share this article

आसिंधु सिंधु-पर्यन्ता यस्य भारत-भूमिका ।

पितृभूः पुण्यभूश्चैव स वै हिंदुरिति स्मृतः ।।

āsiṃdhu siṃdhu paryantā, yasya bhāratabhūmikā |

pitṛbhū: puṇyabhūścaiva sa vai hiṃduriti smṛta: ||

Everyone who regards and claims this Bharatbhumi from the Indus to the Seas as his Fatherland and Holyland is a Hindu.

Thus spoke the man who carried the Hindutva flag and cradled Hindu civilization’s political thought with all his intellectual might, these words belonged to one who manifested prophecy preserved by destiny in the womb of time.

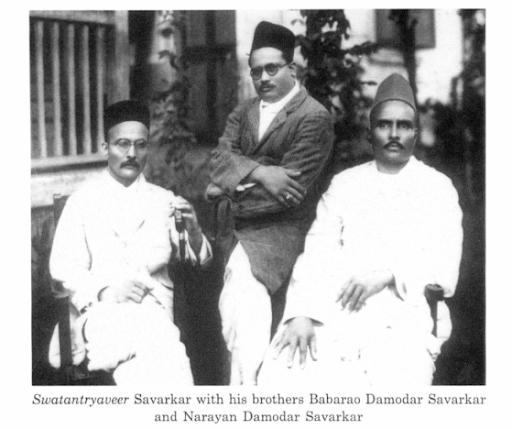

That man as we know him today was given the moniker ‘Svatantryaveer’ Writing an essay based on the caritra (biography) of such a nara-ratna is not a task one would deem easy. Nevertheless, one feels compelled to undertake this endeavor, feeling indebted as a Hindu to one of the few civilizational icons who illuminated the rise of Hindutva on the eternal mind slate of this Hindu civilization.

His works and struggles are as majestic as Vainateya, soaring through the highest of skies and delving into the deepest of seas. When we say we will deep dive into his caritra, what exactly is a caritra? When discussing great Vibhūtis (eminent personalities) like him, it is essential to understand what a caritra entails.

We, as common people, lead a life, but those who are reservoirs of profound moral values have a caritra. A caritra is a life story where the fire of nationalism burns fervently, or where the best of human potential is manifested through actions. An insatiable hunger for knowledge and its utilization for social cohesion and the building of a great society is caritra. Further, one’s will to sacrifice oneself in the yajña kuṇḍa (sacrificial fire) to build a great rāṣṭra is caritra.

Gajanan Digambar Madgulkar, known just by his initials in Maharashtra as Ga Di Mā (गदिमा), one of Marathi’s greatest poets and lyricists, says about Veer Savarkar:

चिरंजीव या हुतात्म्यांचे विजयी अभिमान, इतिहासाविन कोणी करावा ह्याचा सन्मान

Which means “Immortal or martyred, their triumphant pride, Without history, who can honor this tide.” In this verse, Ga Di Ma conveys that the glory of such a great revolutionary cannot be fully described by anyone; instead, it is history itself that will honor him.

Vishnu Vaman Shirwadkar, popularly known by his pen name Kusumagraj, drew his inspiration from Tilbhandeshwar Lane where the Mitra Mela1 was founded, where he describes, “This is the dark lane where the burning star of revolution was born.” Kusumagraj’s words reflect the profound impact of Savarkar’s revolutionary spirit, signifying the place of this revolutionary organization as a beacon of inspiration and a cradle of transformative action.

A multifaceted personality, Svatantryaveer Savarkar was a revolutionary, writer, historian, poet, and philosopher all rolled into one. He was also a mighty orator, capable of captivating thousands with his enthralling speeches. Savarkar pioneered the philosophy that can now be encapsulated as civilizational nationalism, where Hindutva became Rāṣṭrīyatva, and Rāṣṭrīyatva was akin to Hindutva.

His vision of Hindutva was not limited to religious identity but extended to cultural and civilizational unity. For Savarkar, being Hindu was synonymous with being an integral part of the Indian nation, transcending religious boundaries and emphasizing a shared heritage and common values. This holistic approach aimed to foster a strong sense of national pride and unity among the diverse peoples of India.

Svatantryveer Savarkar exhibited extraordinary poetic talent during his imprisonment in the Andaman Islands. Despite the harsh conditions, he composed voluminous poems, scratched his poems and other works on the walls with thorns and nails, and committed more than 10,000 lines to memory. His prowess in poetry can be compared to the giant Rath of Prabhu Jagannath, a symbol of grandeur and spiritual significance. His language was mature, serene, and serious, celebrating the glory of his motherland and invoking a cerebral elation in those who read or heard his verses. One of his famous poems is an ode to the Goddess of Freedom of Svatantrya Lakshmi. Titled as Jayostute (Victory to You) here are a few lines that inform us of his poetic prowess.

ज्योस्तु ते श्रीमहन्मंगले Iशिवास्पदे शुभदे

स्वतंत्रते भगवतिIत्वामहं यशोयुतां वंदे धृ

Victory to you, O Auspicious One,

O Holy Abode, Eternal Delight!

O Goddess of Freedom, Victorious One, we salute you!राष्ट्राचे चैतन्य मूर्त तूं नीतिसंपदांची

स्वतंत्रते भगवति I श्रीमती राज्ञी तू त्यांची

परवशतेच्या नभांत तूंची आकाशी होशी

स्वतंत्रते भगवती I चांदणी चमचम लखलखशी

Epitome of our National Soul, Goddess of Freedom O,

Of Virtue and Prosperity supreme Queen you are, lo!

O Goddess of Freedom, you are a star shining

In this darkness of slavery, alone in the sky gleaming!गालावरच्या कुसुमी किंवा कुसुमांच्या गाली

स्वतंत्रते भगवती I तूच जी विलसतसे लाली

तूं सूर्याचे तेज उदधिचे गांभीर्यहि तूंची

स्वतंत्रते भगवतीIअन्यथा ग्रहण नष्ट तेंची

O Goddess of Freedom, you are the blush that prospers,

On flowers as soft as cheeks, on cheeks as soft as flowers!

You are the depth of the ocean, the radiance of the sun,

O Goddess of Freedom, without you their worth is none!

Savarkar’s dedication to his cause was akin to camphor, which burns completely, leaving nothing behind

He burned with a single aim, one (saṃkalpa) resolution — to bring independence (svatantratā ) to his motherland. His unwavering commitment was to achieve swarajya (self-rule) and surajya (good governance) for the people of India.

While understanding the caritra of any revolution, we should focus on the converging point of understanding the social, political, economic, scientific, literary, artistic, educational, and religious situations. These eight facets, or aṣṭāṅga, shape the cultural and civilizational body of a nation. Tilak’s call for Swaraj (self-rule) and his emphasis on cultural revival and mass mobilization inspired Savarkar to pursue a path of active resistance against British colonial rule.

This realization was articulated by Swatantryaveer Savarkar in his writings. While Bhāratadeśa was ablaze with Anglo-Indian wars and major principalities were falling prey to the British Empire, the company rule was sustained until the jolt of 1857. Savarkar covers this in his seminal work on the First War of Independence titled Indian War of Independence, 1857, which is a landmark in Indian history. Not only did it raise forever the 1857 rebellion of the soldiers up from the ignominious distinction of being called the “Sepoy Mutiny,” it recognized all the forgotten heroes and their contribution to the freedom struggle. While the British were able to conquer the Maratha Empire, they were not able to conquer the Marathi people. This distinction underscored the resilience and indomitable spirit of the Marathi populace, who continued to resist colonial rule despite the fall of the Maratha empire in 1818.

In his book Indian War of Independence after extensive research, he distinctively presented the facts, highlighting the solidarity with which Hindus and Muslims united to confront their common adversary, the British. This narrative played a pivotal role in igniting patriotism among Indians, inspiring many to join the freedom struggle. The British, recognising the potential of this work to galvanize resistance, preemptively banned the book in India before its publication—a move virtually unprecedented at the time.

Inspired by Shivaji’s guerrilla tactics and strategic acumen, Savarkar sought to apply similar principles to the fight against the British

While understanding the character of the revolution, Savarkar understood the balasthāna (strengths) and ābālasthānas (weaknesses) of an armed revolution. This mīmāṁsa (analysis) of Bengali and Maharashtrian revolutionaries gave him a deep affection towards these regions.

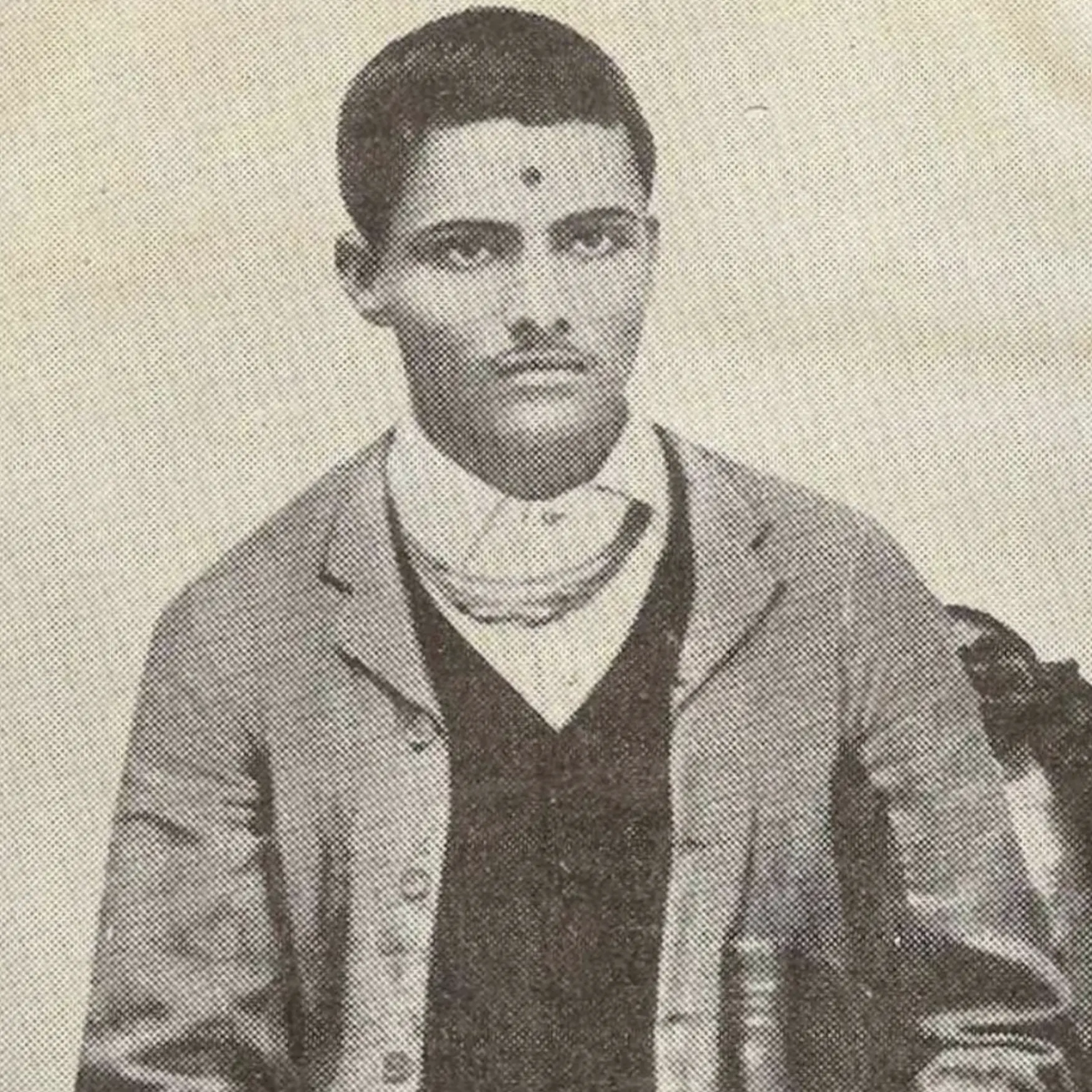

Svatantrayveer Savarkar was born in a Citpāvana Brāhmaṇa family, most of these Citpāvana Brāhmaṇas came from the Konkan region of Maharashtra and later migrated to various parts of Maharashtra. Employed by the Peshwas, this clan was known for its sharp wit and administrative acumen during the Maratha period.

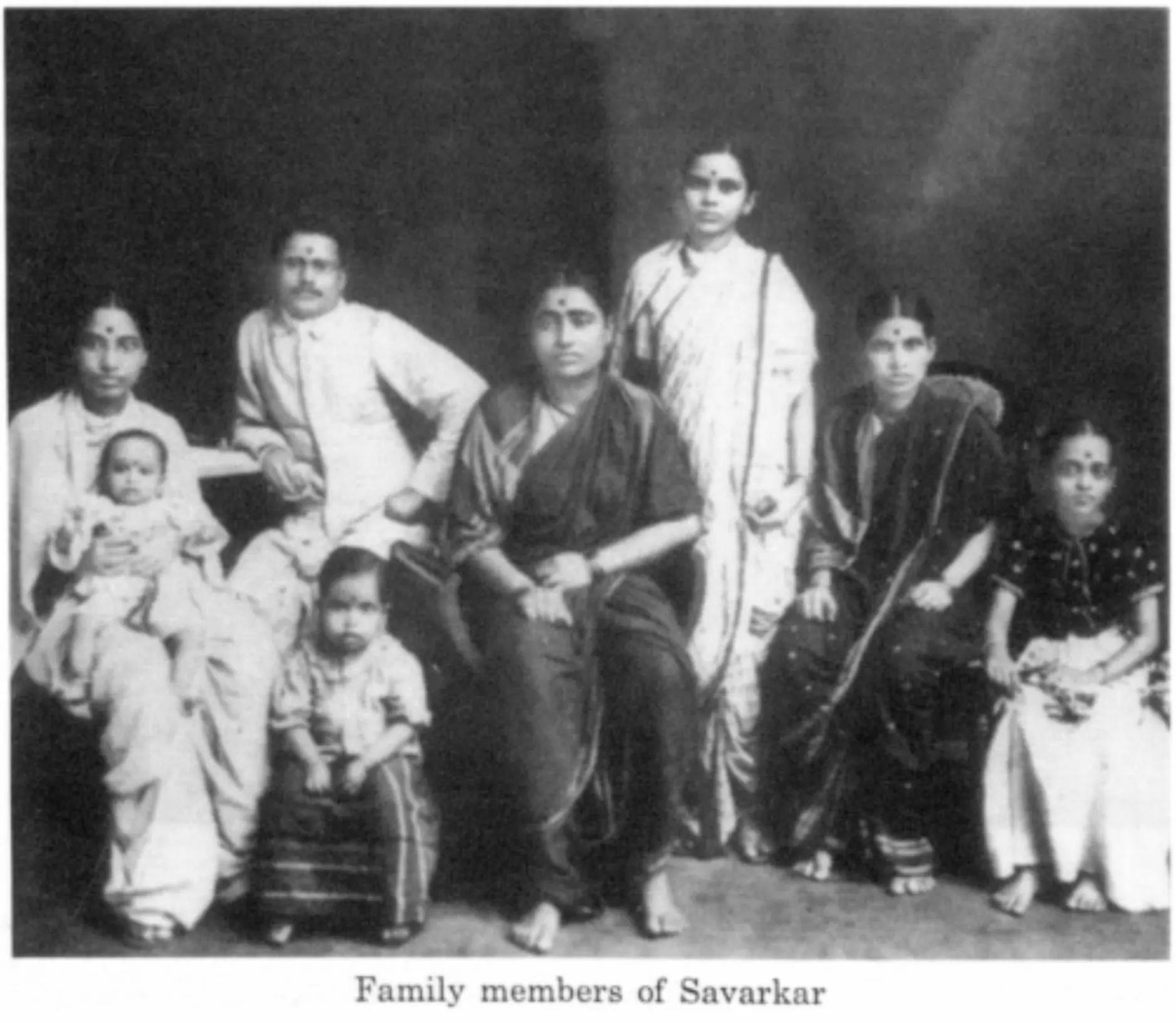

Having their roots near the areas of Guhagar and Chiplun, it can be assumed that the name Savarkar might have originated from a small hamlet named Savarwadi in this geography. Vinayak Damodar Savarkar was born on 28 May 1883, an auspicious day of Vaiśākha Śukla Ṣaṣṭhī, Śaka Saṁvat 1805, in Bhagur, a village near Nashik. His parents, Shri Damodarpant and Smt. Radhabai belonged to a prosperous middle-class family. The Savarkar family was blessed with four children: three sons, Ganesh, Vinayak, and Narayan, and a daughter, Mainabai.

All Savarkars were well-educated and had a deep and astute knowledge of the Vedas and Sanskrit. Vinayak grew up listening to passages read out by his father from the epics Mahābhārata and Rāmāyaṇa, as well as ballads and Bakhars on Maharana Pratap, Chhatrapati Shivaji, and the Peshwas. He was a voracious reader, devouring any book or newspaper from cover to cover, page to page. An inborn genius, Savarkar had a rare talent for poetry; his poems were published by well-known newspapers when he was hardly ten years old2. Young Vinayak, being an adventurous kid, loved playing with his younger brother and friends all around his village of Bhagur, Rahuri, and Trimbakeshwar.3

Misfortune fell on the family when he lost his mother Radhabai at the very young age of ten, as she succumbed to the plague. His father took on the role of both mother and father, caring for the family. Even as a young boy, Vinayak was very conscious of the sufferings of people. He was emotionally stirred by the miseries caused by famine and plague, compounded by the harsh treatment and excesses committed by the British Raj. Treating the peasantry of Kunbis who worked for his family as his own, he showed early signs of breaking the social stigmas that afflicted society.

After completing his primary education in Bhagur, he was sent to Nashik by his elder brother Babarao, who made immense efforts to educate his younger brother. In Nashik, Vinayak received an education in English and was exposed to colonial education, which further shaped his revolutionary ideas and commitment to India’s independence.

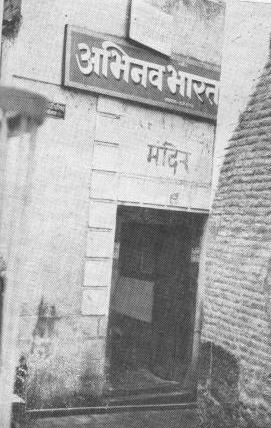

In Nashik, Vinayak met friends who would later become instrumental in the formation of Mitra Mela on 1 January 1900. This group included Vartak, Mashkar, Aba Pangle, Kavi Govind, and Vaman Datar, all of whom shared a common goal: the complete political independence of India. Mitra Mela was later renamed Abhinava Bhārata, closely resembling the ‘Young Italy’ movement of Giuseppe Mazzini and the revolutionary societies in Russia.

Tragically, Vinayak lost his father to the plague on 9 September 1898, which plunged the family into financial difficulties. Recognizing Vinayak’s brilliance, Bhaurao Chiplunkar, who later became Vinayak’s father-in-law, took on the responsibility of his education. He identified the spark in this brilliant mind and declared, “Vinayak is a son to me; I shall take on the responsibility for educating him.”4

In 1901, Savarkar married Yamunabai, Bhaurao’s daughter. The couple had three children—two daughters and one son. This support and personal stability allowed Savarkar to continue his education and further his revolutionary activities.

Completing his matriculation, Savarkar furthered his education in Pune, a hub of intellectual and revolutionary activities. Pune was home to great leaders and intellectuals such as Lokmanya Tilak, R.G. Bhandarkar, and Rajwade. Tilak, who later became Savarkar’s political and spiritual guru, had inspired him from a young age. Svatantryaveer was also deeply influenced by the political writings of Shivram Madhav Paranjape whose weekly called Kaal had a significant impact in shaping the political and ideological mind of young Vinayak.

Earlier, the assassination of two British Plague Commissioners by the Chapekar brothers in Pune on 22 June 1897, and the subsequent execution of Damodarpant Chapekar, deeply disturbed young Savarkar. He took a vow in front of Aṣṭabhuja Durgā to sacrifice his nearest and dearest, fighting fiercely unto his last breath, to fulfill the incomplete mission of the martyred Chapekar brothers. He vowed to drive the British out of his motherland and make her free and great once again. Greatness knows no age; just as Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj vowed to create Swarajya at a young age, so did Veer Savarkar’s vow to liberate his motherland chained in the foreign yoke. Savarkar took admission to Fergusson College, where the principal was Wrangler Paranjape.

An interesting anecdote is that the Superintendent of Police of Nashik, Montgomery, in his report on extremists in the district, noted that a fiery orator named Savarkar had left for Pune. Montgomery observed that such a young orator could articulate the most complex philosophies in simple yet engaging terms, speaking from a sharp, intellectually superior, factual, and historical perspective. He considered such young men potential threats to the British Empire.

During his college years, Savarkar was deeply involved in revolutionary activities and impressed those around him. He spent his time spreading the word against the British Empire. His eloquence had a profound impact on the young minds around him, inspiring them to join the struggle for independence.

Hundreds of young men joined the organization, and Vihāri, a Marathi weekly, became its mouthpiece, with significant contributions from Savarkar5. He urged his countrymen to reject everything English and to abstain from purchasing foreign goods. Inspired by his call to action, many students daringly organized bonfires of foreign clothes, with the largest one, supported and inspired by Lokmanya Tilak, occurring in Pune in November 1905. Consequently, disciplinary action was taken against young Vinayak by Wrangler Paranjape, who imposed a fine of ten rupees. This fine was easily collected by Savarkar’s friends, demonstrating their solidarity and support.

During this period, Mahatma Gandhi, then in South Africa, condemned the act of burning clothes—a stance he would paradoxically adopt fifteen years later

This irony often escapes contemporary discourse. Upon completing his Bachelor of Arts in 1905, Vinayak Savarkar, already a prominent figure in Pune’s revolutionary circles, decided to pursue higher education in London. With endorsements from Lokmanya Tilak and Shivrampant Mahadev Paranjpe, Savarkar applied for the famous Shivaji scholarship for advanced studies in England, departing in 1906. In a letter to Shyamji Krishna Verma, Tilak wrote:

This young man Savarkar is significant, and I recommend him for two reasons: firstly, his soul is imbued with an unwavering love for his motherland, and secondly, he possesses an impeccable character.

Savarkar also made a solemn declaration that he would dedicate himself solely to India’s independence and serve the nation with unwavering commitment. This declaration was subsequently sent to Shyamji Krishna Verma in London.

Going further, we shall delve into the events that unfolded during what Savarkar famously referred to as his time in London as śatrūcyā śibirāta शत्रूच्या शिबिरात, or “Inside the Enemy’s Camp.” in the next part of this series.

Endnotes

- Revolutionary group of Savarkar’s young friends whose principal aim was to attain complete political independence of India.

- Svatantryaveer Vinayak Damodar Savarkar

- Where his sister Mainatai (Mai) Bhaskar Kale lived.

- Samagra Savarkar Charitra Pravachanmala Gurudev Shankar Abhayankar

- Svatantryaveer Vinayak Damodar Savarkar