SOUL: Agriculture and the Vedas, A Textual Account

3 December, 2023

1939 words

share this article

This article is part of a larger series in partnership with SOUL Societie for Organic Farming & Research Education. SOUL’s farmers, trainers, researchers and technologists work to transform agriculture with sustainable & organic farming, mainstreaming indigenous methods like the Tara Chand Belji Technique (TCBT) of farming which embraces Bhāratīya knowledge systems. Their products and educative training tap back into agricultural methods supported by Āyurveda and Kṛṣi vidyā to provide contemporary solutions which are not only chemical- and pesticide-free, but integrated into the larger ecological balance as well. Our previous articles in this series are Introduction to the Series on Agriculture and Introduction to Āyurvedic Text on Agriculture.

Evidence of the extensive practice of agriculture—the discovery of furrowed fields, deposits of wheat, barley and rice husk, and the large granaries found at some sites, especially at Harappa—indicates that these preindustrial urban settlements were supported by the agricultural surplus. Together with these food crops, there is ample evidence of the cultivation and weaving of cotton.

Zaheer Baber, The Science of Empire: Scientific Knowledge, Civilization, and Colonial Rule in India (1996)

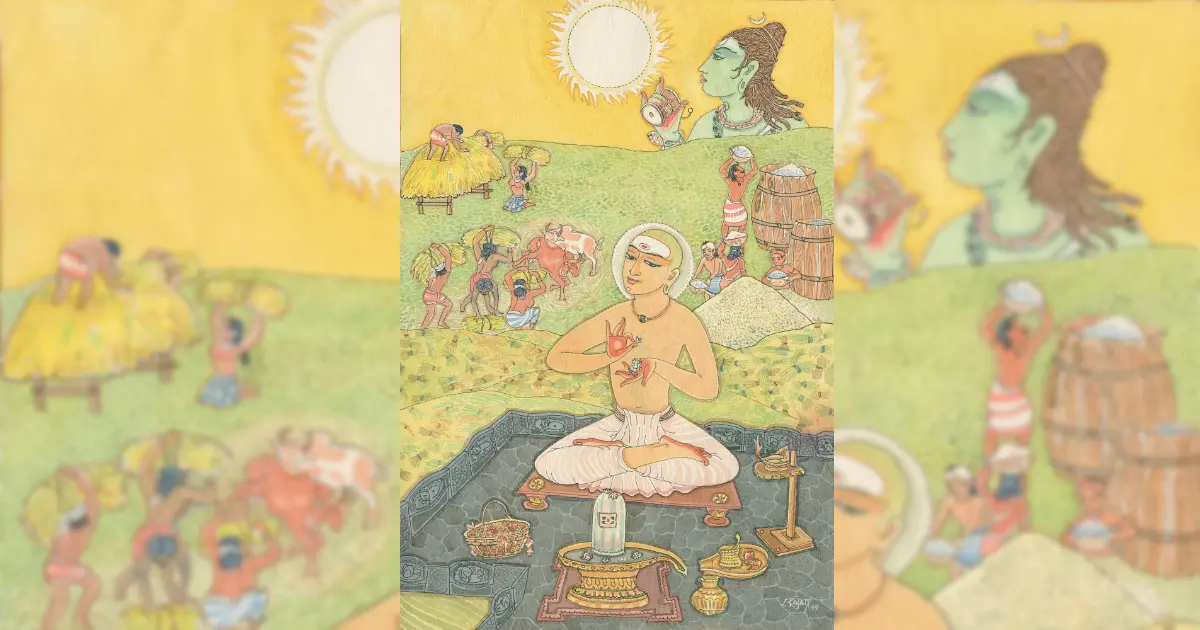

Agriculture was profoundly interlinked with Vedic society, integral to its corpus of texts, rituals, traditions, and continues to be regarded as invaluable cultural heritage of the Indian subcontinent. Vedic literature, encompassing the Ṛgveda, Brāḥmaṇas, Āraṇyakas, and Upaniṣads, serves as a repository of the ideology, convictions, and practices of the early Indo-Aryans. Within these sacred texts, agriculture, as an elemental facet of their sustenance, is accorded a pre-eminent position mention, thereby shaping both the agrarian methodologies and the socio-religious perspectives of the Vedic society. This article explores these links in significant detail.

Food is one of the basic needs of human beings — jīvanti svadhayā annena martyāḥ— and a continuous source was necessary for the beginning of civilization itself, if man was to give up his nomadism. A well-developed agricultural system is essential for this, generally done as mixed farming, with both cultivation of crops along with rearing of livestock. Vedic seers prioritize and glorify annaṃ as vai kṛṣiḥ. The Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa offers a description of four important stages of agricultural crop-production:

(i) tilling or plowing a land (karṣaṇa)

(ii) sowing of seeds (vapana)

(iii) reaping or harvesting a ripen crop (lavana)

(vi) threshing (mardana)

The Saṃskṛt terms kṣetra or bhūmi and karṣaṇa or kṛṣṭi denote people associated with cultivation, and they are found in several Vedic hymns on agriculture (Ṛgveda IV.57 and Atharvaveda III.17), along with more than two hundred references to farming, different agricultural implements and tools, irrigation, farmers, fertilizers, crops, etc. The Ṛgveda (X.34.13) states that farming is the foremost means of gaining wealth ‘kṛṣimit kṛṣasva vitte remasva bahumanyamānaḥ’. The Atharvaveda (VII.10.24) gives an account of the king Pṛthu Vainya, a scion of Vaivasvata Manu, who is credited with inventing cultivation and the identifying the process of crop production.

The Ṛgveda, has as a trove of hymns alluding to a myriad of agricultural activities, associated deities, and the merits of agricultural work and produce. Hymns venerating Prithvi, Agni, Indra, and Varuṇa underscore the imperativeness of invoking the divine to be blessed with fertility of the land and seed, abundance, timely precipitation, and safeguard against natural adversities. It encompassed a wholly symbiotic relationship, placing dependance on the Gods for human prosperity in the agricultural realm. Indra is praised as the possessor of thousands of fertile lands (taṃ naḥ sahasrabharam urvarāsāṇī). The Ṛgveda also states that due to the blazing of fire, fertile or productive land is transformed into in wasteland or uncultivable land (uta khilyā urvarāṇāṃ bhavantī ). Repeated references to the yoking of ox to the plough underscore the widespread currency of this agricultural activity. The term yūpa, which denotes a yoke, occurs frequently in the Ṛgveda.

Requesting a mighty river to release water into streamlets in the context of desire for grains, and depiction of rivers as custodians of wealth in yet another passage in the Ṛgveda point to the presence of a fairly established agrarian economy during the time. Wars, extremely important in the Ṛgvedic milieu, were fought on river banks, over differences relating to the sharing of the water which was a vital resource, seemingly motivated by a desire for grains so expressed.

The Yajurveda furnishes meticulous instructions pertaining to yāgas to propitiate a pantheon of deities, beseeching them for a flourishing harvest and overarching well-being. The Brāḥmaṇas, elucidating the rituals and their import, offer deeper insights into the agricultural practices during the Vedic era. These texts expound upon rituals such as agrāyaṇa, entailing the plowing of fields before the sowing season. Sanctity was attributed to plowing, as an auspicious marker of prosperity (śuna), and this, coupled with the personification of the plough (sīra) as a deity, underscores a certain reverence for not only the land but also the act of cultivation in itself (śunāsīrāvimāṃ vācaṃ juṣethām). After the plowing ceremony, the farmer begins to plough the field, while repeatedly saying the prayer that roughly translates to: “May the low lying lands so plowed and rich with milk and wet with honey and ghee come back to us much fertilized” (Yajurveda, 12.70).

Agriculture depends on all the five primal elements for production of crops, called the pañcamahābhūtas. Since rain is an essential, the cloud is praised as a personified deity (tak kṛṣiḥ parjanyo devatā). Without heat (tejas), growth is impossible. Air (vāyu) is essential for fertility — for its nitrogen and oxygen — and so on. The Maruts are praised as the pulverizers of soil (pipiṣvatī). Agriculture is therefore dependent on multiple natural phenomenon, as the Śatapatha Brāḥmaṇa says: sarvade vatyā vai kṛṣiḥ.

Further, while the Āraṇyakas may not be exclusively dedicated to agriculture, they underscore the significance of balance and harmony with nature. Despite their emphasis on a more contemplative and inward-looking lifestyle, these texts also broadly acknowledge the interconnectedness of all life forms in an ecosystem, including plants and animals.

The Upaniṣads delve into the spiritual realms but maintain an inherent connection with the material world. Agriculture, as a means of sustenance, is not overlooked in these texts. The Upaniṣads illuminate the cyclical nature of life and death, drawing parallels with the agricultural cycle of sowing and harvesting.

Rich agricultural symbolism permeates various metaphors and allegories, interspersed throughout Vedic literature. The metaphorical usage of agricultural imagery, such as the seed or bīja as a symbol of potential and regeneration, serves as a vehicle for conveying profound spiritual concepts in the Upaniṣads and beyond. This metaphorical appropriation underscores the profound impact of agrarian life on the intellectual framework of Vedic seers and priests. Agricultural produce such as milk, ghee and curds are elevated to heavenly status, as do rice, both whole and as pṛthuka (flattened or beaten rice). The Navadhānya or the nine grains represent the nine planets or gṛhas and are central to most Vedic rituals. They are:

- Wheat: Triticum

- Rice: Oryza Sativa

- Red Lentils: Lens Culinaris

- Green Gram: Vigna Radiata

- Bengal Gram: Cicer Arietinum

- White Beans: Phaseolus Vulgaris

- Black Sesame: Sesamum Indicum

- Horse Gram: Macrotyloma Uniflorum

- Black Gram: Vigna Mungo

In fact, during yāgas, the vigor of the flames is enhanced by incorporating pieces of coconut endosperm and the navadhānya to the conventional fire oblations.

Various Dharmaśāstras also touch upon the ethical dimensions of agriculture. The Manusmṛti delves into the responsibilities of landowners and rulers concerning fair agricultural practices, irrigation, and environmental conservation. The emphasis on safeguarding the land and its resources reflects an ecologically conscious perspective that considers the welfare of both society and the natural environment.

The connection between agriculture and Vedic literature extends beyond the confines of textual representation to permeate cultural and societal practices in ancient India. According to Witzel, Vedic texts contain “snapshots of the cultural situation of the particular period”. The agrarian calendar, replete with festivals and rituals, intricately aligns with the rhythms of planting and harvesting. Festivals such as Makara Sankrānti, the harvest festival dedicated to the sun god Sūrya, signify the transition of the sun into Capricorn, heralding longer days and the propitious period for harvesting, acknowledges the role of the sun as the source of energy for all of life itself.

According to the Agni Purāṇa, agriculture must commence under the auspices of the asterisms Punarvasu, Uttarā, Bhaga, Mūlā and Varuṇa, which should be done on Thursdays, Fridays, Mondays and Sundays or when the sun enters the sign of Taurus, Virgo and Gemini respectively. It is suggested that sowing of seeds must be performed on the second, third, fifth, seventh, tenth, or the thirteenth tithi of a fortnight or on days marked by the asterisms of Revatῑ, Rohiṇῑ, Indra, Agni, Hasta, Maitrῑ, Uttarā, Mūlā, Śravaṇa and Bhaga. Harvest of rice must be done upon the appearance of the asterism Mṛga or of those presided over by the Pitṛs or under the auspicious influence of Hasta, Citrā, Aditī, Svātῑ, Revatῑ, etc. Moreover, prior to cultivating his field, a farmer must offer oblations to the gods of the elements as follows “I offer oblation to Indra”, “I offer oblation to Marut”, “I offer oblation to Parjyañya” and “I offer oblation to Bhaga”, the gods of thunder, wind, rain and the sun respectively. Then the plough must be driven into the earth and the aforementioned gods must be worshiped for a good harvest, with garlands of white flowers and perfumes and other articles of offering, after which the god Śunāsῑra (Indra) should be invoked and worshiped.

The Vedic corpus reinforces the symbiotic interdependence between humans and nature has left an indelible imprint on Indian agricultural traditions. The concept of dharma, encompassing moral and social responsibilities, extends to the ethical treatment of the land and its resources. Traditional farming practices, including organic farming and the production and utilization of natural fertilizer, along with mixed and multi-cropping, and their modern equivalents, can be seen as a continuation of these vast ancient principles.

In summary, Vedic texts and other religious texts such as the Brāḥmaṇas, Āraṇyakas, and Upaniṣads collectively weave a rich fabric that seamlessly integrate the spiritual, ritualistic, and ethical dimensions of agrarian existence. The profound veneration for nature, the execution of agricultural rituals, the celebration of festivals and agricultural produce, and the metaphorical assimilation of agricultural imagery collectively underscore the profound understanding and integration of agriculture into the cultural and religious tapestry of ancient Indian society. This enduring connection has not only shaped the agricultural practices of antiquity but also continues to exert a discernible influence on the agricultural ethos in contemporary India.

References:

Vedic Agricultural System: The Base of Modern Agronomy by Sukumar Chattopadhyay Department of Sanskrit, BHU, Varanasi

Baber, Zaheer (1996), The Science of Empire: Scientific Knowledge, Civilization, and Colonial Rule in India, State University of New York Press

THAKUR, VIJAY KUMAR. “CONSTRUCTING THE PEASANT SOCIETY OF THE RIGVEDA.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 54 (1993): 56–67. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44142923.

Wojtilla, Gyula. “WHAT CAN THE R̥GVEDA TELL US ON AGRICULTURE?” Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 56, no. 1 (2003): 35–48. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23658557.