share this article

This series of articles studies other ancient civilizations: their history, their achievements, their intellectual thought, their religions and their eventual takeover by either Christianity or Islam.

I believe that this has valuable insights to offer for modern Hindus as well. First, we are one of the few surviving ancient civilizations who still maintain our continuity with the very beginnings of our civilization. Most of the world is now dominated by the two Abrahamic faiths - Christianity or Islam - and hence their history suffers a break with their ancient roots. On the one hand, we have their pre-Christian or pre-Islamic history which is subsequently disrupted and destroyed by the introduction of the new faith of the cross or the crescent. This moment is seen as a triumph of the true God and a movement from the dark ages of heathendom/paganism/jahiliyya [Arabic: ignorance] to the light of God, either as revealed in flesh through the incarnation or as revealed in his eternal book from heaven.

But India does not suffer from any such dramatic discontinuity. By that I do not deny that Indian civilization was merely static and imitated its predecessors. There were of course tremendous changes in society, culture and and an immense proliferation of new ideas and modes of thinking that vehemently challenged each other. But, one finds that despite all these variations and chronological change, there is an underlying thread that permeates them all. We as a civilization, always evolved by building up on whatever our ancestors did.

Never ever at any stage, did we claim that all the knowledge that we have previously acquired is useless or wrong and that we have to destroy everything of the past and have to start over

Study of other civilizations can offer us two insights. First, it can tell us how other peoples thought of and conceptualized reality and what were the foundational aspects of other ancient civilizations. Second, by studying how they succumbed to Abrahamic religions, such study would give us immense insight into what enabled us to survive as a civilization, and also lessons as to what we should focus on if we are to continue surviving as a civilization in the future.

There are four places in the old world of Europe, Africa, and Asia where civilizations first arose roughly around the same time - 3000 BCE. These are called the four cradles of civilizations. They are:

- India (Indus Valley civilization)

- Mesopotamia (modern Iraq)

- Egypt

- China

Civilization spread from these places to everywhere else. Let us first start with Mesopotamia, taking a closer look at its geography, political and cultural history, written script, and religion. In further installments of this series, we shall explore other cradles of civilizations and their successors.

Geography is Destiny: A Civilization from Mud

Imagine yourself to be time traveling to 5500 years ago and are on a flight that is flying over what is today Iraq, between the rivers Tigris and the Euphrates. What would you see? The answer would be that all you would see is a big, bleak, barren expanse of mud, mud, and mud. It would be mud, mud - everywhere.

After seeing this1, you would never bet that soon, this bleak barren expanse of mud would become one of the four cradles of civilizations. But yes, that is what indeed happened! The civilization that emerged from this region is now called in scholarship as the Mesopotamian civilization.

Geography does hugely influence other aspects of a civilization - not only its material culture but even its political history, religion, metaphysics and philosophy. This will be a recurring theme in this series of articles. So, there are three important geographical features of Mesopotamia that will dictate its evolution as a civilization.

Flatness - Mesopotamia is mostly flat - it has the Zagros mountain ranges in the North, but they are not absolutely impenetrable either. This region does not have any natural highly impenetrable geographical barriers. So, what does this translate to?

It means that the political history of Mesopotamia must be unstable - since there are no natural barriers, anyone with sufficient power can easily keep conquering and establishing large empires

By the same logic, such empires can fall as easily as they rose. So one sees that the political history of Mesopotamia is basically a story of one city gaining power and conquering all others to establish an empire and soon collapsing due to another city rising. Since it has no natural barriers, one expects that multiple peoples can come in easily and participate and mix in the churning brew of civilization.

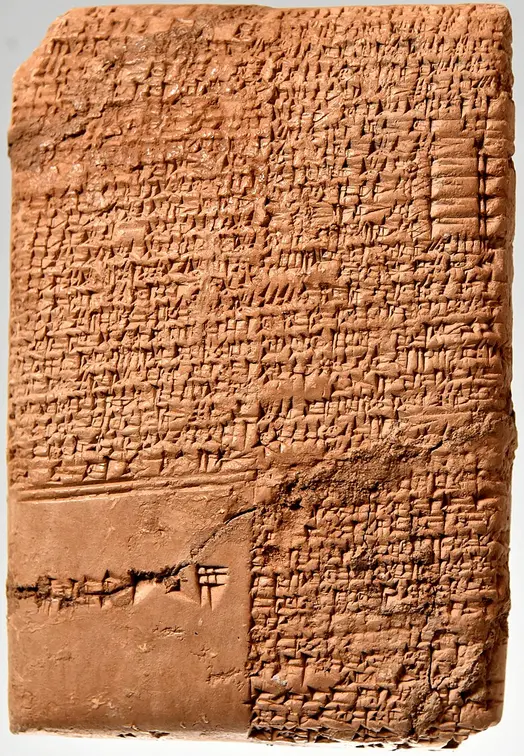

Floods - The most important geographical feature of the Tigris and the Euphrates rivers even today are flash floods. They flood very unpredictably into raging torrents, destroying everything in their path. Thunderstorms are also common in the region. And as though to add salt to the wound, the flooding occurred during harvest time, destroying all the crops that one had worked hard for. Thus, it looked like the floods were deliberately designed to give maximum destruction. This figure shows an extract from the Mesopotamian epic of Gilgamesh, regarding floods:

What does this translate to? One finds a subtle pessimism that pervades throughout this civilization. We find that the gods of Mesopotamia are highly mysterious, unpredictable and aloof from the people, just like the floods. Unlike in Egypt or India, we do not see any notions of eternal cycles in their worldview. This also explains why the Mesopotamians invested so much in the art of divination - predicting the future from present signs, by either looking at the sky or by inspecting the organs of sacrificed animals, and so on. This also motivated the Babylonian developments in astronomy for they saw in the movement of many heavenly bodies - a predictable order - which did not appear to be the case in the terrestrial everyday world.

Mud - In Mesopotamia, the only natural resource is mud - wood and stones are rare. Of course they did import commodities from other cultures. But their life line was mud and reeds that grew on marshes. Mud was used to make bricks and pottery. Mud was molded into clay tablets on which writing would be done. Reeds were used to make baskets, mats, boats, and fuel. The clay tablets, after being written upon, would be fired into bricks; and this is why Mesopotamian tablets are largely preserved intact and survived into modernity. This enables us to have a look at the literary works of this civilization.

A Brief History of Mesopotamian Civilization

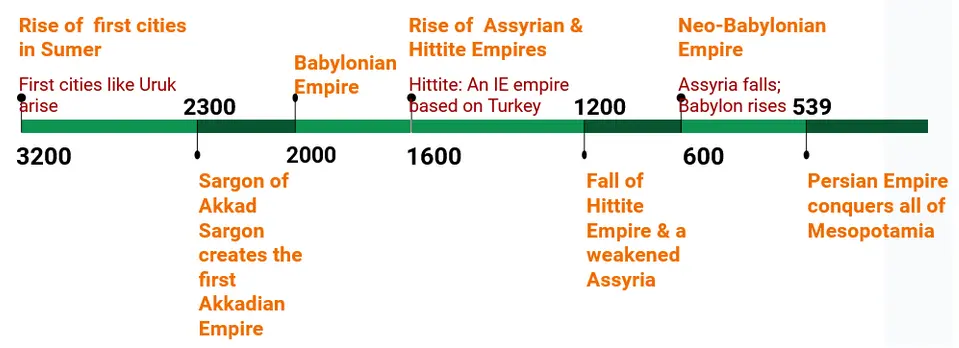

In this section, we shall sketch a brief overview of the political and cultural history of this civilization. Mere facts about events are not useful for most people; hence, only as much that is required to understand the intellectual aspects and worldviews of the civilization is presented. As was said in the geography section, Mesopotamia being flat with no natural impenetrable barriers, is predicted to see the rise and fall of many empires. This political history is summarized in this section.

Sumerian City-states

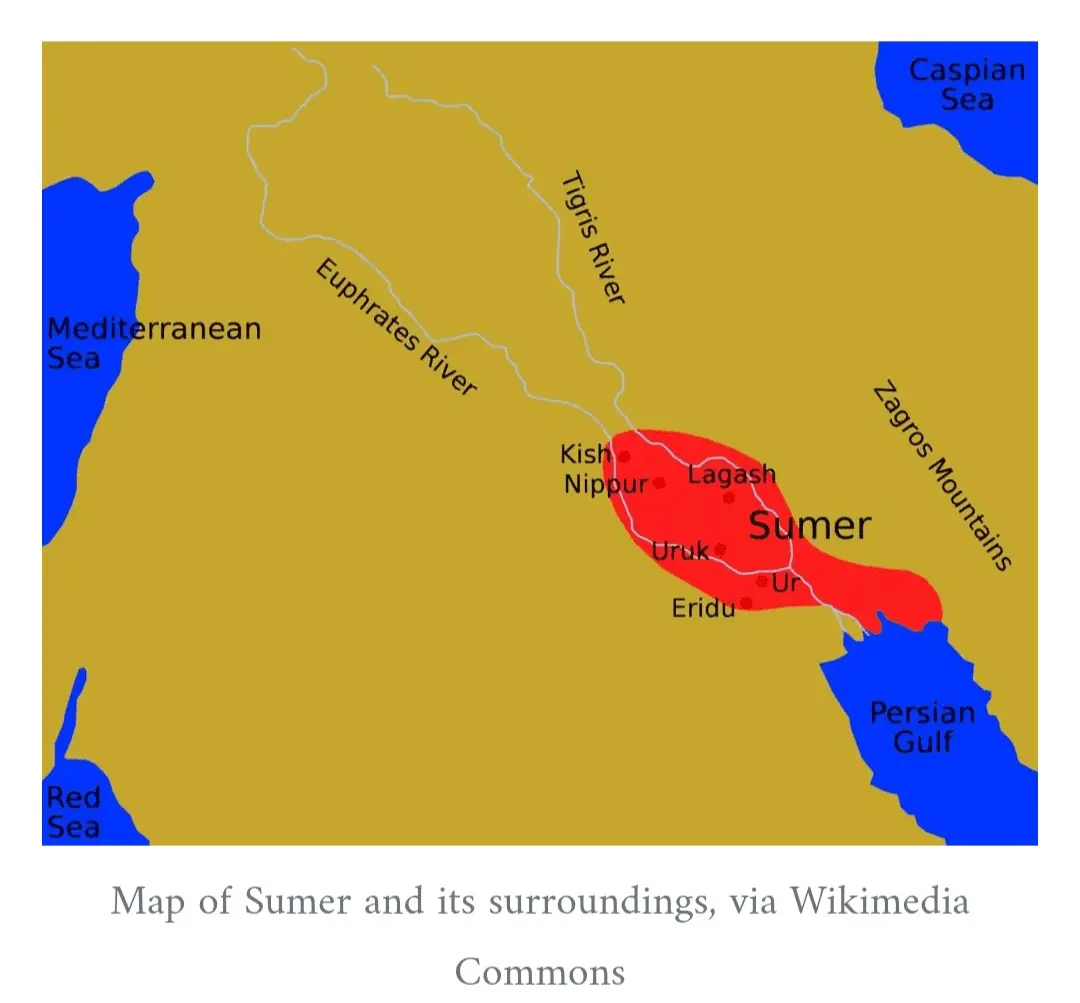

First, in the southern region of Mesopotamia called Sumer, there emerged various city-states starting from Uruk in 3500 BCE that began to possess high culture that are the signs of a civilization.

The language these city states spoke was Sumerian. Sumerian in linguistics is called a language isolate - which means that it is not related to any other languages that we know of, and hence is not a part of any language family. This Sumerian culture would serve as the nucleus for Mesopotamian civilization and as a center of attraction, like how the Vedic culture did for the Indian civilization. This would be the culture around which other groups would build and contribute to the pan Mesopotamian civilization. From here, civilization spread to other parts of the Middle East, and eventually trickled down further to even Syria and Turkey.

Sumerian city states developed a writing system for its language which is called the cuneiform script. We know that writing independently started in Sumer because we see the gradual stages in its development - first it starts off as pictograms - then it comes to encode words - then gradually to syllables which makes it a full blown script which happened around 2800 BCE. Initially, writing was used to keep accounts for trade but very soon, as the script developed, it began to be used for transmitting knowledge. Sumerian culture and hence gradually Mesopotamian culture would give immense importance to the written word for knowledge.

The Age of Empires: (2400 BCE onwards)

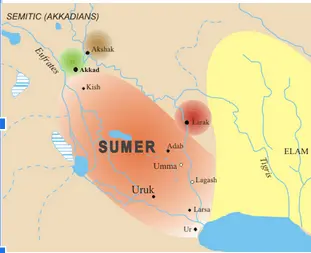

Next, we enter the phase of Mesopotamian history where a single city becomes powerful and conquers most of Mesopotamia to form a large empire. This is then followed by another city defeating it and forming another large empire around itself. Five important cities are notable in this process - Akkad, Ur, Uruk, Babylon, and Ashur.

The first to form a large empire was Sargon of Akkad from the north, who around 2300 BCE conquered all of Mesopotamia including the Sumerian city states to form the Akkadian Empire. But his empire lasted only for a few generations after which a brief period of political chaos ensued. Then, another empire called the Third Dynasty of Ur formed around the city state of Ur flourished for a few generations from 2100 to 2000 BCE.

After the third dynasty of Ur fragmented, the next city to rise to prominence was Babylon. The Babylonian Empire lasted from about 2000 to 1600 BCE. Also at this stage, one sees a massive influx of the northerners in Mesopotamia into the Southern Sumerian cities. The King Hammurabi (around 1800 BCE) who is famous for his law code fits into this Babylonian Empire.

The Elamites in Elam were a group of nomadic peoples who lived in the borders of Mesopotamia and were always threatening Mesopotamia in varying levels at multiple points in time. Their language Elamite has been attested in cuneiform - some consider it to be related to Dravidian but others see it as a language isolate.

After this period, in about 1500 BCE, another group of peoples called the Hittites, who were a culture based on modern Turkey, conquered some of the Mesopotamian city states and established the Hittite empire. At its peak, this empire controlled all of Turkey, parts of Mesopotamia and the Levant but here and there, rival kingdoms did emerge. One such famous kingdom is the Mittani Empire which spoke a form of Saṃskṛta and were Indo-Aryans. The Hittites adopted the institutions and culture of the previous Mesopotamian cultures and hence did not alter it that much. The Hittites thus hardly had any impact on Mesopotamian civilization apart from changing the techniques of warfare.

At about 1200 BCE, the Hittite empire collapsed. This 1200 BCE is actually a time when many other large empires and cultures based around the Mediterranean sea are either weakened or also collapsed. This is called the Late Bronze Age Collapse, as 1200 BCE is the time separating the bronze age from the iron age.

Around 900 BCE, the city of Ashur rose into even greater prominence to establish the massive military machine of the Assyrian Empire that lasted till about 600 BCE, when it came crashing down against another city-based empire, Babylon!

From 600 BCE to about 500 BCE, Babylon rose again to establish what is called the neo-Babylonian Empire or the Chaldean Empire. This is a cultural high point for the Mesopotamian civilization.

From about 500 BCE, Mesopotamia became a part of the larger Persian Empire and after the conquests of Alexander the Great around 300 BCE, it was a part of the larger Hellenistic world. Then, it oscillated between the Roman Empire and the Parthian Empire; and had a subsequent oscillation between the Chrisitian Byzantine Empire and the Persian Sassanid Empire, to be Christianised first and then Islamised later.

A brief timeline is shown below:

Bilingualism and Civilization

A very important feature that affects the very foundations of Mesopotamian civilization is its bilingualism. The early city states in the south of Mesopotamia, in the region of Sumer, spoke Sumerian. As described in the previous section, it is a language isolate - which means that it is not related to any other languages that we know of and hence is not a part of any language family. But as Sumerian culture spread northward, we also saw that eventually, the northern cities like Akkad captured the southern city states, and there was a huge migration of northern peoples to the south. The language or more precisely, the group of dialects spoken in the northern region which included Akkadian (spoken in Akkad), Babylonian (spoken in Babylon) and Assyrian (spoken in Ashur) - these all belong to a language family called the Semitic language family. The Semitic languages include other known languages like Aramaic and famous languages now known which include Hebrew and Arabic.

Due to the migration of Semitic speakers to the north, one finds that Sumerian died out as a spoken language around 1800 BCE. But even though Sumerian died out as a spoken language, one finds that it still served as an important language for writing and liturgy. One sees an extensive bilingualism amongst the literate class and the northern Akkadians continue to revere Sumerian as a sacred language and use it in parallel with Akkadian.

It should be noted that linguistically, Sumerian and Akkadian completely belong to two entirely different language families - the former is a language isolate and the latter is in the Semitic family related to Hebrew and Arabic. It is imperative that we understand some basics of the architecture of the grammar of these languages to see how different they are and will be integral to understanding the literary aspects of the Mesopotamian culture.

Sumerian is what is technically called an agglutinative language. Dravidian languages and Turkish are other examples of agglutinative languages. What exactly is meant by agglutination is that words are built by adding up a series of endings to the root syllable(s) that remain constant. For example, consider the following words in the Tamil language.

seydān = he did

seyd(u)irundān = he had done

seyd(u)irundānenil = if he had done

This words are made of the following invariant parts.

SEY-dān

SEY-d(u)-irun-dān

SEY-D(u)-irun-dān-enil

Here, the part SEY is the root part of the word that means “to do”. In every other word that has got to do with doing, it will remain constant as you see here. The other parts convey tense and mood. The functions of them are given below.

dān = this is the third person masculine singular ending for past tense [he —past tense]

d(u) = absolutive marker that signifies the completion of the action for perfect tense

irun = auxiliary verb that means “to stay”

enil = conveys hypothetical mood of “if ___”

So such languages are called agglutinative languages, where the roots and other grammatical endings are constant and the word is built together like how a building is built by fitting bricks together.

Consider on the other hand a language like Saṃskṛta. It also has a root syllable and endings but it is not agglutinative because things inside the roots also can change to convey grammatical information. Consider the following pairs of Saṃskṛta words.

akarot = he did

kṛta = done

These can be broken down as:

a-KAR-ot

KṚ-ta

a = initial augment for past tense

ot = third person singular suffix for past tense (he, she, it____)

ta = past participle suffix

We see that the root does not remain constant in all derivations of the verb. The past tense uses KAR whereas the past participle uses a weakened form KṚ. We see that the two are different although related. Saṃskṛta grammarians indeed recognise three such types of vowels inside the root as it passes through various derivations. They also give rules for under what grammatical derivations, what type of vowels will manifest inside the root. In Saṃskṛta and other Indo-European languages, verb roots are always made of exactly one syllable (optional_consonant+vowel+optional_consonant). The consonants stay put for most of the time and the vowel, although changing, changes only in three possible ways.

Semitic languages like Akkadian and Arabic take one step further. The vowels can change into any type. The roots are made of three consonants here without any vowel. Consider the three consonants K-T-B in Arabic. They convey a core meaning of writing. But look at the following words related to writing related in Arabic.

kataba = he wrote

kitāb = note book (object of writing)

kātib = writer

maktab = writing desk

maktaba = library

maktūb = written

One sees that three consonants K-T-B in all of the above words do indeed stay put but the vowels in between can take through all ranges of variation and can even be skipped. There are also prefixes (like ma) and suffixes but one also sees vowel variations inside the roots in the gaps between the three consonants.

So, Sumerian was like Tamil (what scholars call agglutinative) and Akkadian, Babylonian, Assyrian were like Arabic (what scholars call synthetic). They are linguistically very different both in terms of roots, their nature and grammatical structures.

But did the Mesopotamians view them as distinct competing languages? Actually due to the extensive bilingualism and since Sumerian was regarded and preserved as a sacred language even after it ceased to be spoken, the average Mesopotamian person thinks of Sumerian and Akkadian as twin languages and completely culturally equivalent! Every Sumerian word was thought to be exactly translatable to an Akkadian equivalent. (No, there was not a Dravidian-Aryan like separatist movement in this civilization!). The same cuneiform script that was used to write Sumerian first, was also used to write Akkadian and eventually so many other unrelated languages like Hittite, Saṃskṛta (a treaty between Mittani and Hittite kingdoms contains references to Vedic gods written in cuneiform), Elamite and also served as the inspiration of the script of the Old Persian language, the language of the Persian Achaemenid Empire that conquered Mesopotamia. In fact, this was what helped scholars to decipher the cuneiform script even though it fell out of use by the first centuries of the common era.

The Written Word: How Cuneiform Works

A very important aspect of Mesopotamian culture is its writing - they attached a huge importance to writing soon after they developed into a full fledged civilization. It is impossible to understand the worldview of this civilization without appreciating the bilingualism and its writing script - the cuneiform.

Cuneiform initially started off as a pictogram - a picture of water like 💧 representing water - much like our whatsapp emojis. This was in the very beginning stages where these pictograms were used for accounting - to keep track of what and how many of what were bought or sold. Then, these pictures expanded to cover abstract concepts and ideas using homophones - for example, in English, if we represent the word MEET by the emoji of a flesh 🥩 (MEAT which sounds same as MEET). This earliest stage is the pictograph stage. Then, slowly as the use of writing was expanded to include inscriptions, the pictures simplified to abstract shapes and they directly began to encode the word that they represent in the spoken Sumerian language along with the sound that it was pronounced with, in the spoken language. Since Sumerian was an agglutinative language with mostly single syllable root words, many of the symbols for these words also came to be understood as encoding syllables. But the correspondence between sounds and script was not always exact and would get quite creative sometimes. How this happened is explained by a pictographic emoji system that I introduce below. Note that this is just a rough idea of how the actual scripts work - there are lots of intricate details that I am skipping over:

For example, consider the following sentence in English:

King Henry is going to conquer England

Now, let me convey this by emoji writing as:

👑 🐔 🐍 🏃 ✒️ ✌️ 🌽 🍦 ✒️ 🟫

Let me propose a decoding as follows:

Sounding the first emoji, I see it is a crown, followed by a picture of a hen that I sound as HEN. The crown emoji can sound KING. Seeing the HEN emoji, I hypothesize that it is a king’s name starting with the sound HEN - and given the context of English kings, it does not take long to figure out that it must be Henry. Next, we have a snake. Snake produces a hiss sound and hence maybe that represents the word IS. Next, comes an emoji of a man running followed by the nib of a pen. The man running can be thought to represent the word GO pictorially and the nib can represent INK that sounds close to ING and hence we have GO+ING=GOING!! Next, comes the number 2 that in this case can represent the word TO which sounds exactly like the word 2. Next, we have the emoji of a corn and curd. This sounds like corn-curd which approximates CONQUER in this context. Next, again comes the INK followed by a brown emoji that symbolizes LAND and hence this may be INK-LAND which closely approximates ENGLAND.

This was how roughly Sumerian cuneiform worked. Sometimes, the symbols represented entire words like 👑. Other times, they may represent not the word but the sound or syllable that approximates it like ✒️ for the -ing ending in present continuous tense or the corn emoji representing the syllable CON.

Some other times, the sign may represent just a clue to determine what exactly the word is. For example, consider the emoji ✒️ once again. There was this god called Ing in English paganism. So, to convey that ✒️ conveys god and not a grammatical ending -ing, I might use a sign to distinguish the category of gods. So, I can have ✒️ 🙏 to mark the word that represents the God Ing, with the 🙏 to denote the category “god” but not contributing to the actual pronunciation.

The emoji ✌️ similarly can convey either the numeral “two” or the preposition “to” or the conjunction “too”. One may use mere context or special emojis of category to distinguish between the various uses. Also, even when syllabic, the same emoji can indicate slightly different pronunciations - for example, the emoji ✒️ can represent the syllable and the word “ink” but when with verbs or other emojis, can modify to represent the sound “ing” and hence it has two context dependent phonetic values - ink, ing.

The emoji 🏃 can mean either “go” or “run” and hence can represent both of these sounds. Also, the same syllable can be represented by different emojis. For example, the word “bigot” can be split as “bi-got” and can be represented as “🐝🐐”, thereby approximating “bigot” as “bee-goat”. Or I can split it as “big-ot” and can represent is as “🐷🛖” which approximates the same word by “pig-hut”. Notice that one requires immense command over the spoken language to figure out what exactly these emoji style readings mean as neither the value nor the nature of the signs is not fixed but varying around a core.

Seeing 🐷 can prompt us to render it as strictly “PIG” and seeing 🛖 can prompt us to make us to render it as “HUT” but it takes intuition and sense to figure out that “pig-hut” actually approximates “bigot”. So, the sign 🐷 is technically multi-valued - it can stand for many syllables and only in combination with other signs, can we determine how exactly it is rendered.

Reading cuneiform for Sumerian is pretty much like this except that there is an additional level of complication - the symbol that represents the sounds pig/big which was 🐷, no longer looks like a pig but something abstract that in its physical form, has lost any resemblance to the animal “pig” and it has to be learnt simply as an abstract sign that is multi-valued which can represent “pig/big/bik” and so on. One has to practice with lots of words and texts to read in this system. The pictures in the initial stages in the evolution, soon simplified to abstract logographic-syllabic cuneiform script.

So, we have the following features about cuneiform that were illustrated by the previous example:

- A sign can represent either a syllable or a word or a category marker.

- If representing syllables, the same sign can represent many syllables and its exact sound can be decoded only by reading the signs next to it.

- Same word can be represented using multiple signs.

- A single syllable can be represented by multiple symbols and a convention has to be learnt as in what symbol needs to be used as a part of what word.

Now that we have learnt how to represent English in an emoji language which gives us an idea of how cuneiform reading and writing works for the Sumerian language, we now have a further added layer of complexity. The cuneiform script initially was used to encode the Sumerian language. Soon came a bunch of Akkadian language speakers whose language is completely different from Sumerian!! The Akkadians now ask Sumerians “hey dude - your writing system is cool - we want to use this for our language too”. So, this cuneiform script was used for encoding Akkadian.

Let us imagine how this works using the emoji language. We designed it for English - each character either represents a word or a bunch of syllables or an identification marker. Let us say we now want to write Hindi using this script.

Let us say I want to encode the following Hindi sentence using the English emoji language that I had designed so far:

राजा राम ने रावण को हराया

Consider the following representation:

👑 🐑 ❌ 🛶 🚌 🐮 🦱 👁️ 🗣

I decode this as follows:

👑 = represents the word “king” directly in its meaning here which in Hindi is राजा

🐑 = represents the sound “ram” which is a synonym for “lamb” in English and now in Hindi captures only the sound of the word राम and has lost all association with the English meaning

❌ = represents the sound “no” in English but in Hindi, represents the sound of the word that acts as the past tense marker which is ने

🛶 🚌 = represent the English sounds “row-van” which in Hindi, approximates the sound of the Hindi word रावण

🐮 = represents the English sound “cow” which approximates the sound of the Hindi word को

🦱👁️🗣 = represents the English sounds “hair-eye-aah” which approximates the sound of the Hindi word हराया

So, here we see that something complicated is happening here when we write like this. Signs like “🛶🚌” and “🦱👁️🗣” have lost their meanings associated with them in English (they no longer convey rowing, vans and eyes and so on) and only their English sounds are used to approximate the sounds of the required Hindi words (row-van is used to approximately spell रावण). On the other hand, we have signs like 👑 that in English sounds as “king” but here, does not sound any Hindi word (there is no Hindi word like किंग) but just capture the meaning of the English word associated with the sound “king”.

This was how it felt when cuneiform was used to write a new language - Akkadian. Some cuneiform signs represented directly, the meanings conveyed by that cuneiform sign in Sumerian but other signs lost their Sumerian meanings and were used to just sound Akkadian words. Except that the signs are abstract and do not have any resemblance to the words that they sound in English. Now, you may ask the question - suppose I want to write an Akkadian word X in cuneiform. I have two options:

- First: I can translate the Akkadian word to Sumerian equivalent - say X’ and then use the sounds of the Sumerian X’ and represent it in Sumerian. (eg. राजा = 👑 )

- Second: I can sound the word X in Akkadian and let’s say it has the syllables “s1-s2-s3”. I can find the closest Sumerian words that sound like s1,s2,s3 and use the corresponding Sumerian symbols for the words that sound s1,s2,s3. (eg. हराया = hair+eye+aah = 🦱👁️🗣)

Which option to follow for what words in what types of situations and hence required immense practise of writing and reading and a thorough proficiency in the spoken languages of Akkadian and Sumerian.

The cuneiform tablet pictured above is from Iraq Museum, narrating the Mesopotamian epic of Gilgamesh, to be seen in detail in the next article2.

If you think that this writing system is too complicated for an ordinary human being to master - this is almost exactly how the writing system of the Japanese language works. The Japanese language has syllabic symbols that represent only sounds but also contains Chinese characters that represent meanings of full words and the written language is a mix of both the scripts.

A Dictionary is Not Literature - Or Is it

The cuneiform script and the bilinguality in Sumerian-Akkadian is so integral to Mesopotamian culture that their entire philosophy and worldview is based on this process of writing and reading. Let me ask the following questions:

- What is the first greatest literature that the English language has produced?

- What text should one start with to first read in order to get a feel for English culture?

- What text is the trademark of English culture?

- What text forms the basis for English culture and its people?

One may have lots of answers to the following questions - the Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf, or Shakspeare, or the King James Bible. But if some were to answer “The New Oxford English Dictionary” for all of these questions, how strange and weird would it be? Yet this is the closest analog in describing the situation of the Mesopotamian civilization. The first greatest works that were produced are bilingual dictionaries from Sumerian to Akkadian and they form the bases for its civilization and its intellectual thought. One main factor that might have caused this phenomenon is the extensive bilingualism in Mesopotamia between Sumerian and Akkadian - even though they were structurally and linguistically of different natures, they were considered as twin languages and equivalent languages from a civilizational point of view. When Sumerian became dead as a spoken language and began to be used only in restricted situations, formally training scribes in that language became necessary and hence dictionaries were created in order to facilitate mastering Sumerian for people who otherwise spoke Akkadian in their daily life. But the way the words were represented tells a lot about how the Mesopotamians thought about their writing, their language and even the world.

Even scholars working in Mesopotamian literature ignore the exhaustiveness of the dictionaries that were produced. No other civilization began producing such exhaustive lexicographic material almost immediately after it started writing. No other culture in this world has produced a dictionary soon after it began to write and no other culture considered it central to its worldview. In fact such an extensive Sumerian to Akkadian dictionaries only have enabled scholars to decipher the Sumerian language since it died long ago as a spoken language and has no modern living languages related to it. More about it in the appendix section where I discuss the decipherment of the cuneiform script.

In Egypt, where writing began almost the same time as it did in Babylonia, word lists were rare and were composed much later than the moment of script invention; the earliest clear example is from 1900-1800 BCE, and the more extensive ones from later in that millennium. Ancient Greece developed lexicography only in the Hellenistic period (approx 300-100 BCE), and it was in the late first century BC that the Roman grammarians like Marcus Verrius Flaccus collected a massive compendium (only fragments are preserved today) of Latin words with meanings, which led to successive lexicographic traditions. In Saṃskṛta, thesauri of difficult words in the Vedas originated late in the first millennium BCE only which is much later than the birth of Indian civilization. Amarasiṃha, the author of the most complete of the list of Saṃskṛta nouns, the Amarakoṣa, is said to have lived in the fourth century AD. In China, which was also extensively a literate civilization, the first repertory of words comes about around the third century BCE. All these works were collections of words intended to explain difficult words or archaic words in highly valued ancient texts. They did not aspire to collect together these languages’ full vocabularies. The Islamic Middle East may be the earliest culture after Babylonia to explore lexicography in full. The Arabic term for it, kāmūs, confers the idea of exhaustiveness, and already in the eighth century ad the philologist al-Khalīl ibn Ahmad produced Kitāb al-ʿayn. But still, this was much later and did not hold any level of importance as it did in Mesopotamian civilization.

The earliest preserved word lists from Babylonia may not have been complete in their coverage of the words used in contemporary and ancient writing, but certainly by the early second millennium BC the lexical collections were gigantic and seem to have tried to record every existing word in the Sumerian language. What is surprising about these lists is that they not only contain commonly used words and important words but also rare and exotic compounds, such as ki-ta-g̃eštu-g̃u, that specifically means the lower part of my ear. Even more, the compilers of lists made up fantasy words that never appeared outside this type of text and had no practical use at all3. Some scholars even argue that some smaller dictionaries were also given as exercises to be written by the student! Imagine your school homework is to compose a mini dictionary - how would you have felt?!

In this section, I will briefly convey how dictionary making was not merely a time pass activity for the Mesopotamians but it was an intellectual activity aimed to foster a deeper understanding of the world. For understanding this, one should analyze how these scribes organized entries in their dictionaries - there was not a standard alphabetical order for cuneiform signs. There were two overarching principles that governed the order of the entries. One was overall semantic and thematic - words that fell under the same category were listed together in orders of decreasing importance - for example, animals were placed together with separate sub categories for domestic and wild animals. But this order was frequently broken to include words that look like each other in script together and also to include words that share a common sub-element in a compound. This for example would mean putting entries for “fireman”, “firefly” together with the entry “fire”. Note that this involved words that are similar in their written form. But sometimes, phonetic and semantic similarity also played a role in the ordering of words. Also, different scribes could prioritize different principles differently for ordering purposes.

From Dictionary to Grammar

The first intellectual inquiry this stimulated was to study the nuances of words in various contexts. By placing words with related signs and with common sub elements together even though they didn’t share the theme under interest, semantic clarity was attained. For example, imagine the word “under” followed in the dictionary by the entry “understand”. We know that even though understand contains under as a morpheme, the separate semantic theme of “under” vanishes in the compound word “understand” - to understand is nothing related to standing under. Also, by listing all the possible forms of the word, grammatical clarity was obtained - for example, by listing “sing, sang, sung, sings, singing, song” together, it will prompt us to think where exactly which form of the word is used and this is what grammar is all about. Also unlike modern dictionaries that listed mere words, these dictionaries listed noun phrases and compounds too like having separate entries for “horse”, “white” and “white horse”. In this process, even from the very early stages of lexicography, the scribes inserted purely made up words that no one saw in their lives. This enabled the scribes to understand the full morphology and the grammar governing the phrasal relations in the language.

From Dictionary to Poetry

Exhaustive lexicographic lists also stimulated poetry as they revealed clearly the alliterations and rhymes of related words which could be exploited in composing poems. Such parallelism in structure and meaning can be seen in the poetry of all languages and exhaustive lists of a theme of items in a rhyming manner too occur in the poetry of all languages, but it becomes easier to spot and exploit when one constructs an exhaustive word list. For example, here is a Sumerian poet who lists all the weapons possessed by the Mesopotamian god Ninurta4. Brackets provide the Sumerian pronunciation of the last word of each stanza which stands for a weapon so that the rhyming can be appreciated. Uncertain pronunciations are given in capitals and uncertain meanings are denoted by question marks.

On my right, I bear my Šar-ur (šarurg̃u).

On my left, I bear my Šar-gaz (šargazg̃u).

I bear my Fifty-toothed Storm, my heavenly mace (udzuninnug̃u).

I bear the hero who comes down from the great mountains, my No-resisting-this storm (udbanuillag̃u).

I bear the weapon that devours corpses like a dragon, my Agasilig axe (agasiligg̃u).

I bear the alkad net of the rebellious land, my Alkad net (alkadg̃u).

I bear that from which the mountains cannot escape, my Šušgal net (šušgalg̃u).

I bear the seven-mouthed mušmaḫ serpent, the slayer, my Spike (?) (DUB.GAGg̃u).

I bear that which strips away at the mountains, the sword, my Heavenly dagger (g̃iriannag̃u).

I bear the deluge of battle, my Fifty-headed mace (šitasag̃ninnug̃u).

I bear the storm that attacks humans, my Bow and Quiver (panmarurug̃u).

I bear those that carry off the temples of the rebellious land, my Throw-stick and Shield (ilargurg̃u).

I bear the helper of men, my Spear (g̃išgiddag̃u).

I bear that which brings forth light like the day, my Obliterator-of-the-mountains (kurrašururg̃u).

I bear the maintainer of the people in heaven and earth, my The-enemy-cannot-escape (erimabinušubbug̃u).

I bear that whose awesome radiance covers the land, which is grandly suited for my right hand, finished in gold and lapis lazuli, whose presence is amazing, my Object-of-trust (g̃iškimtilg̃u).

I bear the perfect weapon, exceedingly magnificent, trustworthy in battle, having no equal, well suited for my wrist on the battlefield, my Fifty-headed mace (šitasag̃ninnug̃u).

I bear the weapon that consumes the rebellious land like fire, my Fifty-headed club (mitumsag̃ninnug̃u).

These are the analogues of the sahasranāmas of the various deities in our culture.

From Dictionary to philosophy

The development of extensive lexicography also stimulated the philosophical inquiry as to how writing and words and their meaning relate to reality. Indian civilization parallels Mesopotamia in this but instead of writing, it regarded the spoken sound as being efficient and the Indian linguistic tradition studied the relation between the spoken language and reality. Enumerating the exact possibilities of various Sumerian words led to two important phenomena:

- It rendered the structure and semantics of the Sumerian language completely clear, unambiguous and transparent.

- It stimulated the Mesopotamians to use this “perfected language” (Sumerian is the ancient Middle Eastern Samskṛta?!) to classify and analyze reality (see in the coming sections)

Jack Goody writes:

The extent of this listing activity is associated by Landsberger with the nature of the Sumerian language; because of its transparent and unambiguous structure, it was suited to classifying the world. I would rather argue that it was the lists that helped to make Sumerian unambiguous, that the influence of writing on the use of language was more important than that of language on the use of writing.

From Dictionary to Reality

We saw that Sumerian word lists enumerated many rarely used words and even coined imaginary words in the attempt to be exhaustive. The lexical lists possessed a very high degree of specificity - for example, they listed more than 300 vessel types, 181 varieties of sheep, and so on. The differences made theoretical sense in the lists, but they were not useful in reality. There was much less specificity in the records of daily use (which are also abundant from the archaeological record in Mesopotamia) than in the lexical texts. One might be tempted to think that the literate scribes were living in an elite ivory tower, oblivious to reality but these were the same people who were called for maintaining the accounts of practical usage. The question then that is to be asked is how did these people view or handle the dissonance between their written sophistication and their practical uselessness? Did drafting these lists as a part of their education make their minds more attentive to minute details even if unnecessary? It turns out yes - these people were very attentive to details when it came to classification - for example, They categorized sheep and goats meticulously, including aspects of how they were fattened5:

barley-fed, top quality ,first grade;

barley-fed, top quality, next grade;

barley-fed, third grade;

barley-fed,

grass fed

Many accountants of other ancient civilizations were not this much specific. Meticulously cataloging these details would be very useful in determining how such parameters (like how the sheep are fed) affect the quality of wool and the reason such details were being paid attention to was the lexicographical motivation to enumerate and classify all possible words of the language. The Babylonian scribal class thus differentiated a level of reality that others in ancient times and later on, did not see. The lexical list can be held responsible for that.

Spoken vs Written

Indian tradition on the contrary, places primacy in the spoken word over the written word. In fact only very late, writing was used to record ancient sacred texts. Writing down a sacred text like the Veda was considered a sin for a long time as the written perishable material word was considered inferior compared to the heard word that is ethereal. The most authoritative Saṃskṛta texts in Hinduism are referred to as śruti which literally means “that which is heard”. The ancient Greek tradition too had the same opinion. Plato in his Phaedrus makes Socrates describe writing as “external marks” that do not lead the reader to any new knowledge but only a remainder of what he already knew. Writing is imitation - not creation - says Socrates; true knowledge is unearthed only through dialogue. Socrates also says in that work that writing is dangerous because a written message is frozen and is the same for everybody who reads it - and hence might lead to misunderstanding in many cases and unambiguous communication requires oral discourse (although ironically these words themselves have come down to us from writing only!). This view was carried forward by Plato and Aristotle as well. The Judeo-Christian tradition, like the Mesopotamian tradition and Egyptian tradition considers the written word as more prime and powerful. When Moses goes up Mount Sinai to receive the commandments from God, he gets a tablet with written commandments and not an oral revelation. This is also not surprising as the Israelites in the Bible place their ancestral patriarch Abraham to be from the city of Ur in Mesopotamia and the Israelites also were in Egypt as slaves - so clearly it is the Mesopotamian hand at work, influencing the later Hebrew tradition.

From Dictionary to Religion

The reason that the Mesopotamians considered the written word more powerful than the spoken one can also be explained by the peculiarity of the cuneiform script. Usually, a written word is more nuanced than the spoken word because of the multiple choices available in picking up a sign and ambivalence in the phonetic values of signs. As we saw, the correct value and meaning of a sign can be determined only after reading all the other signs that precede and follow it in a word. Writing in cuneiform created its own independent reality from speech and this was accessible only to a reader. This divorce might have been what enabled them to create written words that did not exist and convey different shades in meaning by selection of the exact signs. Of course custom dictated a normal convention for choosing a particular set of signs for a particular word but in cases like liturgy, prayer and divination, this was not the case - different choices could be made. In ritual and magic - more than the incantation that was said, it was the written signs that mattered in deciding the efficacy of the ritual (which is the exact opposite of the vedic karma rituals where the spoken mantras matter and not the written ones on any medium which are considered useless). The multiplicity of signs that could be chosen to write the same word was exploited by the scribes to create multiple shades of meaning for the word which were impossible to reproduce in the spoken language. These were included and explained in the lexical lists too. Let me illustrate this with a simple example6.

Akkadian rituals against witchcraft used ovens. An oven was called tinūru in Akkadian. This Akkadian word can be split in so many ways to assign signs: two of them are tin-ūru and ti-nūru. Now, in Akkadian, there is a word called nūru that means “light”. It is cognate to the Arabic word nūr that also means light as in nūr-jahān means “light of the world” (remember that Arabic and Akkadian are both Semitic languages). In Akkadian witchcraft, witches hated light and light repelled them away. So, the splitting ti-nūru was adopted with the Sumerian word sign for light being adopted to represent the nūru part of the word tinūru that meant oven and this provided a nuance in the ritual which was impossible to reproduce in speech. So, for instance, the sign for tinūru will look like “X💡” where X is a sign that had the phonetic value “ti” and “💡” is the Sumerian logogram for light that would promptly be rendered as nūru in Akkadian. This phenomenon in writing is called polysemy in technical terms where the written word conveys more meaning than the spoken word. This polysemy added a nuanced meaning in religious poems and chantings and epics that will simply be unintelligible to anyone not literate in the full range of the cuneiform script. This polysemy also provided many connections and hermeneutical justifications of the efficacy of gods and rituals and gave hidden insights into their characteristics.

Note that to understand and use this polysemy efficiently, one needs to master the full range of the cuneiform scripts (not just the signs that represent syllables) and also complete bilinguality in Sumerian and Akkadian so that upon seeing a sign like 💡, one should remember that in Sumerian, this sign represents so and so sound that means “light” which translates as nūru in Akkadian and to read it out as nūru. This is where the lexicographic tradition helped. This rich and gigantic lexicographic tradition survived for three millennia and would have provided deep meaning to the peoples of this culture. All of these gone away to dust with the advent of Christianity and Islam!

We will pick up from here in Part 2 of this piece, where we shall explore the law codes of Mesopotamia, and delve a little deeper into their religion - their temples, gods and heroes along with their influences in the later Hebrew civilization that emerged in the Levant that is reflected in the texts of the Jewish Bible (called as the Old Testament by the Christians).

References

- Old Sumerian Temple

- Gilgamesh and Aga

- Van De Mieroop, Marc. Philosophy before the Greeks: The Pursuit of Truth in Ancient Babylonia (pp. 36-37). Princeton University Press. Kindle Edition.

- Van De Mieroop, Marc. Philosophy before the Greeks: The Pursuit of Truth in Ancient Babylonia (pp. 74-75). Princeton University Press. Kindle Edition.

- Piotr Steinkeller “Sheep and Goat Terminology in Ur III sources from Drehem”, Bulletin on Sumerian Agriculture 8 (1995) 49-70

- Van De Mieroop, Marc. Philosophy before the Greeks: The Pursuit of Truth in Ancient Babylonia (p. 81). Princeton University Press. Kindle Edition.