share this article

In the name of God,

In the name of Bharat Mata,

In the name of all the Martyrs that have shed their blood for Bharat Mata, By the Love, innate in all men and women, that I bear to the land of my birth, wherein lie the sacred ashes of my forefathers, and which is the cradle of my children, by the tears of Hindi Mothers for their children whom the Foreigner has enslaved, imprisoned, tortured, and killed, I, … convinced that without Absolute Political Independence or Swarajya my country can never rise to the exalted position among the nations of the earth which is Her due, And also convinced that that Swarajya can never be attained except by the waging of a bloody and relentless war against the Foreigner, Solemnly and sincerely Swear that I shall from this moment do everything in my power to fight for Independence and place the Lotus Crown of Swaraj on the head of my Mother; And with this object, I join the Abhinav Bharat, the revolutionary Society of all Hindusthan, and swear that I shall ever be true and faithful to this my solemn Oath and that I shall obey the orders of this body; If I betray the whole or any part of this solemn Oath, or if I betray this body or any other body working with a similar object, May I be doomed to the fate of a perjurer!1

As Kesavananda inscribed his commitment to Abhinav Bharat aboard the SS Persia, he heralded the inception of a clandestine society inspired by Giuseppe Mazzini’s ‘Young Italy’. This momentous act marked the commencement of Veervaar Svatantryaveer Savarkar’s strategically significant tenure in London, vividly captured in his narrative, ‘Inside The Enemy Camp’. Previously, we have traversed the early chapters of Savarkar’s life, one which was steeped in the cultural and spiritual milieu of a devout Chitpavan Brahmin household. Born to Śrī Damodarpant and Smt. Radhabai, young Vinayak was cradled in an environment rich with the echoes of Vedic chants and philosophical discourses from Rāmāyaṇa and Mahābhārata, which shaped the contours of his soul and intellect.

From his formative years, Savarkar was not merely a participant in his cultural legacy; but a vibrant prodigy who displayed an acute grasp of complex ideologies, and a profound ability to articulate them with clarity and passion. These early experiences were not just foundational; but they were transformative, imbuing him with a fierce resolve and a visionary outlook that would later define his revolutionary endeavors.

Savarkar’s journey from a scholarly youth to a revolutionary strategist was a testament to both his indomitable will and the rich legacy of cultural and intellectual inheritance provided by the Savarkar family. In the shadow of the Aṣṭabhuja Devī, young Savarkar solemnly pledged an oath that marked a turning point in his life. This vow came in the wake of the profound impact left by the execution of the Chaphekar brothers in 1897, whose sacrifice ignited a fierce resolve within him. Motivated by this climacteric event, Savarkar founded the Mitra Mela during his education in Nashik - which later evolved into Abhinav Bharat, the organization to which the earlier mentioned oath belongs.

Influenced by the impassioned rhetoric and daring actions of extremist leader Lokamānya Balgangadhar Tilak, and inspired by the intellectual prowess of ‘Kal karte’ Shivram Madhav Paranjape, Savarkar’s path was profoundly shaped during his collegiate years in Pune. This formative period honed his ideology fervor, preparing him for the scholarship in England that would soon follow.

This journey, initiated under the gaze of Aṣṭabhuja Devī, was not just a pursuit of academic excellence but a mission imbued with a deep-seated commitment to India’s liberation

This narrative is a tribute to that journey—a narrative that captures the essence of a man whose life was a relentless pursuit of freedom, not just for himself, but for his entire nation.

Savarkar stepped onto the streets of London in 1906 with a sense of anticipation and resolve. The city, with its grandeur and historic significance, stood in stark contrast to his homeland. Yet, amidst the unfamiliarity, he saw an opportunity—a chance to garner support for India’s independence and to challenge the very heart of British imperialism.

To fully appreciate the depth of Savarkar’s resolve and the complexity of his strategies, we would also be delving into his autobiographical narrative about his times in London titled, ‘Inside The Enemy Camp.’

This insightful work not only chronicles Savarkar’s experiences but also highlights the significant figures who influenced his ideological and practical development during his time in England—one of the most notable among them being Shyamji Krishna Verma.

Summarizing his life journey: during his early years Shyamji Krishna Verma was potentially orphaned from a very tender age, born on October 4, 1857, in the sleepy little town of Mandavi in Gujarat. Notwithstanding the apparent adversities of his early life, his relatives fortified in him the growing strength of his academic calibre, especially in Sanskrit, which set his course to Bombay for academic studies. Under the guidance of Svāmī Dayanand Saraswati of Arya Samaj, Shyamji’s intellect came of age. He started lecturing all over India and soon made a name for himself by the appreciation of scholars and top people.

His mastery of Saṃskṛta brought him to the notice of Professor Monier Williams of Oxford University, who advised his entrance to Balliol College in 1879. In Oxford, his studies merged Saṃskṛta, Greek, and Latin, and the fruits were an outstanding lecture delivered to the Royal Asiatic Society in 1881. On his return to India, he served with distinction in reputable administrative roles, such as the office of Diwan of Ratlam and Udaipur. However, he ultimately got disillusioned with the colonial administration as the British authorities were always at loggerheads with his later revolutionary activities.

The political arrests of leaders like Balgangadhar Tilak, however, in 1897, sped up his move back to England, where his political consciousness was awakened through the injustices of British rule and the writings of Herbert Spencer. In 1905, he founded ‘The Indian Sociologist’ where his radical views were professed in favour of direct action against British oppression.

His zeal for the freedom of India impelled him to establish the Indian Home Rule Society and India House in London in 1905.

These institutions proved to be breeding centers for revolutionary ideologies and activities in which young Indian nationalists were streamlined and equipped to oust British rulers.

It was in India House that Shyamji Krishna Verma met Vinayak Damodar Savarkar. Having recognized the potential of Savarkar, Shyamji offered him much more than just refuge and resources; he offered intellectual and moral support. Through his mentorship, Savarkar found his groove, publishing his magnum opus on the 1857 uprising. This significant incident occurred as Savarkar took a firm stand against a British play that mocked the martyrs of the 1857 uprising, on the event’s fiftieth anniversary.

This affront to the memory of the 1857 martyrs compelled Savarkar to respond powerfully. His efforts were aimed at correcting the distorted portrayal of India’s first war of independence, which many in the British public saw through a colonial lens. Savarkar’s response was not merely reactive but a calculated act of intellectual defiance. Later the book was published with the title ‘Indian War of Independence 1857’, and it was also published in Holland in 1908.

Before that in 1907, a much more significant achievement Savarkar had was incorporating and expressing the profound influence of Joseph Mazzini on our politics, especially through his study and dissemination to important people like Surendranath Banerjee and Lala Lajpat Rai; thereafter, the literary and intellectual yearning of Veer Savarkar in London culminated in his translating some works of Mazzini into Marathi.

Veer Savarkar and the Echoes of Mazzini in Indian Revolutionary Thought

While residing in the scholarly confines of India House in London, Veer Savarkar’s discovery of Joseph Mazzini’s writings marked a pivotal turn in his revolutionary ideology. Mazzini, an Italian philosopher known for his radical thoughts on nationalism and democracy, had left a lasting imprint on the fabric of Indian political movements, influencing an entire generation of Indian nationalists.

Decades before Savarkar’s time in London, Mazzini and his compatriot, Garibaldi, were actively involved in the European revolutions of 1848-49. Their struggles and subsequent exile echoed across continents, resonating with Indian leaders who were grappling with British colonial rule. The news of the 1857 Indian Rebellion, which highlighted figures like Tatya Tope and Rani Laxamibai, reached these Italian revolutionaries, sparking a profound empathy and a symbolic bond between the Indian and Italian struggles for independence.

In the aftermath of the 1857 rebellion, a period of relative political quietude in India was shattered by the orations of Surendranath Banerjee, who had been deeply moved by Mazzini’s life and ideologies. Banerjee’s speeches from 1875 to 1878 not only celebrated Mazzini’s revolutionary strategies but also sowed the seeds of what would become a burgeoning nationalist sentiment among the youth of Bengal.

Although Banerjee highlighted the fervour and spirit of nationalism by Mazzini he obscured the aspects of where the spirit of armed revolution was to be revealed. Inspired by Mazzini’s secret society, Young Italy, numerous non-revolutionary secret societies sprang up in Bengal, embodying Mazzini’s ideas of patriotism and resistance, albeit in a subdued form.

Further north in Punjab, Lala Lajpat Rai became another monumental figure in Indian politics to embrace Mazzini’s ideals. After attending a lecture by Banerjee, Rai was so inspired that he went on to study Mazzini’s works in detail and eventually wrote a biography in Urdu to disseminate Mazzini’s revolutionary ideas among the Indian youth.

Meanwhile, in Maharashtra, the spirit of revolution was already potent, with local heroes and events from the 1857 revolt serving as primary inspirations. However, the ideological impact of Mazzini began permeating through the writings of local intellectuals like S. M. Paranjape, who drew parallels between the Italian and Indian quests for freedom, and Mr Ghanekar, who penned the first biography of Mazzini in the region around 1900.

Savarkar’s translation of Mazzini’s works into Marathi was not merely an academic exercise, but a deliberate act to harness these stories of Italian resistance, and tailor them to ignite a similar fervour among Indians. His efforts culminated in a book that not only translated the Italian’s writings but also contextualized them to resonate with the Indian struggle, urging his compatriots to adopt a more active stance against British rule.

Savarkar’s translation work culminated in the publication of these volumes, a task fraught with challenges. He coordinated with his brother, Babarao, and other members of the Abhinav Bharat Society to manage the logistics of publication amid intense scrutiny by British authorities. Their efforts were met with success, as the translated works quickly sold out within the first three months, reflecting the eager anticipation and revolutionary enthusiasm among the Indian community.

Through his scholarly endeavours in London, Savarkar thus wove the Italian revolutionary’s ideas into the Indian nationalist narrative, demonstrating the global interconnectedness of the fight against oppression. This intellectual bridging crafted by Savarkar helped solidify the ideological groundwork for a more concerted Indian independence movement, reflecting the enduring influence of Mazzini’s principles on Indian soil.

Starting with the invocation “स्वतंत्र लक्ष्मी की जय” (Victory to the Goddess of Freedom), Veer Savarkar dedicated his book to his political idols, Lokamānya Tilak and Śrī Shivram Madhav Paranjape. This book rapidly gained popularity, which led the Government of British India to ban it. However, it was republished in 1946 in India, resurging to influence a new generation.

The previous work on the First War of Independence in 1857 faced a similar fate; it was banned even before it could be printed, owing to the profound impact Savarkar’s book on Mazzini had on the Indian psyche. In response, V.V.S Iyer, a Tamil admirer of Veer Savarkar, translated this significant work into English, allowing it to be published in Denmark, beyond the reach of British Indian authorities.

Such was the stature and influence of the books in the discourse of Indian nationalism that its next publication was carried out by Shaheed Bhagat Singh and Subhas Chandra Bose, calling it the ‘Bhagavad Gītā of Revolution’. Such was their rightful endorsement of the works that greatly helped in spreading and focusing the many revolutionary movements at the time all over India.

Veer Savarkar’s tenure in London showcased his multifaceted approach to advancing the Indian independence movement through strategic networking and profound political activism. Initially, he harnessed the potential of the London Indian Society, where a vibrant community of Indian students and intellectuals exchanged ideas and formulated strategies for independence. This platform fostered a robust sense of unity and purpose, serving as a crucible for ideological development.

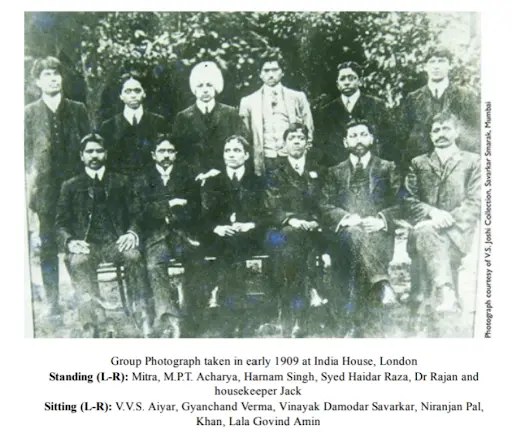

The India House in London witnessed overflowing Lecture Halls on weekly Sunday meetings. In these meetings, Savarkar delivered speeches on the history of Italy, France and America and the revolutionary struggle they had to undergo. A host of young people came under Savarkar’s influence during this period; prominent among them were Bhai Parmanand, Lala Hardayal, Virendranath Chattopadhyaya, V.V.S. Iyer, Revabhai Rana, Gyanchand Varma, Madame Cama, P.M. Bapat, M.P.T. Acharya, W.V. Phadke and Madanlal Dhingra2.

Further deepening his political engagements, Savarkar became actively involved in the East India Association. This forum was pivotal for voicing Indian grievances and advocating for reforms, thereby honing Savarkar’s diplomatic skills and expanding his network among both Indian and British sympathizers.

Savarkar’s strategic vision extended well beyond these initial platforms. Recognizing the potential of a synchronized global movement against British imperialism, he established contacts with revolutionary groups in Russia, Ireland, Egypt, and China. Savarkar envisioned a united anti-British front, aiming for a coordinated uprising across these nations to simultaneously challenge the British Empire. His articles on Indian affairs were not only published in ‘Gaelic America’ of New York but were also translated into German, French, Italian, Russian, and Portuguese and disseminated globally to rally international support.

Additionally, Savarkar’s revolutionary activities included practical preparations such as procuring arms and disseminating bomb-making knowledge. He meticulously studied British law to protect Indian activists legally and effectively challenge British authority. His writings served as a powerful tool for mobilizing support, and he actively contributed to international forums, highlighting India’s plight. Notably, Madame Cama and Sardar Singh Rana were deputed by Savarkar to represent India at the International Socialist Congress in Stuttgart, Germany, in 1907, further amplifying his international advocacy efforts.

Savarkar also supported broader nationalist movements, exemplified by his endorsement of the establishment of a Jewish State in Palestine.3

His ability to win over Irish sympathizers within Scotland Yard, who assisted in smuggling political literature, underscored his adeptness at building strategic alliances, even within the ranks of his adversaries.

Through these activities, Savarkar not only energized the Indian diaspora but also laid a robust foundation for the broader phases of India’s freedom struggle, demonstrating a profound understanding of international dynamics and the importance of a cohesive and coordinated approach to dismantling colonial rule.

One could not go ahead in this narrative without mentioning two important personalities: Madan lal Dhingra and Pandurang Mahadev Bapat, who took up crucial actions during their years in London along with Veer Savarkar.

Madan Lal Dhingra

Born on February 18, 1883, in Amritsar, Punjab, into a prosperous family, Dhingra completed his early education in India before moving to England to study engineering at University College London. Initially leading a life marked by ease and epicurean pursuits, Dhingra underwent a profound transformation upon encountering Savarkar4. Under Savarkar’s influence, Dhingra developed a fiery revolutionary fervor. He embraced the belief that the liberation and independence of their motherland were paramount pursuits, beyond which nothing else mattered. This conviction ignited a fierce passion within Dhingra - on one occasion, when challenged to prove his commitment to the cause of Swarajya, Dhingra pierced his palm with a sharp, long needle - a stark display of his unyielding resolve5. Inspired by Savarkar’s writings and speeches, Dhingra came to see himself as a soldier in the war for Indian freedom.

One of the most defining moments in Dhingra’s life was the assassination of Sir William Hutt Curzon Wyllie. On July 1, 1909, during a public event in London, Dhingra took the radical step of shooting Wyllie, a senior British official, who was pinpointed thereafter to ignite a broader insurrection amongst Indians against their British oppressors. It was a bold and direct protest against British colonial rule, audaciously performed, much more than a mere personal vendetta.

The reverberations of Dhingra’s actions went much further than the immediate repercussions of the event. He was captured on the spot, hastily tried, and sentenced to death. He was executed on August 17, 1909. Dhingra’s supreme sacrifice dramatized the intense protest that was building up among Indians and how far they were willing to go in their struggle for Home Rule. His martyrdom became a grim, defiant symbol that acted as a fillip to the fledgling Indian independence movement.

Pandurang Mahadev Bapat

Widely known as Senapati Bapat, Pandurang Mahadev Bapat commenced his academic life in Pune amidst the rise of the Indian freedom movement. Taking up engineering sent him to England, where a visit with an intellectual giant among national freedom fighters called Vinayak Damodar Savarkar steered his life in a definitive direction. Bapat was under the influence of such prominent Indian nationalists as Vinayak Damodar Savarkar and naturally took up their revolutionary ideas. This immersion plunged him into full-fledged participation in the revolutionary movement, bomb-making, and dissemination of revolutionary propaganda. His fervent commitment even led him to contemplate dramatically destroying the Houses of Parliament.6

However, the external tempering of Bapat’s revolutionary zeal came from two sources. The immediate aftermath of the Alipore Bombing in 1908, and a subsequent period of hiding prompted introspection. A widespread unawareness of the masses, among whom he travelled extensively across India, regarding their being enslaved by the British, came as a life-changing experience to Bapat. His emphasis henceforth shifted from immediate overthrow to something strategic – that of educating and awakening. This shift in emphasis was due, to an extent, to Savarkar’s influence; and it drove home the point that the British had not only to be fought - but it also informed and mobilized people towards a national struggle for freedom.

Following the execution of Madan Lal Dhingra for the assassination of Curzon Wyllie, evidence increasingly pointed to one man who was rapidly becoming a significant threat to the entire British colonial regime in India: Vinayak Damodar Savarkar.

The British authorities were convinced that many revolutionary activities were directly or indirectly linked to him. Notably, Savarkar was involved in disseminating bomb-making techniques by secretly sending manuals to the Bengal Presidency. This had a profound impact, as demonstrated when Khudiram Bose used one of these manuals to learn how to make bombs for the attempt to assassinate Kingsford, a magistrate involved in the Muzaffarpur Conspiracy Case. Khudiram Bose, along with Prafulla Chaki, was subsequently executed, becoming one of the first Indian revolutionaries to face such a fate under British rule.

Another major incident linked to Savarkar was the arrest of his elder brother, Babarao Savarkar. Since targeting Savarkar directly under British laws proved challenging, the Government of India focused on Babarao instead. He was sentenced to the Andaman Islands and transported there on June 9, 1909. This action by the British prompted Anant Laxman Kanhere to assassinate Arthur Mason Tippetts Jackson, the District Magistrate instrumental in the arrest and prosecution of Babarao Savarkar, for printing a sixteen-page book containing the songs of Kavi Govind. Jackson’s assassination is considered one of the most crucial revolutionary turning points in Maharashtra, marking a significant escalation in the fight against British colonial rule.

As the British and the Indian Government intensified their efforts to curtail Vinayak Damodar Savarkar’s revolutionary activities, the nationalist leader faced increasing pressure. Amidst this turmoil, Savarkar received the distressing news of his brother’s arrest, along with reports of other members of Abhinav Bharat being detained and persecuted. During this period of darkness, the resilience of Veer Savarkar’s spirit was evident in a poignant letter he wrote to his sister-in-law, Yesu Vahini, the wife of Babarao Savarkar.

Deeply saddened by his brother’s imprisonment and the harsh penalties of Kala Pani, a sentence of life imprisonment in the Andaman Islands, notorious for the brutality and low survival rate) in addition to the arrest of his youngest brother, Narayanrao, on suspicion of criminal involvement, Savarkar offered words of solace and resilience. In his letter, he drew upon the imagery of fleeting life and eternal remembrance, saying:

अनेक फुले फुलती, फुलोनिया सुकून जाती त्यांची गणती माहिती कोणी ठेवली असे, ऐसे गजेंद्र सोंडे उचलून श्रीहरी चारिणी अरपोनि ते फुल मोक्षदायी.

Numerous flowers bloom, and many wither away; who keeps count of them? Yet, the one plucked by the trunk of Gajendra and offered to Shri Hari Vishnu will grant true liberation and will be forever remembered.

Through this metaphor, Savarkar conveyed a message of hope and purpose, implying that while many sacrifices may seem forgotten, those made in true devotion to a cause will achieve eternal significance and contribute to the ultimate liberation of their nation. His words sought to uplift and fortify his sister-in-law.

Such sacrificing nature and intellectual tenacity were rare traits, seldom observed among the leaders of that era. For Savarkar, the principles of svatantratā (independence), svadeśa (homeland), and svarājya (self-rule) were not only his goals but also the forces that fortified him during those arduous times. His resolve was fueled by an unyielding dedication to these ideals, driving him to endure with remarkable resilience.

This staunch spirit was not confined to Savarkar alone; it permeated through his entire family.

The women in the Savarkar household, too, exemplified extraordinary fortitude.

Their strength was born from a profound commitment and an intense sense of sacrifice toward the overarching goal of liberating their motherland.

The British government launched a meticulously orchestrated campaign, utilizing letters and telegrams to persuade the Benchers of Gray’s Inn to deny Vinayak Damodar Savarkar’s call to the Bar. Despite the lack of concrete evidence to support the charges laid by Gray’s Inn, Savarkar was still barred from practising law due to suspicions surrounding his activities. This incident was later leveraged by the British authorities to justify issuing a warrant against him.

In the wake of Curzon Wyllie’s assassination, Savarkar’s defiance shone brightly. At Caxton Hall, he stood unyielding, refusing to condemn Madan Lal Dhingra. He extended his protest by penning a letter to The Times, articulating his stance with clarity and conviction, and ensuring Dhingra’s silenced voice was heard through a statement he published in the Daily News on August 16, 1909.

The following November, as his health deteriorated, Savarkar sought refuge in Wales, hoping to recover. It was here, amidst the tranquility of Brighton, that he penned a Marathi book on the history of the Sikhs—a testament to his indomitable spirit. Yet, during this period of supposed respite, he was struck by personal tragedy—the death of his son, Prabhakar. But even this profound loss did not deter him.

By January 1910, with the threat of arrest looming, Savarkar moved to Paris. However, the British pursuit was relentless, and on February 8, 1910, he was targeted under the Fugitive Offenders Act of 1881 for a speech made years prior and an alleged crime in England. The evidence was tenuous at best, but the colonial machinery was grim on his capture.

In a display of leadership at audacious defiance, he came back to London on 13th March 1910 with a steely resolve to meet the empire that had denied him the very spirit he cherished. Vinayak Damodar Savarkar stood apart as a revolutionary, embodying the persona of a dhīrodātta (धीरोदात्त)—a term from ancient Indian lore that describes the self-controlled, exalted hero of great excellence.

His time in London showcased these attributes distinctly. Savarkar was neither boastful nor overtly assertive, yet his resolute nature and firm purpose resonated deeply. Each of his actions during this period demonstrated self-control, resolve, and quiet assertiveness, mirroring the qualities of an ideal nāyaka, or leader. Faced with the gravest of challenges, Savarkar responded with a disciplined demeanor and strategic poise, navigating each situation with the steadfastness of a seasoned warrior in the quest for India’s independence.

As we will reflect on the difficult period of his incarceration in our next article, let the last thought of this narration be that of the poet within Veervar Savarkar emerging vividly, revealing his innermost thoughts and feelings. While on Brighton Beach, during a moment of profound introspection, he composed one of his greatest masterpieces. However, this creation did not spring from a fountain of blissful creativity; rather, it was born from a tempest of raw emotion. Overwhelmed by the pain of his experiences, tears filled his eyes as he sang Saagara pran talamalala.

This poignant scene captures Savarkar not just as a revolutionary, but as a roaring poet, trembling with the intensity of the emotions that coursed through him during those trying times.

ने मजसी ने परत मातृभूमीला I सागरा, प्राण तळमळला

भूमातेच्या चरणतला तुज धूतांI मी नित्य पाहिला होता

मज वदलासी अन्य देशिं चल जाऊंI सृष्टिची विविधता पाहूं

तइंजननी-हृद् विरहशंकितहि झालेंI परि तुवां वचन तिज दिधलें

मार्गज्ञ स्वयें मीच पृष्ठिं वाहीन I त्वरित या परत आणीनO Ocean, take me back to my Motherland

My soul in so much torment be! ||Dhru.||

Lapping worshipfully at my mother’s feet

So always I saw you

Let us visit other Lands to see

The abounding nature said you.

Seeing my Mother’s heart full of qualms

A sacred oath you did give her,

Knowing the way home, ‘pon your back

My speedy return you promised her.

विश्वसलों या तव वचनींI मी

जगदनुभव-योगें बनुनी I मी

तव अधिक शक्त उध्दरणींI मी

येईन त्वरेंकथुन सोडिलें तिजला I

सागरा, प्राण तळमळलाFell for your promise did I!

That worldly-wise ‘n able be I

Her deliverance better serve do I

’Pon returning, so saying I left her.

O Ocean, my soul in so much torment be! ||1||

शुक पंजरिं वा हरिण शिरावा पाशींI ही फसगत झाली तैशी

भूविरह कसा सतत साहुं यापुढती I दशदिशा तमोमय होती

गुण-सुमनेंमीं वेचियलीं ह्या भावें कीं तिनें सुगंधा ध्यावें

जरि उध्दरणीं व्यय न तिच्या हो साचा हा व्यर्थ भार विद्येचाLike a parrot in a cage, like a deer in a trap—

Oh so duped am I

Parting from my mother forever—

Besieged by darkness am I!

Flowers of virtue gather did I

That blessed by their fragrance she be.

Bereft from service for her deliverance

My learning a futile burden it be,

ती आम्रवृक्षवत्सलता रे

नवकुसुमयुता त्या सुलता रे

तो बाल गुलाबहि आतां रे

फुलबाग मला हाय पारखा झाला सागरा, प्राण तळमळलाThe love of her mango trees, oh!

The beauty of her blossoming vines, oh!

Her tender budding rose, oh!

Oh forever lost is her garden to me,

O Ocean, my soul in so much torment be!

Read next part here.

References

- https://savarkar.org/en/pdfs/inside_the_enemy_camp.v001.pdf

- https://eparlib.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/56237/1/Swatantryaveer_VDSavarkar.English.pdf

- https://eparlib.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/56237/1/Swatantryaveer_VDSavarkar.English.pdf

- https://eparlib.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/56237/1/Swatantryaveer_VDSavarkar.English.pdf

- Samagra Savarkar Charitra Pravachanmala Gurudev Shankar Abhayankar.

- Professor Shivajirao Bhosale, Savarkar Jeevan Vakhayan.