whirlwind thrust the issue of India’s freedom onto the international stage, forcing the world to confront the simmering discontent in the colonies.

Trials in India

On September 15, 1910, his trial began in India before a special tribunal convened by the British colonial authorities. Three separate cases were brought against him. In the first, Savarkar stood among thirty-eight accused; in the second, the focus narrowed to him and Gopal Patankar, charged with seizing Browning pistols. Recognizing the gravity of the situation, Savarkar addressed his co-accused with a selfless plea- “Put all the burden on me and try to escape.”

After sixty-eight days of arduous days of proceedings, the verdict came on December 24, 1910. Savarkar was sentenced to life imprisonment and dispatched to the dreaded Cellular Jail in the Andaman Islands, infamously known as Kālā Pāni—a penal colony synonymous with suffering and despair. While some of his co-accused managed to escape, others faced varying degrees of punishment. Among them was his younger brother, Narayanrao Savarkar, sentenced to six months of rigorous imprisonment.

The British, however, were not content with merely silencing Savarkar through a single sentence. They launched a second trial, leveling additional accusations against him. This trial began on January 23, 1911, and concluded with ruthless efficiency just a week later, on January 30, 1911. Once again, Savarkar was condemned to a second life term in Kālā Pāni. During one of her visits to the dreaded Kālā Pāni, Mai Savarkar, the devoted wife of Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, could not conceal her anguish. Witnessing her husband endure such a harsh punishment, she expressed her concern, her heart heavy with yearning for a semblance of a normal life—a life of shared joys, raising children, and building a home together.

Savarkar, with his unyielding resolve, sought to console her, his voice calm yet infused with profound conviction. He said-

If you are ever tempted by the idea of a normal married life—a life where we raise children, gather sticks and stones to build a home—think instead of the sacrifice that paves the way for a national life. This life, Mai, is not ours alone. It is for the countless generations yet to come, who will breathe the air of freedom because of the hardships we endure today. Your sacrifice, like mine, will nourish the soil of our motherland, giving rise to a future where thousands will prosper.

His words were a testament to the extraordinary strength required not only of those who fought for freedom but also of their families, who bore the silent burden of their sacrifices. The struggles of mothers, fathers, wives, and children of this dharmayoddhās remain an indelible part of India’s journey to independence. Their silent courage and selflessness, though often overshadowed, are an enduring reminder of the collective cost of freedom—a freedom we must cherish with a deep sense of indebtedness and honor.

Mai Savarkar’s grief, transformed by her husband’s words, became a quiet resolve—a symbol of the sacrifices borne by countless families in service of a greater cause. Their sacrifices were not just personal but civilizational, the bedrock upon which the edifice of India’s liberty was built.

50 Years of Life Imprisonment

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, sentenced to an unprecedented fifty years of life imprisonment, faced an ordeal designed to crush even the strongest of spirits. Yet, for Tatyarao, as he was fondly known, the chains of Kālā Pāni became the inkpot of his unbroken resolve. Viewing this punishment not as an end but as an opportunity, Savarkar turned to his first love, literature, and set his mind to explore his literary dreams amidst the confines of the Cellular Jail.

Such was the indomitable spirit of this literary genius that even in the desolation of imprisonment, his creativity thrived. He began with a poetic dedication to the warrior-saint Guru Gobind Singh Ji, drawing inspiration from the Sikh leader’s valor, sacrifice, and unwavering commitment to righteousness.

Following the trials, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar was transferred to Byculla Jail from the transit jail at Dongri, marking the beginning of his journey into the abyss of colonial retribution. From Byculla, he was moved to Chennai, where arrangements were made for his transport to the Andaman Islands aboard the British vessel S.S. Maharaja.

Stripped of his dignity, he was made to wear coarse prisoner clothing and subjected to the constant torment of iron chains that bound him day and night. His identity was reduced to a mere number—32778—a stark reminder of the dehumanizing tactics of the colonial regime. Branded D for Dangerous, Savarkar was considered too great a threat to the British Empire, his unrelenting spirit and revolutionary ideals warranting the harshest of punishments.

Aboard the S.S. Maharaja, he was kept under strict surveillance, his chains clinking ominously with every step as if a cruel overture to the horrors awaiting him. He writes- “Climbing into that steamer to be transported for life was like putting a man in his coffin…I was being put on my funeral pyre. The only difference was that I felt what was happening to me while my corpse would have felt nothing.”

The Kālā Pāni journey was meant to break him, but for Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, it became a crucible of resilience. Shackled with fifty of the most hardened criminals—men hardened by lives steeped in filth, cruelty, and crime, some even ravaged by foul diseases—Savarkar found himself sharing an “iron cage” where every inch of space was a battlefield.

In this stifling space, there was no scope even to stretch. The bedding was so compactly done that Savarkar wrote, ”My feet touched their heads, and their feet came up near my mouth. If I turned on the other side, I found that a mouth nearly touched my mouth.”

With bronchitis, Savarkar was allocated the one seat with a sliver of air—a corner near two foul-smelling casks used as chamber pots. But this was no privilege. The smell was overwhelming and when Savarkar came to his corner, one of the convicts was already relieving himself.

Despite his unbearable circumstances, Veer Savarkar’s humanity and sense of dignity remained intact. Seeing him approach, the convict hesitated, ashamed, and prepared to leave unfinished. But Savarkar stopped him with a calm, empathetic voice-

The claims of the body cannot be put off. There is no shame in answering the call of nature. In a moment, I may follow you. Do it freely. We cannot help it. We cannot afford to feel ashamed in this wretched condition. I can smell, so you think, but do you not have a nose too? Why then should I feel the stink any more than you do?

Another prisoner, taking pity on Savarkar’s composed demeanor, was willing to exchange places with him, suffering the worst stench. But Savarkar was not willing. ”Why should I put you in the midst of dirt by exchanging my place with yours? I also must inure myself to this kind of life.” This moment of unseasoned generosity among men that society had pronounced irredeemable left Savarkar deeply moved. Reflecting on the incident, he wrote-

My heart melted when I heard this. His generous offer was a wonder to me. I said, ‘O my God, even in the hearts of the most sinful ones, thou makest thy abode, turning it into a shrine of worship and prayer. Thou turnest what is dirty and untouchable into the holiest of the holy—the sacred basil pot it becomes when it is no more than a sink of filth and crime.

The four-day journey to Andamans was indescribable in its misery. However, the physical ordeal was minuscule before the tribulations Savarkar had undergone for the past year. The British were unleashing all the weapons so that they might break him.

There was the fabricated warrant issued for his arrest; his voluntary return to London from the safety of Paris, knowing capture awaited him; the bending of Britain’s laws to execute that warrant; his dramatic escape in Marseilles, followed by his recapture aboard the S.S. Morea; the humiliating journey under the watchful eyes of officers simmering with rage at his daring; the farcical trials on Indian soil, where the outcome was a foregone conclusion; and finally, the unheard-of sentence of fifty years of transportation to the hellscape of Kālā Pāni.

Kālā Pāni

He was destined for the hellscape of Kālā Pāni, the Cellular Jail in the Andaman Islands, infamous for its inhuman conditions and the despair it inflicted on political prisoners. At first, the island of Andaman looked beautiful with its line of coconut trees and lush greenery uphill inside a fortified wall lay the infamous Cellular Jail. When Vinayak Damodar Savarkar disembarked at Port Blair, the grim specter of the infamous Kālā Pāni loomed over him. Yet, even as chains clinked with every movement and the oppressive heat weighed heavily on him, his mind raced ahead, as always, to the idea of a greater India.

Standing on the wharf, waiting for his turn to be led into the dreaded Cellular Jail, inspiration struck him. The strategic location of the Andaman Islands in the Bay of Bengal revealed itself to him in a flash of brilliance. He later wrote-

It suddenly struck me that the islands were so located in the Bay of Bengal that they constituted the bastion in the naval fortification of India from the East. As such they had an abiding importance in the future defense of our country… . We must turn this base of defense into a naval fortress, not unlike the formidable Sindhu Durga in the glorious days of Shivaji.

Even in chains, Savarkar’s thoughts were of India’s future—a free nation with a formidable navy, guarding her shores. But his dream was short-lived. A guard barked orders, pulling him back to the grim reality of his existence.

He stood, gathering his bedding on his head and clutching his pots and pans in one hand. With his chains girded tightly around his waist, he prepared to follow his captors. The transition from dream to reality was sharp and jarring. He described the moment vividly-

The mind suffers pain like the body hurled suddenly from a great steep height into the deep valley below. Disillusioned, and consigning to the future the glorious picture I had drawn, I stood up to face the grim reality of the present.

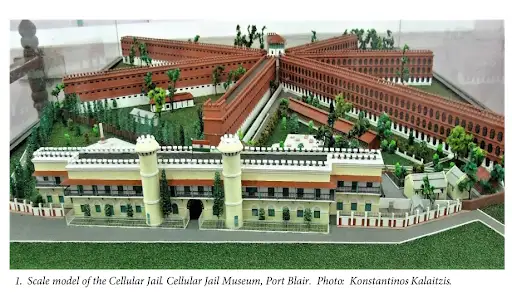

Savarkar was led up a steep ascent toward the gates of the Cellular Jail. Barefoot and weighed down by chains, every step was agony. The climb seemed interminable, and the iron clanking of his chains was a cruel reminder of his subjugation. At last, they reached the summit, and the ominous gates of the “Silver Jail”—as the Cellular Jail was mockingly named—came into view. The gates creaked open, and with a heavy heart, Savarkar stepped inside. He later reflected- ”I went in, and it was shut behind me. I felt that I had entered the jaws of death.”

And death it was, in every way that mattered.

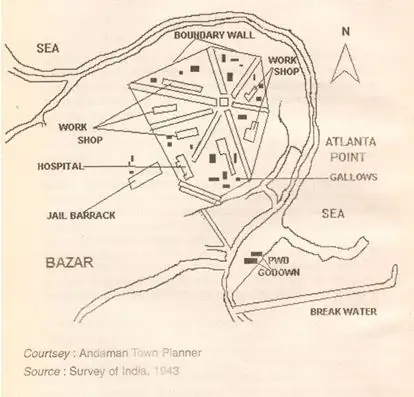

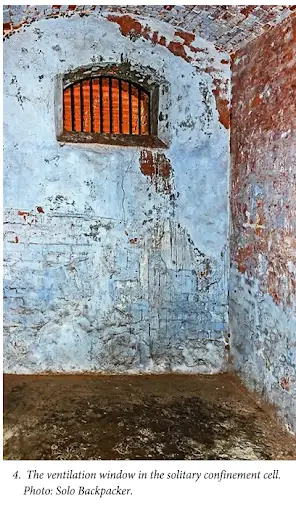

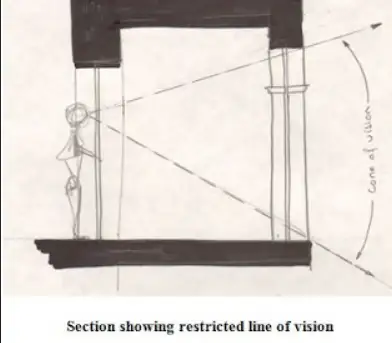

The Cellular Jail was a diabolical masterpiece of British colonial rule, designed to crush the spirit of its inmates. Built to house 600 convicts in utter isolation, its very architecture was a weapon of psychological and physical torment. The goal was not rehabilitation but the complete annihilation of resistance. The authorities believed that no man, however hardened, could last more than six months within its walls.

For political prisoners like Savarkar, the conditions were nothing short of hellish. Filthy and unhygienic surroundings bred disease and despair. Daily beatings and insults stripped away human dignity. The unrelenting hard labor—grinding oil or breaking stones under the harsh tropical sun—pushed even the strongest to the brink of collapse.

Among the tormentors of the Cellular Jail, few were as cruel and sadistic as David Barrie, the jailer. A man devoid of empathy, Bari denied the inmates even the smallest semblance of humanity. To him, they were not freedom fighters or political prisoners but mere criminals, no different from the thieves and murderers they were confined with.

The political prisoners, many of whom hailed from Bengal, were initially derisively labeled as “Bangalees.” Later, as revolutionaries from Punjab joined their ranks, they became known as “Bombwalahs,” thanks to their association with bomb-making activities. Those deemed particularly “dangerous” were branded with a dreaded “D” on their jail tags—a mark of infamy that reflected their indomitable spirit rather than any crime.

The conditions in the jail rivaled the horrors of Nazi concentration camps of a later era. Solitary confinement stripped prisoners of their sanity. The food, prepared in the filthiest of conditions, was barely edible. Worse still was the torment inflicted by sadistic wardens like Mirza Khan, also known as Junior Bari. Punishments were meted out without reason—whipping, bludgeoning, relentless beatings, and forced conversions to Islam.

Work in the jail was designed to break both body and spirit. Prisoners were forced to beat coconut shells with wooden hammers until the fibers softened for fabric production, a task as tedious as it was grueling. Even more excruciating was the Kohlu, a wooden press where inmates had to grind coconuts or mustard seeds, pushing a massive wheel by hand. The quota was brutal—30 pounds or 16 liters of oil per day. Those who failed were whipped mercilessly and made to continue until they met the target.

In their bid to save money, the British made prisoners pull carts, hauling goods or even officers as though they were beasts of burden. It was dehumanizing work that pushed even the strongest to the edge of collapse.

In the suffocating darkness of his cell, Veer Savarkar stood at the precipice of despair being kept in solitary confinement for six months, being handcuffed to a wall, and kept standing for seven days as a note from another prisoner was found in his cell being beaten and put on the oil press for 12 to 18 hours.

His body, broken by relentless labor and unyielding punishments, seemed like a hollow vessel, unworthy of further suffering. His mind whispered insidious temptation- ”End it now, Vinayak. Why prolong this agony? Is this existence not worse than death?”

But as the abyss threatened to consume him, another voice emerged—calm, resolute, and fiercely defiant. It spoke not with words but with the fiery conviction of his soul-

To toil for endless hours, even unto death, is not a waste. Even if you die nameless in this black cell, unknown and unrecognized, your sacrifice will be part of the great yajna of freedom. The countless lives given for this cause will not be forgotten, nor will yours. Do you want to die like a dog, taking your own life? What the British could not break, why give them the satisfaction of seeing you fall by your hand? No, Vinayak! You are a soldier in a sacred war. If you must die, die for that war. Die for that army. Die for Bharatmata.

This clarity struck him like a thunderbolt, shattering the oppressive weight of his despair. What was a mere body compared to the vast ocean of the freedom struggle? His torment became a small price to pay for the inspiration it might offer to future generations.

Savarkar not only clawed his way back from the brink of suicide but transformed this newfound strength into a beacon of hope for others. In the days to come, as his fellow inmates struggled under the same crushing despair, he became their anchor.

He would remind them of the greater war they were fighting, urging them not to let the British—or their despair—win. He recounted his revelation, saying- ”If we surrender to the darkness, we give the British exactly what they want—to see us defeated in body and spirit. Let us endure, let us fight. For every breath we take, for every drop of sweat we shed, we weaken their hold on our motherland.”

This indomitable spirit became contagious. Savarkar’s words rekindled hope in countless prisoners, pulling them back from the edge of suicide and inspiring them to endure the unendurable. In the hellscape of the Cellular Jail, where even the strongest souls faltered, Veer Savarkar’s unwavering resolve turned despair into defiance, proving that the light of freedom could never be extinguished.

Meeting Babarao

The reunion of Veer Savarkar with his elder brother Babarao Savarkar in the dreaded Cellular Jail of Kālā Pāni was a poignant moment etched with despair and an unyielding resolve. Babarao, who had been incarcerated there since 1909, had endured unimaginable torment, his only solace being the hope that his younger brother Vinayak was carrying forward the cause of India’s freedom from the outside world. The sight of Vinayak in the same inhumane surroundings shattered that hope in an instant.

When Vinayak arrived at the Cellular Jail, his heart yearned to see his elder brother, who had been his protector and guide through life. Babarao was to Vinayak what the steadfast Sahyādrī mountains are to the plains below—a source of strength, unwavering and nurturing. However, Vinayak’s inquiries about Babarao met with stony indifference from the prison authorities. Even Barrie, the sadistic jailer, dismissed him with contempt, warning him not to concern himself with other “criminals.”

Fate, however, had its plans. During a routine roll call where prisoners were assigned their daily tasks, the two brothers caught a fleeting glimpse of each other. Babarao, seeing his beloved younger brother in the tattered garb of a prisoner, let out an involuntary gasp of pain, “Tatya, how come you are here?” The anguish in his voice cut through Vinayak like a blade. To Babarao, Vinayak had symbolized the hope of their shared cause, a beacon of light fighting for Hindustan’s freedom from afar. Now, that beacon seemed dimmed, locked away in the same abyss of torment.

Before they could exchange more than a few words, the petty officer intervened, fearing Barrie’s wrath. The brothers were pulled apart, their brief moment of reunion tinged with unspoken words and overwhelming sorrow. Later, Babarao managed to send Vinayak a secret letter, pouring out the anguish of his heart.

Your dharma was to stay outside and fight for the freedom of Hindusthan. On that one hope, I was enduring all this torment. Vinayak, what will happen to our cause now? What will happen to Bal? I feel as though I will wake up and find this is all just a nightmare. Oh, my dear brother, why have you come here?

The letter was a crushing reminder of the weight of their shared mission and the unbearable sacrifices they had to endure. But for these brothers, surrendering to despair was never an option. They saw in their suffering the burning away of worldly and spiritual desires, leaving behind only the ashes of detachment and purpose. These ashes, smeared upon their spirits, became their armor against the relentless torment.

Vinayak resolved to transform this shared agony into strength. The brothers, though separated by walls and chains, found unity in their unyielding determination to keep the flame of freedom alive. Their bond, forged in love and sacrifice, became a symbol of resistance—a testament to their indomitable will to fight for the liberation of their motherland.

In his poetic self he wrote:

सारथी जिचा अभिमानी। कृष्णाजी आणि राम सेनानी ।। अशि तीस कोटी तव सेना । ती अम्हांविना थांबेना ॥

When She has a charioteer in Krishna and a Leader in Ram, with her thirty crore children her struggle shall never stop.

More in the next part of this series.