# Bodhas

World Civilizations - Mesopotamia, Part 3 | A Creation Story and the Epic of Gilgamesh

8 June, 2024

5908 words

share this article

In Part 1 of this series on world civilizations, we explored the political history, language situation, writing system and the lexicographic tradition of the Mesopotamian civilization. In Part 2 of this series, we explored the gods and temples of Mesopotamia.

Here in Part 3 of this series, we examine its creation stories, epics, heroes and philosophy.

Creation & Cosmogony: The Enuma Elish and the Bible

As we saw previously, in Mesopotamia water from the rivers and from the rains were not only the lifeline of agriculture and life; but also sources of disasters through floods and storms. In fact, the Mesopotamians thought of the world they lived in as a gap between two waters: First, there was definitely water below the ground which came up in springs, wells, and flowed in rivers. Then, there was definitely water in the sky, as the sky looked blue (hence full of water) and the water from the sky came down as rain. They had no knowledge of evaporation and scattering of light that made the sky blue. The thought was that there must definitely be a reservoir of water above the sky as there is one below in the ground. So in their cosmology, the world was inhabited between two layers of water. The earth was a narrow inhabitable place between two large reservoirs of water. So, a natural question to ask would be is:

Who first separated the waters below from the waters above?

This was the central focus of the creation stories in the ancient Near East. In many cultures, the primeval state of the universe is said to be watery chaos or a watery abyss. Taming these primeval waters is an important process in creation. There are lots of creation stories in Mesopotamia and they significantly varied from city to city as well, but the creation story in the city of Babylon eventually became well known due to the political dominance of the Babylonian Empire. This creation story is found in the text known as the Enuma Elish, and was sung every year during the festival of Akitu, the new year of Babylon to honor the patron god of the city - Marduk. We shall focus on this story in this article by taking it as a representative to get a peek into the creation stories of this civilization. So what does this creation story say?

It starts with the beginning of time when there were two primordial gods - Apsu, the god of fresh water and Tiamat, the goddess of salt water. Note that these primordial gods and the waters are pre-existent - hence the creation is not ex nihilo (out of nothing). The god Apsu and the goddess Tiamat mate together to produce many other deities which include the god of sand and silt. 1The text begins as:

When on high the heaven had not been named,

Firm ground below had not been called by name,

Nothing but primordial Apsu, their begetter,

(And) Mummu*–(Tiamat), she who bore them all, Their waters commingling as a single body;

No reed hut had been matted, no marsh land had appeared,

When no gods whatever had been brought into being,

Uncalled by name, their destinies undetermined—

Then it was that the gods were formed within them.

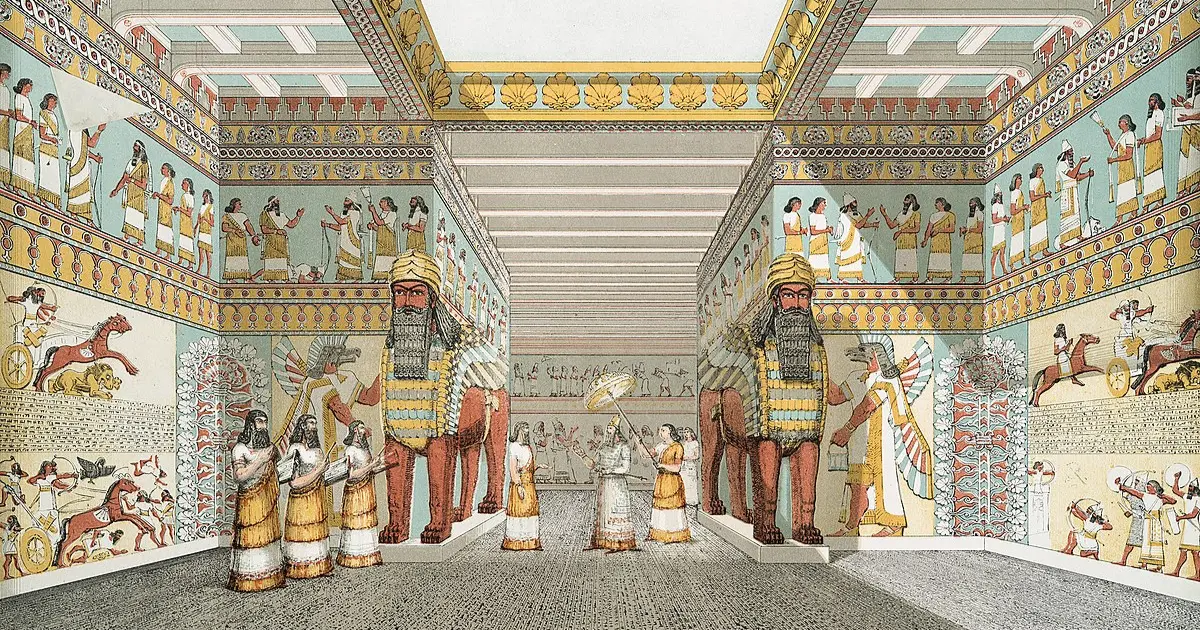

Another important god produced in this first generation is Anu (the sky god) who then mates with another goddess to produce Ea, the god of wisdom who is in the second generation. Then, these younger gods start making noise that upsets the first god Apsu. Apsu proposes to his wife Tiamat to kill all their children and grandchildren, to which Tiamat disagrees. Somehow, this plan leaks out among the younger gods. Ea plans and, by working with other gods, has Apsu killed. After which, Ea fathers another fourth generation god Marduk. Tiamat is furious when she comes to know that her husband Apsu was killed. She chooses one of her sons Qingu as her new consort and gives birth to a variety of monsters to kill the gods. Marduk eventually takes charge and there is a conflict between the younger gods headed by Marduk and the monsters headed by Tiamat and Qingu. Thus, there is a conflict between the primordial goddess and the later generations of gods (we will see this theme recurring in Greek mythology, too). Marduk, the wind god, blows and inflates Tiamat, bursts her body, killing her and then he splits her body into two - one part is put into the heavens and the other into the earth. Thus, the two halves of the body of the dead water goddess Tiamat are the waters below (ground) and the waters above (sky) respectively. The tears of Tiamat from her two eyes become the Tigris and the Euphrates river, her eyes become the sun and the moon - basically various components of the earth arise from her body. This story also explains why Marduk is the supreme god in the Babyonian pantheon, as he is the leader in this primordial war. This story of the universe created out of the various parts of a god or a goddess should not look strange at all, because it occurs in some form or the other in many cultures. In the Vedas which have many creation stories, one story tells us of the self sacrifice of the primordial deity Puruṣa, giving rise to the four varṇas of mankind.

Marduk tries to become the king of the gods, but the other gods do not want to worship, honor, and serve him. Hence, Marduk creates humanity from the blood of one of the gods Qingu (who had sided with the defeated Tiamat) to serve the gods and relieve them of cultic labor to him. After that, Marduk becomes the king of the gods by assigning the cultic duties to humans. He then makes Babylon as the center of the world and resides in it. The account ends with fifty eulogical names of Marduk.

This indeed does create a little pessimistic picture of humanity - humans are basically workers to the gods and were created as cheap labor for the divinities. Humans are an afterthought in creation, to just serve the gods, and they are not special in creation. Also this can explain why the gods are not particularly benevolent to humans - because humans came from the blood of Qingu, the god who rebelled against the gods. So, humanity carries that guilt from Qingu. This reflected the precarious lives that the Mesopotamians had to endure on a daily basis due to the cruel geography. There are other creation stories in Mesopotamia but they all agree that humans are essentially created to relieve the gods of their labors. This story and the worldview implied in it directly influenced the biblical creation story in Genesis2. Let us look at the beginning of the Bible where creation happens.

In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. Now the earth was formless and empty, darkness was over the surface of the Deep, and the Spirit of God was hovering over the waters.

Genesis 1:1-2

Note that even in the Bible, creation is not ex nihilo. There is primordial water as seen in the end of the second verse (hovering over the waters). The word that is translated as “Deep” in the Bible is actually “Təhom” in the original Hebrew which sounds like “Tiamat”. Now, remember that Hebrew is a Semitic language and related to Akkadian. Many scholars agree that the Hebrew word “Təhom” is etymologically related and is cognate to the Akkadian word “Tiamat”, the name of the goddess of the salt water. Even if we reject that hypothesis, we have another piece of direct evidence. In English, we do not use definite articles for proper names even if they refer to specific entities (for example: we do not say “The Ramaseshan is here” even though the name Ramaseshan refers to a specific person). But for proper nouns referring to specific things that are not names of people, we use proper nouns (eg. “a box” vs “the box” for a more specific box). Here, in the Hebrew Bible, the deep is a specific deep water associated with creation but the Biblical Hebrew text refuses to put a definite article “the” in front of the word “Təhom” anywhere in the entire text even when it refers to the specific primordial deep waters! This only can mean that the Biblical authors treated the word Təhom as a proper name and this directly spells Babylonian influence, since the primordial deep waters is nothing but the goddess Tiamat herself.

Next, consider the phrase in the verse that is translated as “spirit of God” which in the original Hebrew is “ruaḥ Elohim”. The word “ruaḥ” in Hebrew actually means “wind”. It is Christians who translate it as “spirit” because they want to bring in the Holy Spirit and justify the Trinity. Jewish translations render the phrase “ruaḥ Elohim” as “wind from God” in the English translation. So, we see that God’s wind is hovering over the surface of the deep waters. This should remind you of the Babylonian wind god Marduk who will blow up and kill Tiamat, splitting her body into two to create the waters below and the waters above (sky). This is what happens in the Bible too. Let us read a little further in the text.

And God said, “Let there be a vault between the waters to separate water from water.” So God made the vault and separated the water under the vault from the water above it. And it was so. God called the vault “sky.”

Genesis 1:6-8

Instead of the wind god splitting the deep waters into two, the God of the Bible does it in Genesis by sending the wind himself. The tower of Babel and the creation story are just two accounts to illustrate the influence of Babylonian culture on Israelite culture; and this is a vast area as there are so many analogies and parallelisms like these.

Note however, that there are other creation accounts from other cities as well, and from other texts. Another prominent creation account is from another text called Atra-Hasis, which is Akkadian but has its origins all the way to Sumer. It has a little different creation story to tell. These multiple creation accounts from various cities did not have any problems existing in the minds of individuals of the same civilization, and none of them fought out for their correctness. So, the Enuma Elish is just one of the many creation accounts (as we have lots of creation stories in Hinduism itself) - it was not the only account even in terms of popularity. It never played the role that the Genesis creation account played in the Judeo-Christian tradition - an account that was held as orthodox and the only one that was right or the only one that had to be believed.

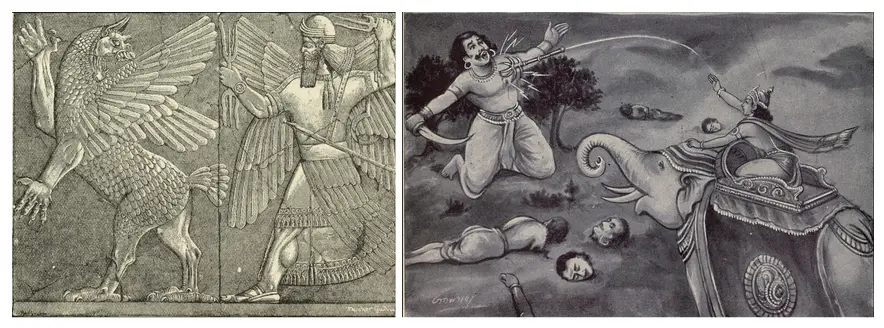

The motif of a sky or wind god slaying a primordial water god is found in Indian culture also. Consider the Rig Vedic tale of Indra slaying the demon Vṛtra(also known as Ahi, the snake) to recover all the waters of the earth that he had hidden in his belly. An epithet of Indra is Apsujit in Sanskrit, which means the one who won over the waters (Ap means water in Sanskrit - sounds like Apsuin Akkadian!). Also, does the Akkadian wind god’s name Marduk, sound like Marut, the Sanskrit term and god for wind?! This is probably a coincidence as Akkadian and Sanskrit are in distinct language families, and hence they cannot be etymologically related through common descent linguistically. But still the question of a sky or wind god slaying a primordial god to retrieve or tame the primordial waters will be a recurrent theme in many other cultures as well. It is as though the primeval state of the cosmos is assumed to be watery chaos in at least one creation myth of many cultures. But somehow in India, fancy leftist scholars tell us that Indraslaying Vṛtrarepresents immigrant Aryans conflicting with the indigenous Dravidians - why do they not try this toolkit to these dead cultures as well? They wouldn’t, because their real and underlying aim is balkanization, not academic knowledge.

The Culture Hero & Epic: Gilgamesh

The epic of Gilgamesh forms the core of Mesopotamian civilization in the same way the Rāmāayaṇa and the Mahābhārata do for our civilization. While not all would have been literate philosophers in ancient Mesopotamia who could think and do abstract philosophy, everyone in that civilization would certainly have been familiar with this epic. In this section, I will summarize the contents of the epic. Tablets of this epic have been found in not just Mesopotamia but also in far off places such as Turkey.

Almost all ancient civilizations had what we call “culture heroes”. The word hero originates from a Greek word that etymologically means “larger than life” - i.e., he does things which most or all humans cannot do. Most often, he serves as a model to emulate in some aspects. A hero always pushes the horizon forward, in terms of what we think of as being human. A culture hero also gives a sense of pride to his civilization, along with a sense of identity. The extraordinary powers of heroes are accounted for by various ways in various cultures - a hero can be powerful because he is :

- a god (e.g. Prometheus in Greek myth)

- an incarnation of a god (e.g. Rāma and Kṛṣṇa in Hinduism)

- a demi-god or part-god (e.g. Heracles/Hercules in Greco/Roman civilization)

- an extraordinarily powerful and strong human who, because of his deeds, is exalted to divinity after his death (e.g. Romulus, founder and first king of Rome who became a god)

Modern western culture has completely taken away the sacredness of heroes (e.g. Superman / Spiderman are not divine in any sense) in the same way it has taken away the gods from material nature or separated the religious from the secular - all of these separations go hand and glove with each other. But, they still have retained the other traits of heroes, as in Superman or Spiderman do indeed have superhuman powers.

Heroes also typically play an important role in the culture they are a part of. They can arrange or rearrange the world order, can help with creation or maintenance of order of the cosmos (e.g. avatars of Vishnu in Hinduism), can give a new skill and technique to the people of his civilization, can demonstrate how society should be arranged, and demonstrate or bring a body of laws,ceremonies, or ideals to aspire for (e.g. Rāma Rājya in Hinduism). They can also establish dynasties, thus enabling later historical kings to trace their descent from a hero’s dynasty (think of such examples yourself!). Let us now study the most important cultural hero of the Mesopotamian civilization - Gilgamesh. The tales of his adventures have been found in many tablets. Parts of it have survived in the original Sumerian, but complete versions have been found only in the Akkadian language. There was no single official canonized version of his story, and each tablet modifies the story in a slightly different way - but the overall story is consistent, and that is where we will focus.

The story opens with Gilgamesh, the king of the city of Uruk around 2700 BCE. The story is definitely based on an actual historical king of Uruk, but later got mythologized with time. At about 1800 BCE, we see complete versions of the renditions of the story of Gilgamesh. Gilgamesh is said to be the son of a human father and goddess mother, and is described as 2/3rd divine and 1/3rd human at birth!

He is a powerful king in Uruk when the story opens up. Gilgamesh rules as a dictator with an iron fist in Uruk, with no real care for his subjects. He exploits his citizens however he sees fit. As an extreme example, he deflowers all virgin women in his kingdom before they get married to their fiances! He uses the labor of the people for his extravagant building projects. The citizens are miserable and they cry out to the gods for help, who then create a man named Enkidu as a rival to Gilgamesh. Enkidu is born in the wild and lives as a wild man outside of civilization. He grows up among animals (like Tarzan). Some trappers discover Enkidu in the forest and then consult Shamhat, a temple priestess. She goes out and tames Enkidu. Shamhat has intercourse with Enkidu continuously for six days and seven nights and at the end of this process, Enkidu comes out as a new person! The animals now reject Enkidu as they feel he is not one of them anymore. So, when he goes back to Shamhat, she asks him to come to the city of Uruk and lead a civilized life. He is taught to eat human food, cut his hair, maintain his body, to cook food, and also hunt the animals that he once lived among.

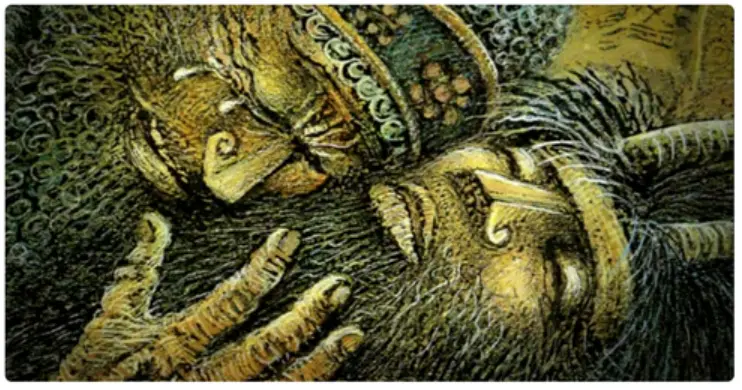

Gilgamesh in the meantime has a dream that he is going to get a companion friend with whom he will spend a lot of time. Enkidu shows up in Uruk and decides to save the oppressed humanity from the tyrant king Gilgamesh. Enkidu arrives in Uruk to challenge Gilgamesh, and they face off and fight each other in mortal combat. Gilgamesh almost wins, but Enkidu puts up a good fight even though he finally loses at the end and declares that he will never be able to defeat the half-god Gilgamesh. But at this point, the story twists. Gilgamesh admires the bravery and strength of Enkidu, and they now become best friends. They go out on adventures together to fight exotic monsters. Gilgamesh realizes that Enkidu is the long lost companion that he has dreamt of. Such male friendship (bromance) is a common theme in the epics of all cultures (some famous examples: Duryodhana & Karna in the Mahābhārata, Kṛṣṇa & Kucela in the Mahābhārata, David & Jonathan in the Bible, Achilles & Patroclus in the Iliad). Gilgamesh, now being distracted by his adventures with Enkidu, leaves his citizens unmolested who are relieved.

The epic could have ended here and would have itself served as a hero adventure. But this is just two-thirds of the story. Seeing this pair, the goddess of love, Ishtar, is attracted to Gilgamesh and proposes to him. But Gilgamesh rejects her. He has a fair reason to do so, because the fate of all the ex-husbands of Ishtar had never ended up pleasant. But Ishtar is furious and to have her revenge, Ishtar convinces the gods and has Enkidu die of a long illness. Gilgamesh tends to his friend all the days when he was ill. One of the moving points in the epic is the scene that describes the death of Enkidu, with Gilgamesh at his side who mourns intensely for his dead friend. Now, the story has another twist. Gilgamesh is forced to confront his own mortality and is terrified about it. If you have been alongside someone at the moment of their death, you will find the passages of that part of the epic so relatable and moving. We all know in an intellectual sense that we are going to die eventually and admit it as a fact in an abstract way; but actually witnessing it can change our psyche forever, and makes the knowledge of our mortality vivid and intense. This is what happened to Gilgamesh.

Gilgamesh now goes out on a quest to search for immortality. He wanders in lots of places as a traveling pilgrim. He meets a tavern woman named Siduri (kind of like a bartender in the ancient Near East!) who advises him that immortality is futile, and that he should enjoy the life he has remaining. A memorable extract from the epic goes as:

She [Siduri] answered “Gilgamesh, where are you hurrying to? You will never find that life for which you are looking. When the gods created man, they allotted to him death, but life they retained in their own keeping. As for you, Gilgamesh, fill your belly with good things; day and night, night and day, dance and be merry, feast and rejoice. Let your clothes be fresh, bathe yourself in water, cherish the little child that holds your hand, and make your wife happy in your embrace; for this too is the lot of a man”.

But Gilgamesh said to Siduri, the young woman: “How can I be silent, how can I rest, when Enkidu whom I love is dust, and I too shall die and be laid in the earth”.

The epic of Gilgamesh was widely known not only in Mesopotamia, but also outside it like the Levant, Turkey and so on; and tablets of the epic have been found from those regions. This epic had a huge influence on later civilizations that evolved in those regions. One famous example is that of the flood story that turns up almost identically in the Bible (more about this in another article dedicated to just these flood stories). But just look at the above advice that the tavern woman Siduri gives to Gilgamesha again, and compare it to the following verses from the Hebrew Bible, from the book of Ecclesiastes given below:

Go, eat your food with gladness, and drink your wine with a joyful heart, for God has already approved what you do. Always be clothed in white, and always anoint your head with oil. Enjoy life with your wife, whom you love, all the days of this meaningless life that God has given you under the sun—all your meaningless days. For this is your lot in life and in your toilsome labor under the sun.

Ecclesiastes 9:7-8

When Gilgamesh won’t budge, she asks him to go to Utnapishtim and his family, the only immortal humans in the world, to consult him. Gilgamesh then decides to go to seek Utnapishtim who lives on the edge of his world. When he finally does get there after a lot of adventures, Utnapishtim tells him that the gods had granted him immortality because he survived a great flood that swept the world (flood myths abound in all mythologies - about it in another article!). But that was a one time offer, and no one else can achieve immortality. Gilgamesh is instead directed to go in search of a miraculous plant that restores youth, as a compensation. He does acquire it - but when he is bathing, a snake takes it and runs away (explains why a snake sheds its skin)!

An utterly dejected Gilgamesh comes back to his city Uruk after a failed quest. Finally when he sees the city walls of his city Uruk, it gradually dawns on him that while humans individually can’t attain immortality, they can attain a sort of collective immortality by staying in the memories of their civilization. The city walls were as strong as when he had left, but now the city no longer was an object of temptation for him. He became a good king, cared for his subjects, built magnificent structures in his city, and did things that made the citizens happy and prosperous, instead of being a tyrannical ruler as he was before. He realized that true satisfaction comes not from transitory sensual pleasures, but from companionship and wisdom and making others happy. He is now more aware of his own limitations. The epic ends with a praise to Gilgamesh as: “O Gilgamesh, Lord of Kullab, great is thy praise”. Thus, we witness the inner transformation and maturation of Gilgamesh from a tyrant, selfish ruler to a caring, generous king who eventually transforms inwardly, achieves profound wisdom, and comes to terms with his own mortality; and is hence deified and worshiped as a god in that civilization.

Having seen the story, even though we cannot say how exactly the epic was understood by its own people in its own time, I think it is a safe bet to say that the epic conveys deep messages about some themes which are:

- Civilization vs Wilderness: The wealth and grandeur of the city of Uruk is contrasted to the wilderness and primitivity of the forest. The conflict between Enkidu and Gilgamesh is a conflict between civilization and wilderness. But the eventual friendship between Gilgamesh and Enkidu also seems to convey that these two worlds are not hostile to each other and are actually interdependent - one cannot exist without the other. Also note the role of sex in civilizing a person, as with Shamhat civilizing Enkidu from the wild.

- Taming of the Human Spirit: Gilgamesh’s inner transformation tells us that human life is a constant inward struggle, as well as a struggle between our own untamed aspects and civilized aspects.

- Inner Transformation: The way Gilgamesh sees his city Uruk initially and at the end is drastically different. Initially, he sees it as an object of rule and exploitation but at the end, he sees it completely differently: as an enduring legacy for his role in the larger civilization. Gilgamesh realizes that true satisfaction can’t be found in the transitory, sensuous temptations of the city; but from an experience of friendship and companionship. However, this experience also brings an awareness of loss and one’s own mortality. He finally confronts it by accepting it and working for others.

- Meditation on Life: The story of Gilgamesh ultimately offers a meditation on life, loss, and death. In the beginning, Gilgamesh is completely selfish - he wreaks havoc on his subjects even for momentary pleasure. Then, he fights his rival Enkidu and they become friends. With the death of his friend, Gilgamesh begins to meditate on his own mortality and accepts it only at the end of the epic. In this way, the epic offers a deep reflection on life.

- Civilizational Immortality: He gazes at the city he had built and realizes that these monuments that he has built, plus the memories of good deeds that he had done for his people, will survive long after he has passed away and has been forgotten. He realizes that civilizational immortality is the best consolation that is possible against the inevitability of his death as an individual.

The Gilgamesh epic definitely influenced the authors of the Bible. The flood story that Utnapishtim narrates to Gilgamesh exactly parallels the biblical flood account of Noah in the book of Genesis, up to its minute details. Israel is not at all prone to flooding while Mesopotamia is, and hence it makes sense that the story was borrowed by the later Israelites from the Mesopotamians. Fragments of the epic of Gilgamesh have been found abundantly throughout the Levant where Israel is. There are multiple versions and translations of the epic here - if you want to read the full epic yourself, refer to this translation by Maureen G Kovacs.

The epic of Gilgamesh has influenced modern western culture, too, after it was discovered - one example includes the TV series Star Trek: The Next Generation which follows the adventures of a starship Enterprise that explores newer worlds and meets aliens. In the 102nd episode (Season 5, Episode 2) named Darmok, the Enterprise makes contact with a Tamarian ship in orbit around the planet El-Adrel. It turns out that the Tamarians were already previously contacted by the Federation, but they could not understand the Tamarian language, as it was full of allusions to their culture and mythology - to convey even basic thoughts and intuitions. Likewise, the Tamarians could not understand the earthly language that is mostly straightforward. The captain of the enterprise Picard meets the Tamarian captain Dathon. But due to mistaken communication and intentions , they end up fighting like Gilgamesh and Enkidu. Then, they understand each other and become friends to fight a common enemy beast together. But Dathon dies in this battle and as he is dying, Picard communicates and recounts for Dathon, the epic of Gilgamesh (an earth myth) which Dathon seems to understand as it alludes to myth. Captain Dathon dies as he hears Picard uttering these words from the epic of Gilgamesh: “He who was my companion through adventure and hardship, is gone forever”. After he dies, the Tamarians absorb the story of Gilgamesh into their own mythology through the story of Picard and Dathon. One sees how much this epic has influenced modern civilization and resonates with people, even if it has been thousands of years since it has been composed.

Yes, myth making in the modern West has not ceased in the current scientific and rational age - instead of placing stories in the distant past and far-away lands, we now place stories in far-away galaxies and in the distant future. Our knowledge of history, geography, and this solar system has grown a lot due to science; and hence we cannot afford to place them logically, consistently in the distant past and distant lands (without raising questions of historicity and plausibility). However, the spirit of myth-making cannot be suppressed, hence it lets out itself in imaginary worlds (like Harry Potter) or distant galaxies and in the distant future - as we remain ignorant of them.

I think Gilgamesh did achieve his goal of collective immortality: After all, it has been 4000 years since he lived and here we are - still talking about him! He is referenced in even our TV shows. I find it emotional whenever I read this epic - especially at the end.

Despite the immense destruction of the culture and civilization of Mesopotamia by the cross and the crescent, these tablets have luckily come down to us and have enabled epics like Gilgamesh to survive through people like us - even though the descendants of Gilgamesh’s own people in modern day Iraq have completely forgotten him now, and the only god they worship is an Arabian, desert god.

And this should enable us to feel lucky for our own civilization - we remember and cherish our heroes and gods on a daily basis, and actively try to honor and emulate them. Civilizational continuity is a very big thing, not at all to be taken for granted. The wheel of time has now come down to us; and it is now our responsibility to pass on this magnificent civilization of ours to the next generation, to enable the collective immortality of our gods, heroes and values. Civilizational immortality, too, is not to be taken for granted - it is perilous and we should always be vigilant. In the next article, we will wind up our discussion on ancient Mesopotamia by discussing some of the memorable events and characters in its history, its laws, and a genre of literature called the wisdom literature.

Proverbs

Who doesn’t like proverbs? They are compact and simple traditional sayings, based on everyday perceived experiences that convey an underlying deep truth. In the Indian tradition, they are called by several names in several languages - subhāṣita in Sanskrit and pazhamozhi in my mother tongue, Tamizh. The Bible also has a book of Proverbs. Every tradition has its own set of proverbs. The Mesopotamian culture had its own proverb tradition.

Proverbs were mostly found in the Sumerian language. In the Old Babylonian period, bilingual proverbs are attested as well in the later periods. Here, we will sample some interesting proverbs. For the complete collection of Sumerian proverbs, you may consult the site in the reference here. As with any culture, proverbs come in a great variety - some proverbs state bitter truths, some convey a message, some are just outright funny, and some are rhetorical. As you read some of these proverbs that I have sampled here, you will realize the collective humanity shared by all of us - how the same human nature is expressed in various culturally specific ways in different cultures.

Some Mesopotamian proverbs:

- Whether he ate it or not, the seed was good.

- You should not cut the throat of that which has already had its throat cut.

- You don’t speak of that which you have found. You talk only about what you have lost.

- Possessions are flying birds — they never find a place to settle.

- The lives of the poor do not survive their deaths.

- He is at ease, he is pleased, he makes a living, he offers a prayer.

- He who eats too much cannot sleep.

- A heart never created hatred; speech created hatred.

- Marrying is human. Having children is divine.

- “Though I still have bread left over, I will eat your bread!” Will this endear a man to the household of his friend?

- Fate is a raging storm blowing over the Land.

- The poor man must always look to his next meal.

- The poor man chews whatever he is given.

- If a scribe knows only a single line but his handwriting is good, he is indeed a scribe!

- What kind of a scribe is a scribe who does not know Sumerian?

- Each fox is even more of a fox than its mother.

- He has not yet caught the fox but he is already making a neck-stock for it.

- Tell a lie and then tell the truth: it will be considered a lie.

- For a donkey there is no stench. For a donkey there is no washing with soap.

- The fox, having urinated into the sea, said: “The whole of the sea is my urine!”

- What has been spoken in secret will be revealed in the women’s quarters.

- I will feed you even though you are an outcast. I will give you a drink even though you are an outcast. You are still my son, even if your god has turned against you.

- While you still have light, grind the flour.

- Flies enter an open mouth.

- “I will go today” is what a herdsman says; “I will go tomorrow is what a shepherd-boy says. “I will go” is “I will go”, and the time passes.

- He who entered Elam — his lips are sealed. He who has to live in Elam — his life is not good.

- When righteousness is cut off, injustice is increased.

- A man raising his hand in anger does not see clearly.

- A loving heart builds houses. A hating heart destroys houses.

- Your worthiness is the result of chance.

- Good is in the hands. Evil is also in the hands.

- He who has nothing cannot let go of anything.

In the next and final section, we shall conclude the discussion on Mesopotamian civilization by focusing on three important topics that have major implications of the Western worldview: philosophy, the notion of a covenant, and the relation between mankind and nature.

References:

- Diodorus II 29.2

- Clarke, Benjamin “Misery Loves Company: A Comparative Analysis of Theodicy Literature in Ancient Mesopotamia and Israel.” Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies 2, no. 1 (2010). https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/imwjournal/vol2/iss1/5

- William G Lambert, “Babylonian Wisdom Literature”, Oxford University Press 1963

- To view the BT text online, refer: https://etana.org/node/582

- https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Job+38

Footnotes:

- First eight lines of Enuma Elish: Pritchard, James B., ed. (1969). “Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament” (3rd ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-03503-2.1969, pp. 60–61

- https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Genesis+1&version=NIV

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Tiamat

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vritra#/media/File:Storyof_Vritra(cropped).jpg

- https://www.learner.org/series/invitation-to-world-literature/the-epic-of-gilgamesh/experts-view-enkidus-death/