The Forgotten Legacy of Raja Subodh Mallik

19 July, 2023

5064 words

share this article

The man, and the setting

The address is 12, Wellington Square, Kolkata. There’s a park across the building that is named after a famous man, and the infamous Lenin Sarani is just a small walk away, being one of the few things that starkly remind you that the Communists really did rule West Bengal for 35 years!

We are standing in front of what’s left of Raja Subodh Chandra Mallik’s ancestral home. Wellington Square itself is now known as Raja Subodh Mallik Square in his honor, and so is the park.

If you were in Kolkata and walked past this dilapidated structure, surrounded by the ramshackle dwellings that are quite common around Kolkata today, you would be forgiven for not even batting an eyelid. And would it really be your fault?

This is a question that the reader of this article has the right to ask themselves. There’s no shortage of old buildings in Kolkata that are falling apart at the seams. Why should this building matter more than the others? Why should someone care about Kolkata’s heritage, especially when the city itself has developed a strange (but fascinating) relationship with its past?

If one travels to Kolkata today, one will find that in some ways, even the air of the city is submerged in nostalgia. And, at least in my opinion, this nostalgia should make complete sense to the rational observer.

Kolkata was the home of the Indian freedom struggle for most of the 19th and early-20th centuries. It was the home of the Bangali Kalpataru, a roaring cultural storm that brought the Bengali Hindu consciousness to the fore, and played a transformative role in waking up the rest of India from their indifference against Colonial rule. The city, and her people, have every right to be proud of their past and their achievements.

On the other hand, there are many who accuse the city of being too stuck in the past. The often-repeated anecdote is that every illustrious lane of Kolkata is home to silver-haired uncles, dressed in kurtas, who love to reminisce about the city’s glorious past. Kolkata is accused of clinging onto its illustrious legacy, all while its economic prowess collapses, and the state of West Bengal itself becomes a state where young people choose to migrate to other states to find reasonable employment. The city’s infamous Bhadralok, who were mostly Communists for three decades (between the 1980-2010) and are now with the Trinamool Congress, are similarly blamed for attending parties in the various British-era clubs in the city while they sleepwalk their state towards BIMARU status. The city’s past and history was even exploited by the political elite of Kolkata in 2019 and 2021 to beat-back the full-frontal assault of the BJP.

It is in this cultural context that one finds himself standing in front of Raja Subodh Mallik’s ancestral palace. But before we talk about the house itself, it makes sense to first learn a little more about the man himself. Because I am absolutely certain that the vast majority of readers of this article would’ve never even heard of him before. I certainly hadn’t, to my own shame!

Subodh Mallik was born in the Pataldanga suburb of Kolkata in 1879, seven years after the publication of Rishi Bankim’s Anandamath, and two years after (a 16-year-old) Rabindranath Tagore published the Brajabuli poem“Gahana Kusuma Kunja Majhe” under the pseudonym Bhānusiṃha. His family surname was “Bose” (Basu), whereas “Mallik” was his title. He was not born a “Raja” - it was instead a title given to him by the adoring public. Subodh Mallik grew up in Calcutta at the crescendo of the Bangali Kalpataru and graduated from St. Xaviers College, Calcutta and Presidency College, Calcutta before enrolling at Trinity College, Cambridge in 1900. He was from the famous landed Mallik family, who founded Hooghly Docking and Engineering Co. Ltd. in 1819 and ran a successful shipbuilding business in the 19th century. The family owned a princely estate, which included mansions in upscale residential areas, Baithakkhana Bazar (Calcutta’s biggest wholesale market) and land in the city’s suburbs, and in Odisha.

Family problems caused him to return from England before he was able to complete his university studies, and when he returned, he immediately delved into the nationalist movement. He came back to Calcutta at a time when political activity in India had already been heating up after the formation of the Indian National Congress in 1885. But the major acceleration to this burgeoning movement was about to be provided by the controversial policies of Viceroy George Curzon (who held the position of Viceroy of India between 1899-1905).

For the purposes of this story, there are two Curzon policies in particular that deserve further scrutiny:

- The Indian Universities Commission (1902), leading to the passing of the Indian Universities Act, 1904.

- The Partition of the Province of Bengal in 1905.

The Indian Universities Act, 1904 was meant to cut the growing effervescence of the Indian national movement down-to-size. The universities set up by the Colonial Government in the middle of the 19th century had been embraced by the existing Indian elite (in most British Indian provinces, not just in Bengal) as vehicles of social and economic advancements. But by the beginning of the 20th century, they had become noisy hotbeds of protests against the Colonial Government. Added to this were many recent private colleges that had sprung up in the city, which were run by Indians but were affiliated by the Colonial Government.

In this context, the 1904 Act was meant to cripple the influence of students in the University Senates by increasing the official (government-appointed) members in the student governance bodies. The government also followed it up by defunding and disaffiliating many of the private Indian colleges that had begun to cause a headache for the foreign government.

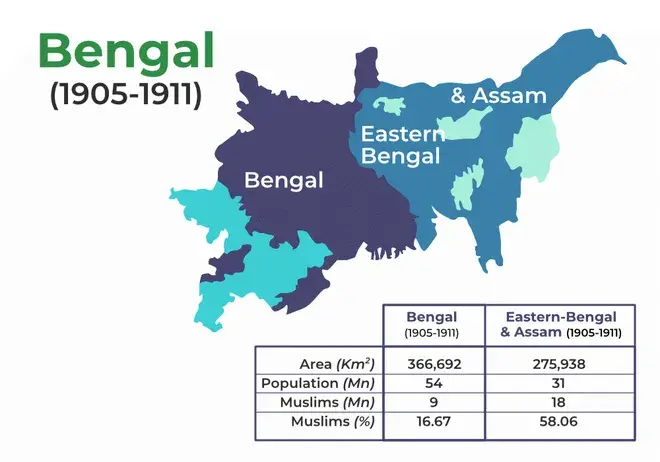

Not content with this one move, Viceroy Curzon followed it with the second blow of proposing a partition of the province Bengal on religious lines. [For the sake of the modern reader though, it is important to know that the division of Bengal in 1905 was not exactly the same as it happened in 1947. In fact, the following was the map created by the government of Curzon.]

This one-two-punch by Viceroy Curzon led to an explosion of nationalist sentiment in Bengal, with the sentiment being noticeably more pronounced in modern-day West Bengal than in the East.

It is worth exploring this difference in reaction, because in many ways, the year 1905 was the mid-point for the breaking apart of Hindu and Moslem Bengal - a process that began with the Wahhabization of the Bangali Moslem in the middle of the 19th century (like the Faraizi, Taiyuni movements, and the one led by Titu Mir) and ended with the 1947 Partition of India.

For the ease of discussion, we can call these two poles of Bengali society the “Calcutta pole” and the “Dhaka pole”. In many ways, even in 1905, the tug-of-war for the minds of the Bengali people was between these two poles. The Calcutta pole was led by a Hindu elite that rose to prominence due to British policies - most prominently Lord Cornwallis’ Permanent Settlement and also the policy of English education advanced by Thomas Macaulay. The Dhaka pole was the old Moslem aristocracy that had been patronized by the Moguls, but had fallen on hard times after the arrival of the British. All they had to bargain with now was the Moslem demographic dominance in East Bengal, something that the British and Bengalis alike had only understood the true scale of due to the British government-conducted Census of 1872 (to me it is a very poignant thing that this Census and Bankim’s Anandamath are both associated with the year 1872, which was also the birth year of Aurobindo Ghosh. It can be seen as an interesting marker in the history of Bengal). So this bubbling conflict was one between an ascendant Calcutta Hindu elite, boasting luminaries like Rabindranath Tagore, Bankim, etc. and a receding Dhaka Moslem elite, who were looking backwards rather than forward (with only a newly-acquired demographic ascendancy to bargain with). Luckily for the latter, the British Colonial government possessed a need for groups of people that could undermine the growing Indian national movement and the very idea of India’s nationhood. In the name of protecting the rights of minorities, of course!

Therefore, when Viceroy Curzon in his speech at Dhaka (February 18, 1904) implored the attendees that the Partition “would invest the Mohamedans in Eastern Bengal with a unity which they have not enjoyed since the old days of old Musalman viceroys and kings”, he was appealing to this old Moslem elite based in Dhaka.

A lot of this commentary coming from the Dhaka pole was in the form of victimhood literature. They spoke of the “discrimination” and “bias” that had been created in the favor of Calcutta, and sold (I think they believed it too) the Partition as a means of empowering the Bengali Moslem. If we read some of the major contemporary voices:

Nawab Syed Shamsul Huda: “Before the Partition, the largest amount of money used to be spent in districts near Calcutta. The best of colleges, hospitals and other institutions were founded in or near the capital of India … We have inherited a heritage of the accumulated neglect of years”.

Nawab Salimullah (the Nawab of Dhaka) in an article titled “The New Province - Its Future Possibilities”: “No one can deny that the partition has roused the entire Mahomedan community of Eastern Bengal. Many poor Mahomedan youths, who had graduated with honors, but were roaming about in search of suitable employment, are now getting prize posts, which they so highly deserved”.

So Bengal was Partitioned (for the first time). And the people of Bengal, already on the boil due to Curzon’s governance, exploded in protest. While the protests were mostly led by the Calcutta elite, it also had some notable Moslem participation from the likes of Khwaja Atiqullah, Abdur Rasul, Khan Bahadur Muhammad Yusuf, Mujibur Rahman, Abdul Halim Ghaznavi, Ismail Hossain Shiraji, Muhammad Gholam Hossain, Maulvi Liaqat Hussain, Syed Hafizur Rahman Chowdhury of Bogra and Abul Kasem of Burdwan.

And at the crossroads of these two movements - one focused on education, and the other on the more immediate concern of the Bangabhanga (Partition) - stood Subodh Mallik. In fact, since the need for a move towards a National Scheme of Education was seen as a major part of the Indian response to the Partition of Bengal, it might not even be correct to consider them different movements.

Subodh Mallik’s palatial house in Wellington Square in Calcutta became a major hub of political activity. In 1906, Mallik was among a group of leading luminaries of Bengal who founded the National Council for Education to promote indigenous and nationalist education in higher education. He also famously pledged ₹1 lakh for the foundation of a National College in Bengal at a meeting held on November 9, 1905 at the Field and Academic Club. The Council for this University was registered on June 1, 1906.

As the story goes, this was the act that earned him the title of “Raja” from Bipin Pal, the famous Indian nationalist. Pal pronounced Mallik a “Raja” from the dias in the very same meeting that was held on November 9, 1905. Later, the public freed the horses of Mallik’s carriage and pulled him in the carriage from Panthir Math to his residence at 12, Wellington Square.

Subodh Mallik was also a close partner and confidante of someone who I consider to be one of the most important figures in modern Indian history - Aurobindo Ghosh. The well-known Śrī Aurobindo, in his political avatar, was one of the most prominent names in the nationalist politics of this period. Having spent many years working as a teacher in the administration of the Gaekwad Maharaja of Baroda, Aurobindo also worked to rouse the national consciousness through his fiery columns in Bipin Pal’s Bande Mataram, a magazine Aurobindo would later come to edit himself. Subodh Mallik was the co-publisher and patron of the Bande Mataram newspaper, and the paper was edited from a room in a (different) house owned by Subodh Mallik, which is just behind the more famous house at 12, Wellington Square.

I had the privilege of visiting this second house in March 2023, where I was graciously hosted by a surviving descendant of Subodh Mallik, Mr. Kunal Mallik, who also provided me with a lot of the first-hand anecdotes that have been shared in this article. The house I visited was a beautiful British-era Bengali residential structure, with walls that whispered their history to anyone who cared enough to listen. The feeling of being in this house reminded me of this beautiful passage from V.S. Naipaul in his second India book, A Wounded Civilization:

From the lane the two establishments did not appear connected. The shop was small, its little front room and its goods quite exposed. The house, much wider, was blank-fronted, with a low, narrow doorway in the middle. Within was a central courtyard surrounded by a wide, raised, covered veranda. At the back, off the veranda, and always shaded by the sun, were the private rooms. It was surprising, after the dust and featurelessness of the lane: this ordered domestic courtyard, the dramatization of a small space, the sense of antiquity and completeness, of a building perfectly conceived.

It was an ancient style of house, common to many civilizations; and here - apart from the tiles of the roof and the timber of the veranda pillars - it had been rendered all in stone. The design has been arrived at through the centuries; there was nothing now that could be added. No detail was unconsidered. The veranda floor, its stone flags polished by use, sloped slightly toward the courtyard, so that water could run off easily. At the edge of the courtyard there were metal rings for tethering animals (though it seemed that the sarpanch had none). In one corner of the courtyard was the water container, a clay jar set in a solid square of masonry, an arrangement that recalled the tavern counters of Pompeii. Every necessary thing had its place.

As someone who is deeply inspired by Aurobindo’s political writings, it was nothing short of a pilgrimage to be able to visit the very room where the Bande Mataram newspaper was edited. And this appreciation was doubled by the knowledge that it was Subodh Mallik’s support that allowed Aurobindo to inspire the nation. When in Calcutta, Aurobindo used to live in Mallik’s house, sometimes editing the paper with Mallik deep into the night!

When Aurobindo and his “nationalist” faction (known to Shuddho history as the “Extremists”) went to Surat in 1907 to collide with the “loyalist” faction (known as the “Moderates”) of the Indian National Congress (an event now famous as the “Surat Split”), it was Subodh Mallik who bore all the expenses for all the delegates from Bengal who where attending the session.

Before working with Aurobindo in the matters of Bande Mataram and the Indian National Congress (and other, more discrete matters), Subodh Mallik had also played a crucial role in inviting the great man give up his position in the administration of the Gaekwad of Baroda, to become the Principal of the National College in Bengal. This College is, of course, (tragically) modern-day Jadavpur University. It’s been some journey for this institution, to go from being the leading light of the nationalist movement, to only entering the national conscience these days for its latest Communist student demonstration.

Jadavpur’s own website details its (based on its current status, undeserved) legacy:

Generous donations for the great cause of national education came from Raja Subodh Chandra Mallik, after whom the road on which Jadavpur University stands, is named, Brojendra Kishore Roy Choudhury, Maharaja Suryya Kanto Acharya Choudhury and others and National Council of Education (N.C.E.), Bengal proceeded with its programme. Subsequently came a princely bequest of ₹13 lakhs from Sir Rashbehari Ghosh, the legendary legal luminary.

The website adds:

Sri Aurobindo was the first Principal of the Bengal National College and among the teachers was luminaries like Rabindranath Tagore, Sir Gurudas Banerjee, Ananda Coomaraswamy, Surendra Nath Banerjee, Ramendra Sundar Trivedi, Radha Kumud Mukherjee, Benoy Kumar Sarkar, Sakharam Ganesh Deoskar and others.

Talk about an all-star faculty!

In the period between 1905-08, the atmosphere in the Swadeshi Movement was electric. As the famous historian Radha Kumud Mookerji, himself a teacher at the National College, recalls:

“..in those stirring times when the country, especially Bengal, was thrown into a whirlwind agitation over the partition of Bengal by Lord Curzon…”

“At that time Sri Aurobindo took up the personal leadership of the Revolution which ushered in the nation’s battle for freedom. Every day he would go from the Bengal National College to the evening gathering at the house of one of India’s patriotic martyrs, Raja Subodh Chandra Mullick, in Wellington Square. The gathering, by its thought and inspiration, resembled that of the French Encyclopaedists, the intellectuals who paved the way of the French Revolution…”

All this political heat was obviously too much for the Colonial government to handle. And they cracked down hard on the protagonists of the movement. Aurobindo was arrested in the Alipore Bombing Conspiracy, in which Khudiram Bose and Prafulla Chaki had attempted to assassinate Douglas Kingsford, the District Judge of Muzaffarpur. In total, 40 Revolutionaries of the Anushilan Samiti were charged with “waging war against the Government”.

Subodh Mallik was among those arrested. He was held without trial in the period of 1908-1910 and deported to prison in Almora for this period of fourteen months. After his release in February, 1910, Śrī Aurobindo paid him a visit at 12, Wellington Square. That was the last time Mallik saw ŚrīAurobindo.

It was an anticlimactic end to an incredibly fruitful relationship. The story itself is about the incredible heroism shown by two young men - Aurobindo was 33 years old in 1905, and Subodh Mallik was only 26! These brilliant young men, who could’ve easily lived out their lives as native administrators of the Colonial British Raj, decided to risk everything and fight for their country. For this, I believe they have earned their immortality in the eyes of history.

And while Aurobindo is (justly) remembered fondly and widely throughout the country, his partner-in-crime and biggest supporter has not been so lucky. And sadly, nothing embodies this more than the state of his ancestral house, the fabled 12, Wellington Square.

The House, and a story of shameful neglect

Subodh Mallik’s famous house at 12, Wellington Square is perhaps as storied as the man himself. The house was built in 1883-84, and when Subodh Mallik decided to dedicate his life to the Swadeshi Movement, this house became the center point of the entire movement.

Throughout the Swadeshi Movement, the house was frequented by nearly every famous name of the time - Rabindranath Tagore, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, the Gaekwad of Baroda, Surendranath Banerjee, Prince Count Okuma (of Japan), Gopal Krishna Gokhale, Aga Khan III, W.C. Bonerjee, Sakharam Ganesh Deuskar, Maulvi Abdul Rasool, Jyotirindra Nath Tagore, etc.

Aurobindo and Rabindranath produced many of their famous writings and other creative works in this house. It is also believed that the decision to assassinate Judge Kingsford was taken by a “revolutionary” tribunal consisting of Aurobindo, Charu Chandra Dutt, and Subodh Mallik.

Subodh Mallik’s descendent, Mr. Kunal Mallik, has described the house as such:

The house had a U-shaped structure with a garden in the middle. It had all the trappings of western civilization. The polished wooden dance floor on the first floor was later transformed into an impressive staircase. The rooms were well-prepared and furnished in western style. Wood works on the door had the anchor (the family symbol) with the letter “M” on them. Hanging from the walls were European paintings, including the world famous paintings of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart. The floor was carpeted, and chandeliers were hung from the ceiling. The library room was a big hall with bottle green furnishing and the wall cupboards were up to the ceiling surrounding the entire hall, and in the middle of the roadside wall was a big bay window. The cupboards were full of rare books. There were long verandas, and the rooms were all white-marbled.

The ground floor had a black marble floor and the walls were painted by artists who had come over from Italy. There was a large dining room where the Mallik family entertained their guests lavishly. The first wing had the baburchikhana, and the back wing had kitchens for cooking, one for the family, and the other for the deity.

The middle wing had a wooden bridge initially to connect the front and back wings, (and) was later built over. The back wing was the place where the women of the house dominated. The family deity was also lodged there. There was a strong room with iron doors and cages, where the family fortune was stored. There was also a golden tree with emerald leaves, and flowers and fruits of ruby and diamond.

There was a back door in the rear wing known as the “khirki dorja”. As per the custom of the Mallik family, newly-wed brides entered the house through this door for their very first time. When the daughters of the family were married, vegetarian meals were served on the marriage day.

Inside the front gate stood the Nahabatkhana, which was bought in a fair by Prabodh Chandra Mallik, the father of Subodh Mallik.

Once the Swadeshi Movement and the Anushilan Samiti were crushed by the Colonial Government, the protagonists went their own ways. Aurobindo was released from jail on May 6, 1909, delivered his famous Uttarpara Speech a few months later, and eventually found himself in Pondicherry, where his life took the path we know and celebrate today.

Meanwhile, Subodh Mallik spent the later years of his life in Darjeeling. His life was cruelly cut short, and he died on November 14, 1920, at the young age of 41.

After Subodh Mallik’s untimely death, the fabled family house (and many other properties) were gifted by the nephew of Subodh Mallik to Calcutta University for the purpose of being used for the “advancement of learning”. As the years went by, there was a legal dispute between Calcutta University and a durwan of the Mallik family, who illegally occupied the property.

In the words of Mr. Kunal Mallik:

It (the house) is now a property of Calcutta University, but they have done nothing to restore the property and put it to use for the advancement of learning. A signboard claiming the house as the property of Calcutta University can be seen near the house, but the rest of the house is in shambles. Ironically, the Kolkata Municipal Corporation has declared the building as a “heritage building”, as well as an “endangered” one. A house next to the building collapsed a few days ago, and everyone is afraid this historical house will face the same fate if a restoration process is not taken up immediately. We, the people of Bengal, and our next generations, will lose a very precious memory of our struggle for freedom.

A news story from Millennium Post agrees, reporting that:

Motor repair shops have come up on the courtyard. There was a massive garden which has been encroached. The Kolkata Municipal Corporation (KMC) engineers felt that if any portion of the house collapses it might lead to loss of lives to the people of adjacent houses.

The civic officials felt that a thorough restoration of the house was required. Restoration experts in the city maintained that as the building is a part of the city’s history and associated with the freedom movement, it should be repaired and restored properly.

And so, we come to today.

As of the middle of 2023, the famous house of Subodh Mallik still seems to be hostage to apathy and indifference of the square-faced bureaucrats of Calcutta University. According to Mr. Kunal Mallik, he and others working towards the restoration of this structure have tried almost everything, including petitioning politicians from all political parties, bureaucrats, university administrators, etc. to wake up the Calcutta University officials from their state of patent negligence of history. Complications have also been introduced by the legal status of the house, which has been dicey throughout the 20th century, with many Court cases and disputes, as listed out in this article in the Mint newspaper.

A Facebook group by the name of “Save a Historical Monument - the House of Raja Subodh Mallik” is run by Mr. Kunal Mallik, with 781 followers as of July 2023. According to this page, there seems to have been some recent chatter about the state of the building in Bangla language newspapers (like this article in the Anandabazar Patrika), but it hasn’t led to any concrete action yet.

So as I sit here finishing this article, I find that I am asking myself, can I do something to make a difference in this scenario? Can I get enough people on the internet to care about a monument that deserves to be preserved in its historical form for the prominent role it played in a vital movement in the freedom struggle? Should the reader from Delhi, or Mumbai or Chennai, or even in another country, care about a structure from a bygone era in a sleepy city that has seen better days?

Is there anything we can do? One thing we can certainly do is inform Śrī Sudip Bandyopadhyay, who is the Lok Sabha Member of Parliament from the area, how much we want the house to be restored. If you are a reader and can speak Bangla, it is even more important that you let Mr. Bandopadhyay know that you care about this house, and that he should do his absolute best to push the Calcutta University officials out of their indifference. The same goes for Ms. Nayna Bandopadhyay, who is the Member of Legislative Assembly for this location.

Please also consider sharing this article with anyone you know who lives in West Bengal, especially in Kolkata, and get in touch with the Facebook group listed above. This is a little piece of Indian history that is still (barely) with us, and we are capable of taking action to preserve the building for future generations. Let’s make sure we do whatever we can!

A final word has to be reserved for what seems to be the only major book written about Raja Subodh Mallik. The book is titled Raja Subodh Chandra Mallik and His Times and was released in the year 1996 by the author Amalendu De. It was published by the National Council of Education, Bengal. Any reader who is more interested in the life of Subodh Mallik should try to acquire and read the book!

বন্দে মাতরম্!