From Neglect to Nurture - An IKS Lens to the Conservation Practices of Stepwells

3 January, 2025

3547 words

share this article

इदमापः प्र वहत यत्किं च दुरितं मयि ।

यद्वाहमभिदुद्रोह यद्वा शेप उतानृतम् ॥८॥Idamāpaḥ pra vahata yatkiṃ ca duritaṃ mayi |

Yadvāhamabhidudroha yadvā śepa utānṛtam ||8||O Water, please wash away whatever wicked tendencies are in me, and also wash away the treacheries burning me from within, and any falsehood present in my Mind.

Apah Suktam - Ṛgveda 10.9

Introduction

Water, being one of the pañcamahābhutas, physically sustains every living and non-living thing in this universe; while spiritually, it is considered as a symbol of purity that not just cleanses our physical body but our subtle body as well.The Ṛgveda identifies water as a universal purifier, integral to invoking divine blessings and prosperity through hymns. In the Upaniṣads, water is portrayed as a manifestation of the “unmanifested,” representing the fundamental source of creation and the intrinsic unity underlying the cosmos. Vaidika scriptures describe the primordial state of existence as a vast cosmic ocean, from which the world emerged. Thus, water is symbolically revered as the origin of all creation, serving as the sustainer of life and the vital force of the universe2. This just begins to establish the essentiality of the facts that our human body is composed of 60% water, and mother earth as well is composed of 71% water.

When we combine the physical with the spiritual, as all things in our knowledge systems and traditions do, it gave rise to rituals such as taking a daily bath early in the morning, offering water to Śiva liṅga, partaking tulsi water as prasāda in temples and taking a dip in the natural water bodies, especially our holy rivers.

Nevertheless, in our great past, when there was a geographical constraint of such natural water bodies and rivers not reaching certain arid regions, what did the great Indian engineers do? They built huge water catchments; not mere utilitarian structures but thoughtfully crafted sustainable ecosystems, adorned with divine details so intricate that they captured the spiritual essence of a sacred dip in the holy rivers. These stepwells were known by various names in various regions: vāv in Gujarat and Rajasthan; bāolī (bavḍī, bawlī, bauḍī) in northern India; and kalyāṇī or puṣkariṇī (temple tanks) in southern India.

Origin and Brief History of Stepwells in Bhārata

The origination of stepwells can be traced back to the great baths of the Sindhu-Sarasvatī Civilization. These earliest public tanks served as ceremonial bathing grounds that were facilitated with rooms, proper drain outlets, natural purification systems, and bitumen (waterproof tar) coating.

Ruins of a great bath in Mohenjodaro3

Ruins of a great bath in Mohenjodaro3The intricate carvings on the stepwell walls and huge depths came in much later, around 200 to 400 AD, in the arid regions of present day Gujarat and Rajasthan; where both water and embellishments added life to the dry deserts, resulting in a type of temple - ‘Jal Mandir’.

The development of such large scale public tanks primarily arose from the need to have a river equivalent source of water for public use, for the population settled in arid regions and the inefficacy of pulling out water from regular wells to serve this very purpose was realized over time. Hence emerged the idea of having wells that are accessible by steps - ‘Stepwells’. Beyond their primary function, these structures served as natural coolers, mitigating the intense heat of dry summers, thus enhancing their significance in civilizational development. These stepwells were either built with locally available stones, or carved in existing rocks, and treated with natural waterproofing compounds and lime plastering. The potential sources for water were either the natural groundwater table, a nearby lake or river and the most ideal of all - rainwater.

Thus, rainwater harvesting is an age-old technique for the Indian civilizations. These stepwells were not just engineering wonders; but were also another means for culture, and hence sustenance of dharma.

The purpose of these stepwells was to provide water for day to day activities such as water supply for agriculture and public homes, bathing, washing clothes, passive cooling, sādhanā, daily prayer rituals, and ceremonies. Men and women then gathered here, everyday, fostering community building. There were no such typologies or variations seen in the pattern of building stepwells across the landscapes of India. The slightly variated was the puṣkariṇī. Although they had similar architecture, puṣkariṇīs (or kuṇḍs) were particularly built alongside a temple, for devotees to take a dip in the holy water and purify themselves before entering the temple. Some were also used for immersion of mūrtis or pūjā sāmagrī (visarjana), along with the prayers and ceremonies in the temple. Interestingly, the puṣkariṇīs in Hampi, following the construction style of that period, was built by resting one stone slab over the other in a stepped manner without any use of joineries. Certain palace complexes also had such stepwell structures, particularly for the queen’s bath; which were consequently borrowed by Mughal architecture in the form of hammāms.

Pushkarani, Hampi4

Pushkarani, Hampi4We know that wells are deep, this one knows..but then they are tall - seeing one for the first time.

Amitabh Bachchan, Gujarat Tourism Advertisement

Initially, from 2nd to 9th century, stepwells like Chand Baori in Abhaneri, Rajasthan or Agrasen Baoli in Delhi were the heightened successors of the great bath, which were characterised by an intrinsic play of the geometry of its main element i.e. the steps, along with carved pillars and walls. The requirement for a baoli in, Delhi, which is already Yamuna-accessible, is a hint that the whole of Bhārata may have faced a water crisis around the 9th century.

Later, around the 12th century, the explorative Indian craftsmanship rooted in divinity of rasa gave us marvels such as Rani ki Vav in Patan, and Adalaj ki Vav near Ahmedabad, Gujarat. These vāvs focused on temple-like, intricate carvings of various avatars of gods and goddesses, and scenes from both the Purāṇas and folktales, on the walls and pillars of each storey, rather than the geometric step patterns. Even our traditional pratice of solaha (sixteen) śṛṅgāra is depicted through carvings at Rani ki Vav; in tandem with stepwells playing a key role in the lives of women of the community. The most noticeable feature of the vāvs was their multi-storied pattern that allowed access to varying water levels in different seasons. And every storey consisted of a platform for all rituals and ceremonies, viewing galleries, rooms for changing, and storage. They are the precursors to the idea of providing changing rooms and showers next to a modern day swimming pool.

Chand Baori, Abhaneri, Rajasthan5

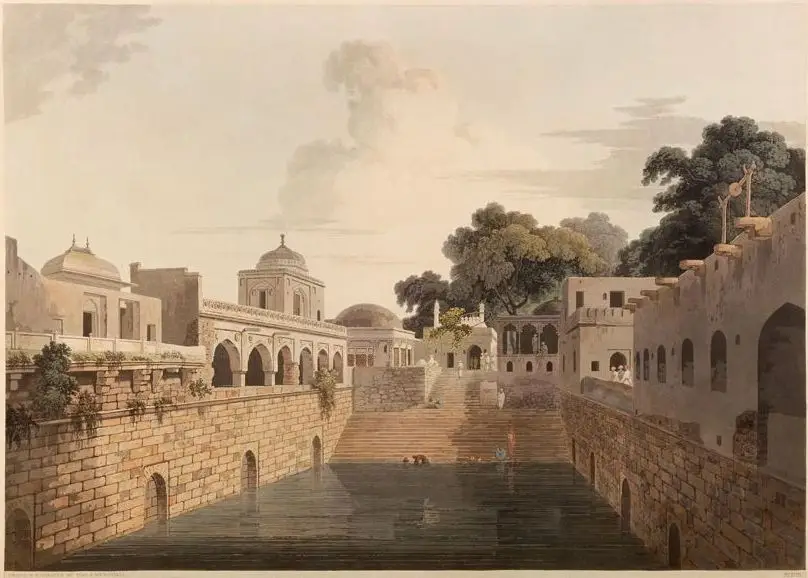

Chand Baori, Abhaneri, Rajasthan5 A baoli in Delhi from the book Oriental Scenery, 1816 which resembles Agrasen Ki Baoli.6

A baoli in Delhi from the book Oriental Scenery, 1816 which resembles Agrasen Ki Baoli.6In addition to the independent stepwells of Gujarat, Rajasthan, and Delhi, as well as the puṣkariṇīs in the southern Indian temples, the Deccan region witnessed the construction of standalone stepwells during the 17th century, particularly under the Nizam rule. A significant driver for the development of these structures may have been the recurring water crises, still experienced by urban centers such as Bhagyanagar (modern-day Hyderabad), despite the region’s abundance of freshwater lakes. These stepwells, however, exhibit a marked departure from the intricate carvings and elaborate step patterns characteristic of earlier architectural traditions, aligning more closely with the utilitarian design principles of the Great Baths. This stylistic shift likely reflects a pragmatic approach to addressing water scarcity in the context of the region’s socio-environmental challenges, which stands relevant even today.

Rani ki Vav, Patan Gujarat7

Rani ki Vav, Patan Gujarat7In the region surrounding Bhagyanagar, numerous stepwells have been identified, including the Bapughat Stepwell, Badi Baoli, several smaller tanks within the Nizam gardens, and the recently revitalized Bansilalpet Stepwell. While detailed historical records and construction methodologies of these structures remain sparse, their prevalence, coupled with local oral traditions, underscores their historical significance and utility. Presently, some villages in the vicinity have independently initiated the reuse of these stepwells, primarily for rainwater harvesting and agricultural water supply, reflecting their continued relevance in meeting contemporary water management needs.

Conservation Conundrum

The discontinuation of stepwell usage can be attributed to several factors. Key among them was the decline of civilizations and the absence of subsequent settlements in the same regions to maintain and utilize these structures. Natural disasters such as floods and earthquakes didn’t damage our robust structures, but ended up covering them in debris for no one to view and discover. Most recently, the advent of colonialism, which viewed these stepwells as a breeding ground for diseases, as a result of inefficacy to understand the underlying purification and drainage systems.

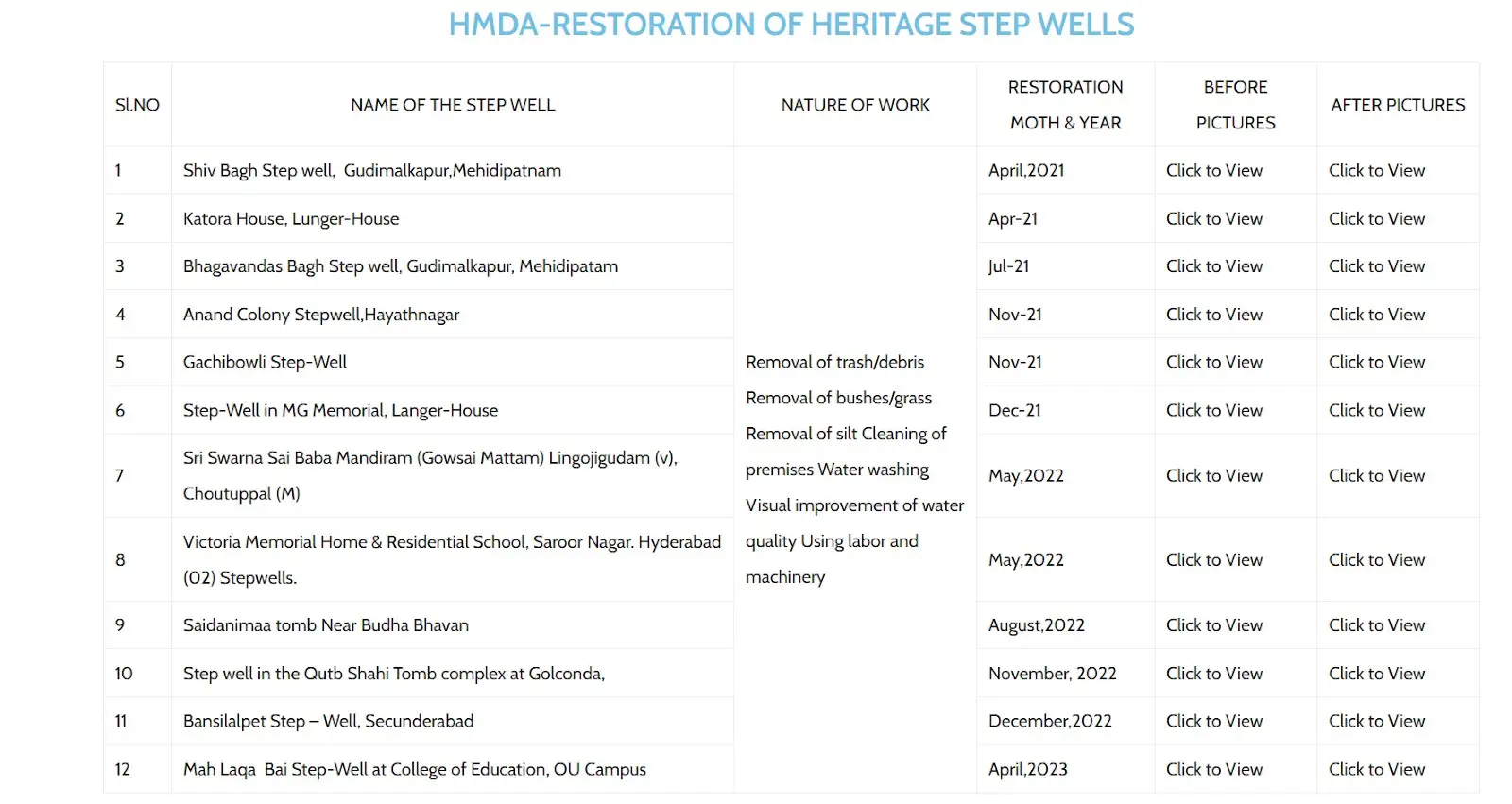

Nevertheless, after observing the recently growing public curiosity and proactive participation with these structures, the Heritage Department Hyderabad Metropolitan Development Authority (HMDA) restored about 12 stepwells in a year. They started off with the most basic steps of removing trash and unnecessary vegetation, cleaning and desilting of water and cleaning the overall premises, to at least make them accessible to the public, as a first step towards appreciating and preserving their heritage.

List of Stepwells revived in Hyderabad8

List of Stepwells revived in Hyderabad8Most of the stepwells in Rajasthan were restored and are continually preserved by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) and Rajasthan Tourism Development Corporation (RTDC). The restoration process was similar to the one mentioned above; along with reconstruction of certain broken steps and carvings, adding of new pavements and railings, and beautification of the surrounding complex. These made them yet another monument for the public to not only visit, but also a budding location for modern-day experiences such as pre-wedding shoots. Continuous cleaning of the structure as well as the water within it is done with the basic aim of preservation of heritage for future generations.

The restoration and preservation of Gujarat’s monumental stepwells, such as Rani ki Vav, follow broadly similar methodologies; however, addressing the intricate sandstone carvings of Rani ki Vav presents significant challenges. The carvings, highly susceptible to deterioration, exhibit disintegration even upon minimal physical contact. Attempts to stabilize the sandstone using modern materials and technologies, including the development of novel compounds, have largely proven ineffective due to disparities in thermal expansion and contraction, which result in the detachment of applied plaster.

Research conducted by academic institutions and organizations, including the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), has identified groundwater pressure as a contributing factor to the formation of cracks in the stone figurines. Efforts to mitigate this issue have been constrained by the structural dimensions of Rani ki Vav, which spans 12 stories in height, length, and width. According to expert archaeologists, including Padma Shri K.K. Muhammed, the preservation of these delicate carvings historically depended on their constant immersion in water, with the moisture serving to fortify the sandstone. Historical accounts suggest that the water was sourced from a nearby tributary of the Saraswati River, now extinct. The contemporary feasibility of collecting, storing, and maintaining sufficient volumes of water to replicate these conditions remains an open question.

Very recently, the mysterious rise in water level at Agrasen Baoli in Delhi paves some hope for their adaptive reuse. This led to an immediate call for action to research on its engineering - the water-supply network, what were the natural purification methods employed, and ultimately proper drainage and disposal of unclean water.9

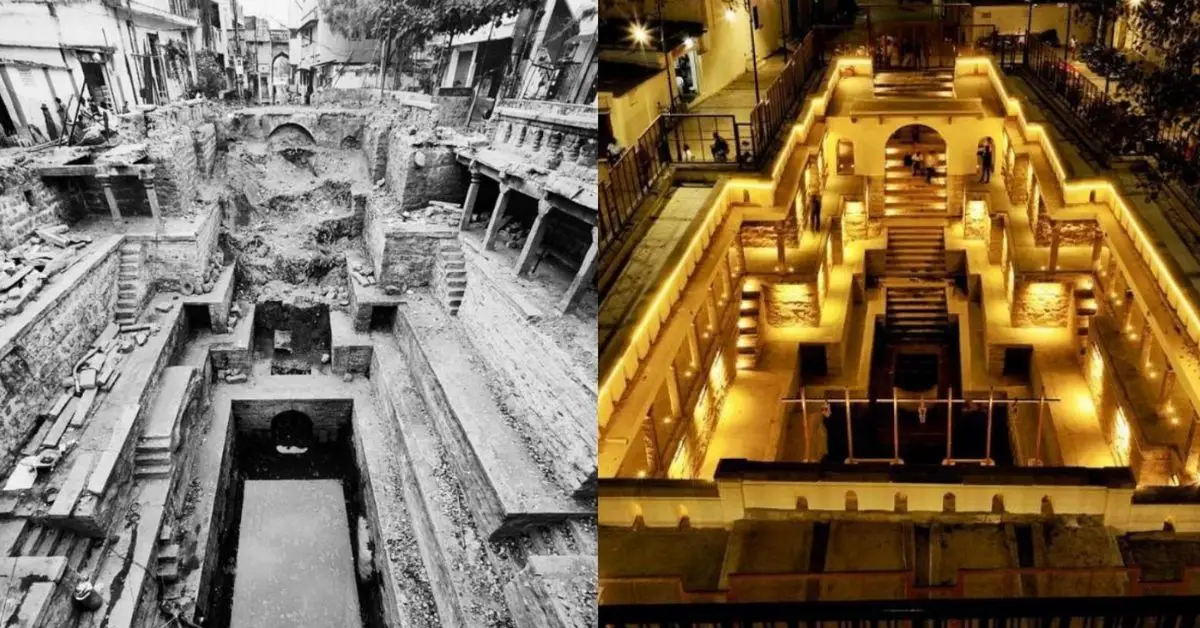

Coming to the recently celebrated restoration and beautification of the Bansilalpet Stepwell in Hyderabad marks a significant milestone in heritage conservation, transforming it into a community-centric initiative. The restoration process began with the removal of 2,000 tons of garbage, silt, and debris, followed by dewatering and refilling the stepwell with clean water. Damaged sections were repaired using traditional lime plaster, while select areas were reconstructed with cement plaster to ensure structural integrity.

To highlight the cultural and historical significance of the stepwell, a museum with three galleries was established. These galleries provide an educational experience for visitors:

- Gallery 1: Features a scale model of the stepwell, accompanied by photographs documenting its condition before and after restoration.

- Gallery 2: Focuses on water conservation, with visual displays and illustrations emphasizing sustainable water management practices.

- Gallery 3: Located on the first floor, showcases ancient artifacts uncovered during restoration, including swords, spearheads, metal tools, and everyday weapons, offering a glimpse into historical lifestyles.

In addition to the museum, new amenities were developed to enhance visitor engagement, including an amphitheater, a café, and walkways around the stepwell. These spaces are illuminated with strategically placed light fixtures along the walkways and stepwell walls, creating an inviting atmosphere.

Community involvement was a central aspect of the project, with educational workshops conducted to raise awareness about the stepwell’s cultural heritage and its role in water conservation.

Bansilalpet Stepwell, Hyderabad10

Bansilalpet Stepwell, Hyderabad10The overall restoration efforts stated in the various examples above resulted in public access over abandonment; and in the case of the Bansilalpet stepwell community, engagement was enhanced by at least developing further curiosity through the information display at art galleries and awareness through workshops. For the current social media generation and mindset, which needs a new spot to post about every week, they provided more instagrammable places to explore and photograph - a unique and modern expression of community engagement. Regardless, for a country dealing with poverty at large scale, these efforts of restoration for just beautification without purpose may after a point be rendered useless. The structures become just another standing monument, eating up a large portion of land, without serving any larger economical and social purpose, which was the original idea of having these stepwells.

It is also to be noted that very few of these restoration project reports are available to the general public for review and analysis. This lack of transparency prevents monitoring, comparing, reviewing and analyzing data, progress and results. A project report accessible to the public, especially for such novel projects, would help identify why certain ideas succeeded or failed, highlighting challenges to address and improving the current process.

Finally, the structural re-enlivening process should ideally go beyond restoration, conservation, and preservation also to revival; revival of function and rituals.

For example, the 900-year-old puṣkariṇī at Venugopalaswamy Temple at Manchirevula has been revived to serve for bathing and temple rituals. It is also observed that many such efforts made in villages for agricultural water sources, by the local population without the interference of any formal authorities, resulted in full fledged revival of these tanks; preservation, conservation and beautification automatically followed.

So this is how we can make the structures socially and economically viable again - by not only restoring them physically, but also by restoring their original purpose, both functional and cultural. This presents a challenge as modern-day views on bathing and water usage differ from the ancient and traditional usage patterns. The modern civic water supply system is in conjunction with the colonial idea of having a private space for all the daily rituals. Consequently, the design of city water supply systems are to enable the water directly into the taps at our homes. This water is generally sourced from a nearby river or lake, then first purified through an elaborate system at the city level; and finally distributed to area-wise Elevated Storage Reservoirs (ESR) which are connected to the underground water tanks of our buildings or individual homes. The water in them is further pumped to the overhead tanks of the buildings or independent houses which is connected to all the taps.

This means that there are 3 potential points in this whole process that can accommodate the use of stepwells. One is directly at the source, where these stepwells can become additional sources of collecting and storing rainwater; secondly, if covered and maintained they can replace the ESR by acting as storage units for area wise distribution; and lastly, building small scale stepwells for individual home usage and rainwater harvesting. This is an effective idea which is actually already in use; thereby considered a revival of technique. Using the stepwell at the first potential point, stage one - for collecting and storing rainwater - would also continually preserve the stepwell itself. This would, for example, address the sandstone chipping issue as in the case of Rani ki Vav. Large amounts of water can be continuously stored, serving the dual purpose of water supply for the locality as well as preservation of the stepwell itself, by strengthening the sandstone constantly with moisture.

To promote an eco-friendly and sustainable approach, a few more practices could be put in place. These, of course, require further discussion, deliberation, and tweaking based on the city, stepwell, and each use case; however, generally can be considered:

- The reconstruction process should prioritize the utilization of natural, particularly locally-sourced, materials.

- Additionally, planting tree species with water-retentive root systems around the well can enhance water conservation.

- Implementing specific policy measures can help restrict the use of incompatible modern techniques and materials.

- Practices such as installing electrical wiring, fixtures, drilling, or screwing into the walls of the wells should be avoided, as these actions can compromise structural integrity due to vibrational loads for which these walls were not originally designed.

- Furthermore, the use of electricity near stepwells may generate heat, contributing to potential damage. It is important to note that stepwells were traditionally not intended for use during non-daylight hours.

Culturally speaking, if we revive all the rituals, ceremonies and festivals around the stepwell by creating practice-based awareness formats, which is a step further to the educational workshops, we can foster camaraderie and community building - and thus the building of a true Indian civilization. For history is truly celebrated when we revive it and live it, not just by honouring it on gallery walls.

Conclusion

In June 2022, the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, announced a Jal Mandir Scheme for revival of Step Wells in Gujarat:

In view of their structural uniqueness as well as their role in water conservation, Government of Gujarat decided under mission mode, from 2007-08 to 2011-12, to revive, clean up and rejuvenate these stepwells, which are named as “Jal-Mandir” — Water Temple – as these are part of our national heritage. Nearly 1200 Jal- Mandirs were identified all over the State. Considering the importance of these heritage structures, the Government of Gujarat renovated several stepwells under Jal Mandir Yojana11.

The Ministry of Jal Shakti has taken up a nationwide campaign “Jal Shakti Abhiyan - Catch the Rain” (JSA:CTR) with the theme “Catch the Rain, Where it Falls, When it Falls” for creating appropriate rainwater harvesting structures in urban and rural areas of all the districts in the country, with people’s active participation, during the pre-monsoon and monsoon periods. Revival of traditional rainwater harvesting structures like stepwells has been envisaged as a critical part of this initiative.

The concept of Jal-Mandirs can be highly beneficial in regions with aridity, with a high groundwater table, and where assured water supply systems, such as tube wells or municipal supplies, are unavailable. Implementing this concept in such areas offers several advantages, and is particularly innovative as it promotes the sustainability of village water supply systems by fostering a sense of responsibility among the community. By integrating social and religious dimensions, it motivates people to maintain the system, thereby playing a crucial role in both water and heritage conservation.

Finally, future restoration efforts of not just stepwells, but any built heritage of India for that matter, should prioritize transparent documentation and public dissemination of project methodologies and outcomes. Laying certain policy groundwork through organizations like ASI to curb right practices, can aid in achieving this goal. Transparency, furthermore, would enable informed discourse, facilitate replication of successful models, and ensure collective ownership of the conservation process. By aligning traditional wisdom with contemporary needs, India’s stepwells can transcend their role as historical monuments to become active agents of water sustainability and cultural renaissance.

A journey not from neglect to nostalgia, but from neglect to nurture.

References

- Image Source - जानिए New 100 Rupee Currency Note में छपे Rani ki Vav की कुछ रोचक बाते

- What is the spiritual significance of water in Sanatan Dharma? – Sanatan Dharma

- Great Bath, Mohenjo-daro 20160806 JYN-03 - Great Bath - Wikipedia

- Pushkaranis | Sightseeing in Hampi | Hampi

- Abhaneri Chand Baori: India’s most photographed stepwell

- Agrasen Ki Baoli - Wikipedia

- Rani ki Vav - Wikipedia

- HERITAGE - Hyderabad Metropolitan Development Authority

- Mystery Water Level Rise at Delhi’s Agrasen ki Baoli Sparks Concern

- Saved in 500 Days, Stepwell With 22 Lakh Litres Capacity Was Full of Waste

- Stepwells of India