Swarnakamalam and the Value of the Performing Arts

31 October, 2022

1200 words

share this article

Most connoisseurs would readily agree that upon reminiscence, Telugu film of the seventies and the eighties, especially the work of the “Kala Tapasvi” Kasinathuni Vishwanath, evokes an unreproducible nostalgia and has a certain sempiternal quality to it — a longing for a time we perhaps have not known personally, yet resides close to our hearts. In his career spanning multiple decades, we see the elevation of cinema to the level of a fine art, its rising above the mundane and almost vulgar visuals that the rest of the industry tended to produce — through the rooting of his cinematic productions in the ethos and aesthetics of Hindu traditions and Dharma.

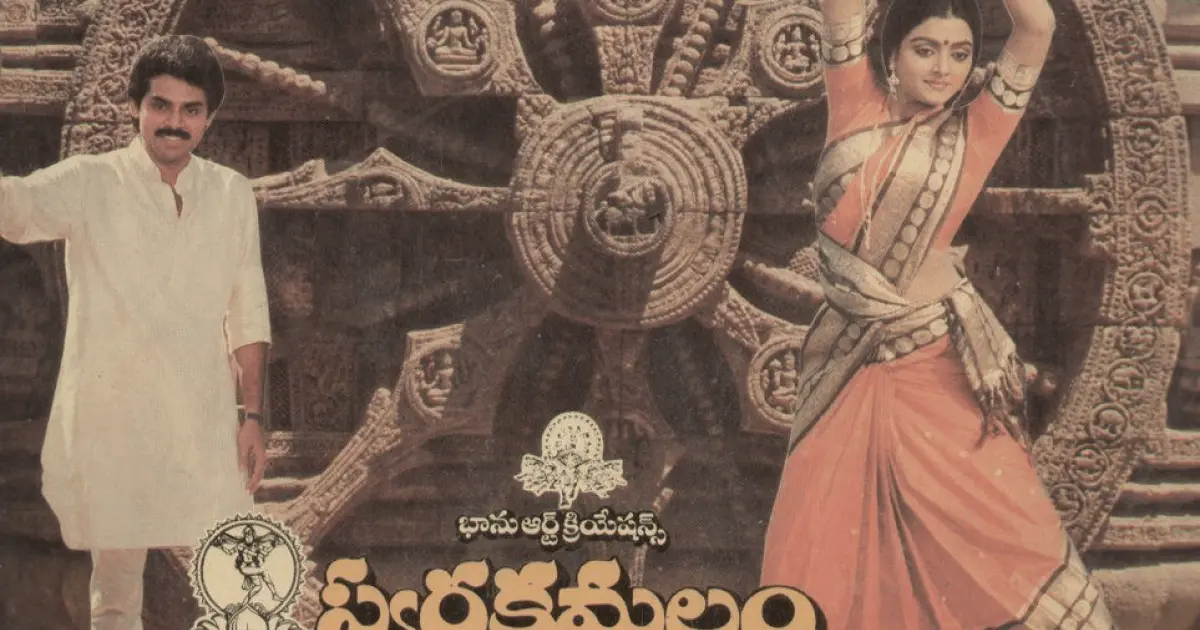

Swarnakamalam (lit. the Golden Lotus), released in 1988, was a testament to K. Vishwanath’s passion for the Indian classical arts. The mid-to-late 20th century saw a disassociation of specialised temple dancers (devadāsis) from temples, through attacks from missionaries, the colonial disposition, and the puritanical section of Hindu society — and consequently, a sharp decline in its institutional support. Swarnakamalam, therefore is K. Vishwanath’s attempt at cultural revivalism, the vivid and creative portrayal of his recognition of the theological and sacred aspect of dance which had been fading fast into oblivion, especially in the face of the introduction of contemporary evolutions in music and dance. For his exemplary body of work, K. Vishwanath was rightfully conferred multiple prestigious national awards, including a Padma Shri in 1992 and a Dadasaheb Phalke Award in 2017. Sharon Lowen, the Odissi dancer that inspires the protagonist Meenakshi in the film, wrote in a 2017 op-ed that when she is asked about starring in other films, she says that working with any other director would be a step down, and therefore wouldn’t do so — her forte anyway being in traditional dance performances rather than acting.

Swarnakamalam features a young dancer, Meenakshi, played by Bhanupriya, who does not perceive the value of her craft, Kūcipūdi. The clash between traditional values, that have brought her father nothing but penury, and the enticing modernity of the eighties and the promise of wealth — is portrayed as the leading actress’ rejection of and disdain for the traditional art form that had been taught to her by her father, and her enamor for a “modern” job and lifestyle. It is not until her dashing young neighbor, Chandrashekar, played by Venkatesh — a local billboard painter and connoisseur of her dance — recognizes her talent and gently nudges her to appreciate the value of her art, does she come to her own realization; only at the end of this journey do they profess their love for each other.

One of the most alluring aspects of the film is a song that stands out for its lyrical genius, titled “Śivapūjaku cigurincina sirisirimuvvā” which translates to “a bell on an anklet that blossomed in the worship of Śiva”, composed by the acclaimed lyricist and poet, Sirivennela Seetharama Sastry. It is styled as a philosophical debate between the two protagonists on the eternal “tradition versus modernity” debate.

One of the stanzas offers words of advice to the heroine, disguised as poetry:

O evening beauty! For the sake of stars shining on the hood of the West, don’t embrace the darkness (night)

By becoming a dance of the dawn on the stage of the East, delight the earth by spreading light;

Let your movement be an awakening of consciousness;

Let the dormant sound of your heartbeat embody the ōmkāra

The retort from the leading lady is entirely relatable with our own struggle to justify our careers, our ambitions, and the search for greener pastures in the midst of grappling with our immense heritage and the immense weight of the responsibility to preserve it.

A plant whose own roots are akin to binding chains never ceases to await the spring..

There is boundless beauty on this earth in every direction —

Let the breeze of happiness take you there.

May a new song welcome you each day

and the moonlight symphony become your companion.

Chandrashekhar, addressing her enchantment with the unexplored, the search for new experiences and lands, praises the beauty and dance that she is gifted with, and quotes a śloka from the Bhagavadgītā to bring her attention back to what is, in his opinion, the path she is destined for — that she is blessed to have the beauty and talent to pursue.

The natural movement of your feet is in itself dance,

Your beauty is like a blossoming bud touched by the sun’s rays

The eye of sūrya witnessed your dance which is like the dawn;

And caused a hundred-petalled golden lotus to blossom in the midst of a lake in the sky.

An interjection with the following half a śloka from the Bhagavadgīta is then heard in the background: “sva-dharme nidhanaṁ śhreyaḥ para-dharmo bhayāvahaḥ” — which translates to: ‘it is better to die in the discharge of one’s own dharma, than to follow the path of another, which is fraught with danger’.

Svadharma is our personal dharma, and the Gītā attests to the fact that it is better to strive to follow our own dharma, however imperfectly, than to attempt to follow another’s. In this context, that may be construed as the dedication of one’s life to their craft, to serve as a conduit for others to experience and realize the divine through nāṭya, over being seduced by the West’s purported values. As Coomaraswamy states-

“(t)he arts in India are professional and vocational, demanding undivided service”

In this film, the dancer evidently battles with her desire to live a material life outside of the traditional art world that requires an unparalleled dedication. Clearly, the message of the song is that svadharma, and art traditions supersede any temporal pursuits, that art itself rises above the mundane, with its purpose lying in the evocation of the divine in our worldly plane. The object of art is to exalt, and the value of beauty is not just for the evocation of superficial aesthetic sensation but as an inextricable part of religious function, the symbolization and manifestation of the incorporeal divine.

Carefully crafted as an ode to dance, and tradition itself in the context of the burgeoning influence of Westernization, the film’s many traditional dance sequences set against stunning backdrops across India create an aesthetic experience like no other, virtually unchartered by the movie industry at the time. There is a certain je ne sais quoi about the song Śivapūjaku, and in fact about the whole film which forms its backdrop. The overarching message that K. Vishwanath attempts to convey is to bring us back to our roots and remind us of the value of traditions that are passed down to us, which although might not be monetizable in the modern world, enrich our soul and add meaning to our existence.

Endnotes:

- The analogy evoked in the comparison of her dance to dawn is perhaps a reference to the Ṛg Veda, which employs a dancing girl as a metaphor in the description of dawn.

- Coomaraswamy, A. K. (1980). The Sacred and the Secular in India’s Performing Arts: Ananda K. Coomaraswamy Centenary Essays.

- Translations to the lyrics are largely the author’s own, with help from her mother. Apologies in advance for any inaccuracies.