Indian Knowledge Systems Part 2

29 January, 2024

4595 words

share this article

The purpose of this series of three essays is to make the reader aware of the richness of Indian knowledge systems. It also focuses on the ontological and epistemological foundations of Indian knowledge systems. The series tries to give an overview of how Indian metaphysics differs from the scientific and modern perspectives of knowledge production and understanding of reality. Read Part 1 here.

The author does not make any claim of original scholarship in these areas. He is only trying to understand what the great scholars have already said. The essays draw heavily on the works of Śrī Chittaranjan Naik, Śrī Shatavadhani Ganesh, and Dr. SN Balagangadhara Rao. It is a paraphrasing and summarizing of their works, and hence there may be direct quoting without indication in each case. Every effort has been made to attribute the work correctly.

Ontology in Western and Indian Descriptions: Indirect Realism and Direct Realism

Ontology (‘onto’- real or existence; ‘logia– science) studies what is real and what exists. When it comes to perceiving objects in the external world, the standard Western paradigm is that light falls on an object first. This reflected light enters the eyes and falls on the retina, from where neural impulses travel via the nerves to a region of the brain. Here, the image gets a reconstruction, and the person ‘sees’ the object. The same sequence is true for all the other senses too, like hearing, touch, smell, and taste. This is the ‘stimulus-response theory of perception,’ a stimulus of some sort evoking a response inside our brains through an intermediate causal chain. Of course, there is difficulty in explaining how an internal image inside the brain projects to the outside world.

Hence, in effect, what we perceive in the external world is not as it really exists but how the interpretation occurs in our brains, which depends on our endowed senses. This is Representationalism - the perceived world as only an internal representation of an external world; hence, it is an indirect form of reality. What exists outside is never known.

What is known is the reconstruction of neural impulses in the brain. The world outside is not a true world in this sense. In Kantian philosophy, the original unknown is the ‘noumenon’ (in modern parlance, ‘the non-linguistic’ world), and the known constructed reality is the ‘phenomenon’. Representation is the contemporary scientific view that gets the term ‘Scientific Realism’ or ‘Indirect Realism’ and forms the basis of both philosophy and neuroscience.

In contrast, Indian philosophy for thousands of years has been clear on its stand on ’Natural Realism’ or ‘Direct Realism’. All six systems of Indian philosophy, with some minor variations, propound an active theory of perception where the perceiver is central in the scheme of things. The perceiver goes out and reaches the object in the world. This is the ‘contact-theory of perception’ of Indian philosophy in contrast to the ‘stimulus-response theory of perception’. Contact with the object by the perceiver gives direct information about the world as it exists. Hence, the external world, as seen or heard, is an actual world in its reality and not a construction.

This establishes the role of pratyakṣa, or direct perception, as a valid pramāṇa, or means of knowledge. This contrasts with Western philosophy, where the world can never be known; hence, perception is never a valid source of knowledge in western traditions. This is the driving conclusion of Śrī Chittaranjan Naik in his first classic book, Natural Realism and the Contact Theory of Perception.

Western Philosophy and The Problem Of Ontology

Ontological studies are divided into two groups: mind-independent and mind-dependent. One believes that material processes are real and that reality exists independently of the observer. In this position, the world exists independent of our perceptions of it. The other group believes that the immaterial mind and the generated consciousness are the true reality, and the world is dependent on the observer’s mind.

In the overwhelming contemporary position, which says that the world is mind-dependent, there are two further subgroups of explanations: a) Representationalism (Scientific Realism or Indirect Realism) believes that the perceived world is only an internal representation of an external world; hence, it is an indirect form of reality. The real world remains unknown. b) Idealism believes that the world we perceive is a construction. The world has no existence independent of the mind or our subjective perceptions of the world. Thus, in the “mind-dependent world” position, the mind either constructs an image of an existing outside world or the world itself with no outside world at all.

If there is a mind-dependent world, then what is the ontological status or the true reality of the world? All we ever know is the ‘phenomenon’, with the true ‘noumenon’ always unknown.

By the beginning of the 20th century, there was an impasse in the philosophical world, which was the ‘problem of the external world’: The perceived world appears to be external to us and to exist independently of our minds. Yet, what we perceive are secondary qualities, as presented to our sensory faculties and their specific powers. They are not the primary qualities that belong to the objects themselves. All Representationalist systems cannot thus effectively address the topic of ontology (reality), as the real world (noumenon) is always beyond our capacity of comprehension.

Even the intervening medium, such as space or air, through which data transmits from the object to the mind, would have existed prior to the appearance of the representations. In other words, they are noumena. In which case, how can we speak of the ideas of motion, medium, space, time, and their relations when they are all categories applicable to phenomena? The stimulus-response theory of perception presents a riddle. If we do not possess the capacity to speak of the real world external to us (or the noumenon) in meaningful terms, how would we indeed be able to investigate the topic of ontology? In the field of Western philosophy, this problem is unresolved to this day.

Consciousness in Indian Philosophies

Indian and western philosophies distinctly differ on many issues. Fundamentally, Consciousness (also known as the Self, Puruṣa, Cognizer) is primary in Indian traditions; it is secondary to matter in western traditions. Consciousness does not include a deep sleep state in western definitions. In Indian traditions, the three brain states are the awake state, the dream state, and the deep sleep state, and ‘Consciousness’ is transcendental to all three. Mind and matter are different from this Consciousness.

Indian philosophy makes a clear distinction between the Self and mind-matter as two distinct identities. Mind and matter belong to the same category. In Indian traditions, the category of the cognizer is the Self (or Puruṣa), whose characteristic feature is consciousness. Hence, Self, consciousness, cognizer, and Purusha belong to the same category of sentience. Mind-matter, also known as prakṛti and always insentient (inert or having jaḍatva), belongs to the distinct category of the cognized.

Mind and matter are the two modes in which objects of cognition appear, revealing legitimate objective reality.

In Indian tradition, the nature of an object never changes. When the circular shape of a coin changes to a square one, the law of identity (a thing as itself) stays constant, but it is “time” that presents the dynamism and change. Thus, Bhartṛhari’s Vākypadīyam says that the creative power of Reality is Time.

Unlike the western notions of an unknowable noumenon (original), where the perceived world loses its intrinsic character; in Indian philosophy, the term ‘unknowable object’ is devoid of reference (vikalpa), and is an illegitimate verbal construction (like the son of a barren woman). In Indian traditions, a conceived object cannot be unknowable, and if it is unknowable, there is no conceiving.

In this overarching principle, where the perceived world is independent of the mind, we return to the one world that we all experience and live in.

Indian Approach to Ontology: Contact Theory of Perception and Natural Realism

What is the ‘nature of the world’ as it appears through the theories of science? Śrī Chittaranjan Naik elaborates on the Indian idea of perception in his book Natural Realism and the Contact Theory of Perception. Firstly, there is no distinct thing in science called ‘the seer.’ Secondly, science postulates an elaborate mechanism from the object to the brain by which perceptions of objects occur.

As seen earlier, the very nature of this postulated mechanism makes the things seen in the nature of images, not the objects themselves. There are philosophers who stick to the representation of the world as images in the brain and yet hold that this is the true and actual world as it is. These are the Naïve Realists. And the philosophy that holds the perceived world to be the real world is ‘Naïve Realism.’

All traditional darśanas begin with an explanation of the pramāṇas. A pramāṇa is a means of obtaining knowledge about an object. The object known by means of a pramāṇa is called the prameya. Knowledge of the object is called prama. There are three basic pramāṇas (and three secondary ones which we shall see later) in traditional Indian philosophy. They are āgama (scripture), pratyakṣa (perception), and anumāna (inference).

Prama, or knowledge of an object, is not a distinct entity that stands between the subject and the object. It is a qualification of the subject, the knower. _Now, there is a distinct mark of the _prameya, or object, in traditional Indian philosophies that is missing in science and Western philosophy. This mark is the mark of ‘being seen’ or the mark of ‘knowableness’. This point is so vital that if we fail to recognise it, it is likely to lead us into such a position that we would not be speaking Indian philosophy at all, writes Śrī Chittaranjan Naik.

The mark of ‘being seen’ is a mark of prakṛti, or nature. In Pūrva Mīmāṃsā, Uttara Mīmāṃsā (Vedānta), Sāṅkhya, and Yoga, the prameya is seen _as distinct from the _seer. This feature of objects as being ‘the seen’ is held by Nyāya and Vaiśeṣika schools as well. In Navya-Nyāya, after defining the seven kinds of padārthas (word-objects) - substance, quality, action, universal, particular, inherence, and non-existence - it states that the common feature of all these seven categories is ‘knowableness’.

This feature of objects being ‘the seen’ finds expression in the philosophical tenet that there is a contact between the seer and the object when the object is seen. This contact is called sannikarṣaṇa, and the form that the (reflected) consciousness of the seer assumes in seeing the object is called ‘vṛtti.’ Thus, the entire world is “the seen”, and it is seen directly ‘as it is’ without there being any extraneous mediating factor between the seer and the seen.

So, according to traditional Indian philosophies, the object known is neither a mere presentation of something else that may be the real object (as in science) nor is it reducible to something lesser than what it presents itself as (such as a mere idea or artifact of the mind). An object is that which stands in front of Consciousness in the cognitive act of perception. The world of Indian philosophy is not the world of Naïve Realism, nor is it the ideated world of idealism.

If we must find a name for it, it may be called the world of Direct Realism – a world as it is that presents directly to Consciousness in an unchanged manner.

The Embodiments of The Self, Perception, Liberation, and Rebirth

The Self, being of the nature of consciousness, is self-effulgent. And it has, by virtue of its self-effulgence, the capacity to reveal objects directly and instantaneously. The absence of ubiquitous perception indicates that there is some primal covering over the Self, which obstructs its natural revealing power from revealing the objects of the world.

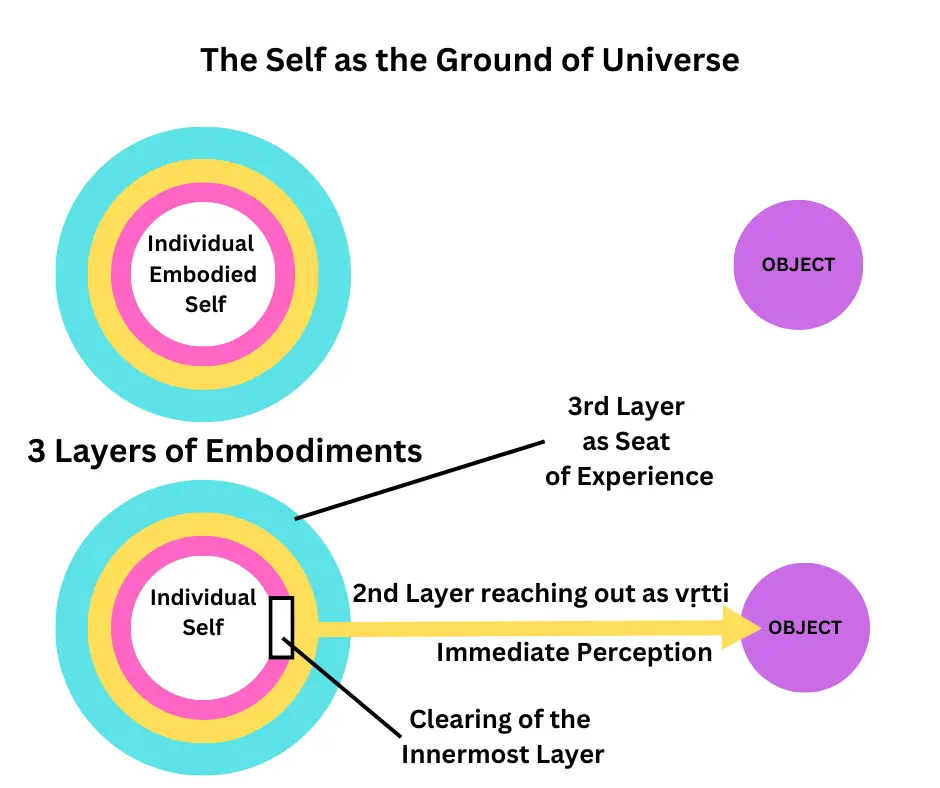

In Indian philosophy, this obstruction of the Self is the body itself. Embodiment is three-layered. At its most primal layer, the covering is essentially of the nature of sleep. The middle layer is the layer of ideation, the realm of mind. The outermost layer is the layer of the gross physical body through which the embodied self comes to be a creature in the world. The three layers are known as bodies with different names: mūla-śarīra (seed body), sūkṣma-śarīra (subtle body), and sthūla-śarīra (gross body), respectively.

The paradox of embodiment is that the embodiment of the self does not, in truth, exist. How can something arise in Consciousness - the ground of all the universe - and then contain it? The embodiment of the self comes about not through a spatiotemporal physical process, but through a cognitive condition whereby the Self becomes morphed into the body, as it were, and cognizes the body to be the self.

This erroneous idea is the mithya-jñāna superimposed on the Self and the body. This makes one see the body manifested in the realm of the world as the Self. An idea in the mind is the same as the body apprehended in the world as the Self. As seen before, the idea in the mind and its corresponding matter in the world are the same, appearing in two different modes of cognitive presentation.

The idea of the Self’s embodiment through a cognitive condition is central to Indian tradition; it forms a core tenet in all six darśanas, or systems of philosophy, though with slight technical variations. Embodiment is an erroneous cognitive condition; hence, right knowledge confers liberation. Embodiment persists so long as the erroneous knowledge continues.

Even when the physical body undergoes destruction, the notion of the body will continue to persist in the realm of the mind. The Self, still equipped with the power of thinking, would consider the destruction of the body a loss and crave to be in possession of a body. In the Indian tradition, this craving, along with the law of causation that bears upon the embodied jīvātma’s moral actions in its past births, results in the rebirth of the Self in another body.

It is within this three-fold structure of embodiment that we must look for the instruments of perception. For, even though the Self has the capacity to reveal objects by virtue of its intrinsic effulgence, maya obstructs its power of revealing. The innermost layer is the layer in which the clearing in the covering of maya appears; the middle layer is the layer that actively reaches out to the object with the help of the instruments of perception; and the outermost layer comprising the physical body is the layer that constitutes the seat of experience.

Seen and Unseen Causes, Karma, and Experiencing the World

Perception and experience of the world occur to the individual self when there is a clearing in the veil of maya. The clearing appears by the Wheel of Causation operating in nature, or prakṛti. The causality that operates in them is of two kinds: the seen and the unseen. The causality that operates between physical objects is of the seen kind. The nature of the objects themselves determines this.

The causality of the unseen kind is that in which the immediate effect of an action is invisible. But all actions of conscious agents do not produce unseen effects; it is only those actions that have a moral dimension to them that result in unseen effects. The effect of an individual’s moral action is apūrva, meaning that what did not exist before is newly born. It is the result of either a virtuous action or a morally transgressive action, and its effect surfaces at a future time when the conditions for it to fructify are satisfied.

The total of the unfructified apūrvas of an individual is the individual’s adṛṣṭa, also referred to as past karma since it is the net balance of the accumulated effects of past actions held in store for future fructification. Śrī Ādi Śaṅkarācārya, in commenting on the Bṛhadāraṅyaka Upaniṣad, in the context of a man’s rebirth, explains it as follows:

He has adopted the whole universe as his means to the realization of the results of his work; and he is going from one body to another to fulfill this object.

And as Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa says,

A man is born into the body that has been made ready for him.

There is perfect synchronicity between the world that an individual being perceives and the individual’s past karma. The Law of Causation (Dharma Cakra, or Wheel of Dharma) projects the manifested world in accordance with the collective past karmas of individual beings. An individual within this collective perceives that part of the manifested universe that his or her past karma entails him or her experiencing. The physical body is the seat of this experience, and the regulated uncovering of the veil of maya - the veil of sleep under which the individual being transmigrates - determines that part of the world the individual being will experience.

The Law of Causation does not violate the nature of objects. It is the nature of fire to burn and water to flow, and these natures are part of the law. The unfolding of the manifested world therefore does not violate the physical laws that operate between objects by virtue of their physical natures (dharmas). The causal force of Dharma Chakra acts as an unseen ordering force that determines the boundary conditions of the objects of the world. This is the overarching Law of Causation that the Indian tradition espouses, and it comes from śabda-pramāṇa, the means of knowledge by which reality beyond the realm of the senses may be known.

Advaita and Nyāya

There are philosophers who argue that there can be no means to know whether there are real objects in the world, given that everything we experience arises in our minds and is contained in the mind itself. This is a philosophical position termed “Idealism.” There are many variants of Idealism, from the kind first proposed in the West by Berkeley (1685–1753) to the later variants known as Phenomenology and Existentialism, but they all fit into the broad category called ‘Idealism’, as they hold the world to be born out of subjective ideations and belief systems. The terms ‘Naïve Realism’ and ‘Idealism’ are fine when used to refer to certain philosophies of the West. But Śrī Chittaranjan Naik writes that it is wrong to label Nyāya as a kind of ‘Naïve Realism’ or ‘Advaita’ as a kind of ‘Idealism’ - which many authors fail to realize.

Advaita is not Idealism because it negates both the mind and the world. And, at the same time, the mind and the world are different. Advaita does not negate only the world and leave aside the mind to say that the world is ‘mind.’ There are twenty-four tattvas defined in Vedānta, and only four of them are internal instruments (antah-karaṇas _comprising ahaṅkāra, citta, buddhi, and manaḥ),_ whereas the rest are external objects. The attributes of the internal instruments cannot transfer to the objects of the world. The world is not ‘mind’.

The objects of the mind, i.e., ideas and thought, have the characteristic of being determined by the individual’s will, whereas the objects of the world do not have the characteristic of being so determined. One cannot cook food by merely thinking about the food. In Advaita, the relations between words and objects are eternal, and each word denotes a specific kind of object with specific attributes. Without understanding this basic tenet of Advaita, it is wrong on the part of those authors to label Advaita as Idealism and thereby cause confusion.

Some use the oft-repeated criticism that Advaita’s position is that ‘nothing is real’ from a profound misunderstanding. The complete expression is brahma-satya, jagan-mithya. The subject matter of Advaita is Brahman and not the world, and thus, jagan-mithya is never an isolated proposition. The locution of jagan-mithya (world illusion) is always with the locution of Brahma-satya (Brahman Reality).

A discussion of the world, excluding Brahman, however, makes the world satya, or real. Denying the reality of the world, which excludes Brahman, reduces it to an unacceptable Nihilism. Hence Ādi Śaṅkarācārya takes the position that the world is real when refuting Vijñānavāda and other Idealist schools of Buddhism which deny Brahman. Modern proponents of Advaita Vedānta overlook this vital point.

Indeed, in both Advaita and Dvaita, the relation between Brahman and the world is the relation of Bimba-Pratibimba, the object and its reflection. There is a common misconception arising about the ontological (reality) status of the reflection seen in the mirror. The reflection of an object, say of a flower, seen in the mirror, is unreal because the reflected object is not a real flower. However, the object called ‘image of a flower’ is real because the reflection is truly an image of a flower. In other words, the object is not true to the name ‘flower’ but it is true to the name ‘image of a flower’.

In this world comprising various objects, all these objects may be the reflections (pratibimbas) of Brahman but they are true to the names they are known by. Hence, they are real. The world objects are all pratibimbas, having no existences by themselves but with their existences derived from, and entirely dependent on, the Bimba, which is Brahman, the Supreme and Sole Independent Existence. Without Brahman, the universe and its objects have no capacity to exist, just as in a mirror the reflections have no capacity to exist without there being objects.

Nyāya is not Naïve Realism. This is a caricature that has no bearing on Nyāya. The entire dichotomy between ‘images seen in perception’ and ‘unknowable objects out there in the world’ has been created by an incoherent hypothesis that perception takes place through the mediating mechanisms of the sensory network and the brain. The Nyāya (and Vedānta) theory of perception is based on the principle of contact between the subject and object, in which there is no chance of the reality of the world becoming ‘naïve.’ Nor is there in them a chance of the world becoming something other than what is seen. Therefore, the application of the term ‘Naïve Realism’ to Nyāya betrays a lack of knowledge of Nyāya.

The Perceptual Process in Indian Traditions

At the most primal level, perception is by the removal of the covering of maya over the individual self. In Advaita Vedānta, the covering of maya over the self is avidya or nescience. The removal of the nescience to allow the conscious light of the self to reveal external objects constitutes perception.

In the Indian tradition, perception is an active process in which the Self, as the Inner Controller, drives the senses towards their objects in accordance with the individual’s adrṣṭa.

On the removal of nescience, the self’s conscious light streams out to the object and envelopes it.

In this process, the mind assumes the form of the target object of cognition during a conceptual act. The form that the mind assumes in presenting an object to cognition is a vṛtti. The mind forms a vṛtti both when it constructs an object purely as a mental phenomenon as well as when it contacts an external object and envelopes it and assumes the form of the object. Perception is thus a composite process in which the self, the mind and the sense organs together participate to establish a contact with the object. The Nyāya text Tarka Saṅgrahaḥ explains it as follows: The self (ātman) contacts the mind (manas), the mind with the organ (indriya), and the organ with the object (viṣaya), and then perceptual knowledge takes place. This is a direct perception of the object and its quality too.

In Indian tradition, the attributes perceived of objects, such as color, taste are not subjective qualities but are objective qualities inherent in the objects themselves. This is in sharp contrast to the viewpoint of Contemporary Western tradition wherein they are subjective phenomenal qualities. In the Indian theory of perception, there is no transformation of the object in the process of presentation. Once the mind and sense organs contact the object and assume the form of the object by forming a vṛtti, there would be a conjunction of the mind, the sense organ, and the object at the very location of the object. There would be nothing in between the self and the object to hinder the conscious luminosity of the self from revealing the object in its true form.

The contingency of the mind and sense organs as distorting filters arise only when they have a defect hindering it from assuming the form of the object.

When such defects of the sense organs or the mind are absent, there would be nothing present in between the self and the object that can prevent the perception from revealing the object in a transparent and true manner. The perception of an object is in the actual spatial location where it exists and is instantaneous. There is no time-lag in perception. Śrī Chittaranjan Naik proposes an interesting experiment to prove this. One can refer to the wonderful book Natural Realism for further details.

In the case of touch, taste and smell, the (subtle) organs do not move out of the body, so the perception takes place at the location of the physical sense organs themselves when the objects come into contact with the physical sense organs of the gross body; whereas in the case of visual and auditory perceptions, the indriyas move out of the physical body to make contact with the object in external space.

While there are minor variations between the darśanas about the technicalities of perception, all the darśanas hold that perception takes place due to the contact of the (subtle) sense organs with the object. There is uniformity regarding perception being direct and revealing the object in its actual form through the contact of the consciousness with the object through the instrumentality of the sense organs and mind.

Such contact is instantaneous since the consciousness that appears within the body is the same Consciousness that exists without the limiting adjuncts of the body and which is in conjunction with all objects.

Hence, perception is nothing more than the removal of the covering of maya over the individual consciousness to reveal the conjunction that already exists with the object.

References And Further Readings

Gainsaying Ancient Indian Science in two parts by Michel Danino (https://pragyata.com/gainsaying-ancient-indian-science-part-1/)

Integrating India’s Heritage in Indian Education in two parts by Michel Danino ( https://pragyata.com/integrating-indias-heritage-in-indian-education-part-1/)

Indian Culture and India’s Future (2022) by Michel Danino

Indian Science And Technology In The Eighteen Century (2021) By Dharampal

https://pragyata.com/ananda-k-coomaraswamy-on-education-in-india/

Understanding Hinduism: V. Foundational Texts of Hinduism - Indic Today by Shatavadani Ganesh (co-authored by Hari Ravikumar)

https://incarnateword.in/sabcl/15/reason-and-religion The Collected Works of Sri Aurobindo

https://incarnateword.in/cwsa/20/the-renaissance-in-india-iv#p6 The Collected Works of Sri Aurobindo

https://incarnateword.in/sabcl/14/a-rationalistic-critic-on-indian-culture-ii The Collected Works of Sri Aurobindo

https://www.academia.edu/42795501/The_Brahmin_the_Aryan_and_the_Powers_of_the_Priestly_Class_Puzzles_in_the_Study_of_Indian_Religion by Jakob De Roover

Natural Realism and Contact Theory of Perception: Indian Philosophy’s Challenge to Contemporary Paradigms of Knowledge (2019) by Chittaranjan Naik

On the Existence of the Self: And the Dismantling of the Physical Causal Closure Argument (2021) by Chittaranjan Naik

https://pragyata.com/apaurusheyatva-of-the-vedas-part-1/ by Chittaranjan Naik

https://pragyata.com/apaurusheyatva-of-the-vedas-part-2/ by Chittaranjan Naik

Cultures Differ Differently: Selected Essays of S.N. Balagangadhara (2022) Edited by Jakob De Roover and Sarika Rao

https://pragyata.com/false-supremacy-of-science/ by Venkat Nagarajan

THE IMPERISHABLE SEED: How Hindu Mathematics Changed the World and Why this History was Erased (2023) by Bhaskar Kamble and edited by Sankrant Sanu.

INTRODUCTION TO INDIAN KNOWLEDGE SYSTEM: CONCEPTS AND APPLICATIONS (2022) by B. Mahadevan, Nagendra Pavana, Vinayak Rajat Bhat