A Fair and Gracious Dream, 2 - The শুদ্ধ Dream, Understanding the Old Elite

25 February, 2023

9921 words

share this article

An Old Dream

For a student of the history of Indian history, Arun Shourie’s biting masterpiece, Eminent Historians: Their Technology, Their Line, Their Fraud is a landmark work. Shourie, a forgotten old master of the Indic movement, is incisive, brutal and unyielding in his defenestration of the titular tricksters, ideologues and activists posing as historians. It makes for mandatory reading.

However, there was always one chapter in that book that stood out more than the others. And it is simply titled: “A circular”. When I first read this chapter, it acted as an important marker for me. It confirmed, in shockingly blunt terms, a suspicion that I always had when reading India’s official (i.e. Indian National Congress constructed) history: that something didn’t seem quite right in the things I was reading. There seemed to be a fog that was muddying the view. And it felt like a man-made fog, as if someone was putting their thumb down to prevent me from seeing the truth.

Of course, this is the infamous (শুদ্ধ-অশুদ্ধ) Shuddho-Aushuddho circular.

| Aushuddho | Shuddho |

|---|---|

| “Fourthly, using force to destroy Hindu temples was also an expression of aggression. Fifthly, forcibly marrying Hindu women and converting them to Islam before marriage was another way to propagate the fundamentalism of the ulema.” | Though the ‘ashuddho’ column reproduces the sentences only from “Fourthly…”, the Board directs that the entire matter from “Secondly… to ulema” be deleted. |

| “Sultan Mahmud used force for widespread murder, loot, destruction and conversion.” | “There was widespread loot and destruction by Mahmud.” That is, no reference to killing, no reference to forcible conversion. |

| “He looted valuables worth 2 crore dirham from the Somnath temple and used the Shivling as a step leading up to the masjid in Ghazni.” | Delete “and used the Shivling as a step leading up to the masjid in Ghazni”. |

| “Hindu-Muslim relations of the medieval ages constitute a very sensitive issue. The non-believers had to embrace Islam or death.” | All matters on this page to be deleted. |

| “According to Islam law non-Muslims have to choose between death and Islam. Only the Hanafis allow non-Muslims to pay jizya in exchange for their lives.” | Rewrite this as follows: “By paying jizya to Alauddin Khilji, Hindus could live normal lives.” |

| “Mahmud was a believer in the rule of Islam whose core was ‘Either Islam or death’.” | Delete |

To quote Shourie:

“The design is… to attribute evil to the religion of our country, Hinduism; it is to present Islam as the great progressive force which arose; it is to lament the fact that humanity did not heed the teachings of progressive men like Muhammad - till the “remarkable and comprehensive” Russian Revolution of 1917!”

The circular is tangible proof that we are not mad that when we read our allotted history, we feel like we are reading the history of a different country. And it is a brilliant, if not slightly terrifying insight into the minds of the political and intellectual elite that inherited rule of India from the British Crown, and a stunning formalization of the post-Partition communal ceasefire agreement that we know as Indian “secularism”.

And most importantly, for my series, A Fair and Gracious Dream, this circular and this concept of শুদ্ধ-অশুদ্ধ, is a great way to capture the final destination of the intellectual journey of the group of people that I like to call the “Legacy Elite”, or the “Old Elite”. And it is obviously a useful tool for us as we try and decipher the taste of the broth of Dreams that our Elite has prepared for our consumption. This is why I have decided to term the second part of this series, “The শুদ্ধ Dream” (The “Shuddho” Dream)

The genealogy of the idea

First, I would like to state that I will be focusing only on the journey of the Elite over the last 200 years. And even within them, I will concentrate on the intellectual elite, because all the other kinds of elites (economic, political, cultural, etc.) mostly get their sense of right and wrong, their Dreams, from the intellectual elite who pontificate over them. Therefore, it becomes important to ask the following of the Indian Legacy Elite:

What did they read throughout history?

What ideas did they come into contact with?

Were these ideas emergent (Indic) ideas, or foreign imports?

And finally, how did these Dreams lodge themselves into the mind of the entire elite?

These Dreams essentially function the same way as genetic code functions in the growth of a human being. When a human being is a zygote, all he or she “is”, is a singular cell with some genetic material in the form of proteins. However, these proteins (what we know as DNA) contain the “code” that governs the trajectory of the future growth of that individual, with help from their environment. If we were to use a metaphor, the DNA protein is pure potential energy. It contains the vision of what that singular cell could grow into, if provided the right circumstances.

In my opinion, the Dreams that possess any society’s intellectual elite perform the same function. And this is why it is important for us to focus on them. This is not to say that what the common person or the collective Demos thinks doesn’t matter, or should not be studied. But this will not be an article that focuses on that.

So, now that the terms of our questions are settled, the next step is: where exactly do we start?

Here are a few questions that need answers:

How does the Bengali Hindu elite go from the Dharmic nationalism of Bande Mataram, to nearly a century’s obsession with communism?

How does The Hindu go from a foremost nationalist newspaper under the stalwart patriot G. Subramaniya Iyer, to publishing full-page adverts for the Chinese Communist Party, multiple times a year?

How does cutting-edge Indian commentary make the trip from the fiery nationalist newspapers and magazines like The Mahratta and Bande Mataram, to the Coconut online outlet The Juggernaut, which is nothing but white progressive wine in a “South Asian” bottle?

The answer to these questions lies in a dialectical journey - the meandering intellectual journey of this Inherited Indian elite.

They are, in many ways, an unremarkable bunch. With some notable exceptions (Rabindranath Thakur, Aurobindo Ghosh, etc.), they have been shallow followers of international trends, and don’t really have many ideas or works that say something new to the rest of the world. If one looks at the grand corpus of their works, there are only a few of them that can be considered works of international repute. Their record has been one of mimicry, a mimicry of elites of other nations who represent greater competence and vitality. To quote V.S. Naipaul from his book An Area of Darkness:

…no people, by their varied physical endowments, are as capable of mimicry as the Indians.

Despite this, they have maintained a degree of importance in the minds of the global elite, because they have owned and “represented” India, one of the largest masses of people in the world. They have lived off this ability to “represent” India, and used the power that comes with this to impose their will on the institutions of this country. The higher you climb on the Indian economic ladder, the more of them you’ll find, along with their naïve and nonsensical outlook of the world, which usually comes fused with an extreme sense of moral self-righteousness. They are a curious bunch, but that only makes them more worth studying.

But where to start?

It is the special mimicry of an old country which has been without a native aristocracy for a thousand years and has learned to make room for outsiders, but only at the top. The mimicry changes, the inner world remains constant: this is the secret of survival. Yesterday the mimicry was Mogul, tomorrow it might be Russian or American, today it is English.

- An Area of Darkness

Hindu elites existed in the medieval wastes of the Indian Subcontinent, both in the north and south of the country, but their influence was scattered and uneven. Some northern elites (mostly Rajputs) found themselves in the Court of the Mogul himself, serving important positions and bringing about reforms like those under Akbar, but most remained petty zamindars and local “rajas”, a subdued bunch surviving on past glories. In the south, the Hindu elites had a much smaller period of servitude than their northern counterparts. The Chola Empire, the Vijayanagara Empire (and its various successors like the Wodeyars and the Nayakas) made sure that southern Hindu elites were more powerful, and consequently were more productive in their cultural and literary output. But across the nation, a similar pattern had emerged: the power and influence of the Hindu elite was either eroding, or was being preserved at the cost of much blood and resources.

However, I think that for the purpose of this article, it is best to start after the arrival of the British, and especially after the implementation of their English education policy in India. This is because our entrenched Legacy Elite traces its origins directly to the arrival of the British and the “shock-therapy” of modernity. It is the first stop on this rather tumultuous but consequential journey. We start, therefore, with the various manifestations of the British Liberal Dream.

Ingredient #1: First contact with the Anglos

As the British fortified their hold over Bengal in the late 1700s, their Home Country was at the crest of a wave of economic and intellectual changes that would transform the Old World, and create the one we inhabit today, not just in the U.K., but across the globe.

Coming off the winds of the Renaissance of art, literature and culture that woke up the European continent, the Anglos added their own ingredients to the continental cake, pioneering the development of concepts like human rights, reason, scientific inquiry, English Common Law, and political liberalism. Thinkers like John Locke, Thomas Hobbes, the American Founding Fathers, and later, John Stuart Mill, were the intellectual thrust of the spirit of this small island-nation, a spirit that would go on to establish a thalassocracy that in many ways, continues to govern the world even today.

The proof of their victory is that their ideas are so ingrained into every one of our minds, that we don’t even consider them to be political ideas anymore. Who today, for example, would even consider speaking up against the rule of law or Human Rights? How many mainstream political parties in modern democracies would explicitly oppose an individual’s right to free speech? Whether you like them or not, the ideas of these thinkers are the starting assumptions of the polity of most of the world, including our own. It is quite a legacy to have left behind.

As Indians, we obviously had a special and involuntary association with these people for nearly two hundred years. And their impact here is consequently clearer than in other parts of the world. It is explicitly visible in most Indian institutions, and implicitly visible in so many ways that they would be impossible to list out completely. You see The Ghost of the Empire past every time you visit an old High Court, and do your best to mimic 19th century British competence inside the Court halls. You see it in the “civil lines” and “cantonments” that populate every major Indian city. You see it in the fact that I am writing this article, and you are reading it, in their language. In this, and so many other ways, we Indians are still living within the confines of the structures that the Anglos erected around us.

And it is my belief that any true attempt at understanding the Legacy Indian elite has to first realize how deeply the various fragments of the British Liberal Dream have been internalized by them. The Indian elite has possessed these ideas, and has made them their own. It is their only working definition of what competence looks like.

So let us start with the first manifestation of this Liberal Dream. It is a Dream that would have represented a world of opportunity to the demoralized Hindu elite of the 18th-19th century, and perhaps unsurprisingly, is also the most extreme one possible: The Derozians andYoung Bengal.

The Derozians, through their outlandishness and rebellion, represented exactly what you would expect when an elite overseeing a stagnant civilization, that has so deeply internalized “learned-helplessness” that it cannot imagine anything else, encounters the works of Jeremy Bentham, Adam Smith and David Ricardo. It is like a child raised in a conservative family rebelling when he flies the nest for the first time. The Derozians, named after the firebrand professor Henry Vivian Derozio at Hindu College in Calcutta, wanted a complete break with everything that made them “Indian”, “Hindu” and “Bengali”. They denied the sacredness of the Ganga river, converted to Christianity, and pioneered the Bengali language novel. They did these things because the people who had conquered them - British Aristocrats - also did these things. In many ways, the Derozians represent the purest attempt at mimicking the Liberal Dream in India. In the beautiful words of the Oriental Magazine critic:

The Derozians made “progress” by actually cutting their way through ham and beef and wading to liberalism through tumblers of beer…

It is important to study the Derozians because their archetype - the complete rebel - still persists today in sections of the Legacy Elite. This Dream of wanting to fully disinherit the fruits of this civilization lingers, even if it remains on the fringes. It rears its ugly head just enough that we should take it seriously.

The Liberal Dream obviously did not stop with the dizziness of the Derozians. It mutated and matured in its long two-hundred-year journey. But the impact of this first iteration remains undeniable. In fact, it was the Indian National Congress stalwart Surendranath Banerjee who described the Derozians as the “pioneers of the modern civilization of Bengal, the conscript fathers of our race whose virtues will excite veneration and whose failings will be treated with the gentlest consideration”.

When one reads such lines, the ideological inheritance of the Dream becomes completely clear. It is therefore important for the Dharmic movement to understand the Derozian Dream, especially as I expect we will see it more often, as the combined assault of modernity and globalized liberal culture accelerates the “shattering of the old Hindu equilibrium” (a Naipaul concept from his second India book, A Wounded Civilization).

After the Derozian Dream decayed, the baton of the Liberal Dream was picked up by the Brahmo Samaj, led by an East India Company employee named Ram Mohan Roy. If I have to summarize the instincts of the “Brahmo Dream” (especially in its heyday under Roy), I would say that they strived to create an Indian society that valued both western liberalism, as well as the indigenous identity of Dharmic society. But, if forced to choose between the two, the Brahmos would have come down squarely on the side of western liberalism.

This is clearly demonstrated in Roy and the Brahmos pushing for the “reform” of Hindu society using the blunt force of British State power. This was opposed even at the time by Sir Radhakanta Deb and the Dharma Sabha, and the coalition known as the Bharat Dharma Mahamandal. I point this out because it is important to remember that even during the zenith of the Brahmo Dream’s influence, it still faced significant, and credible pushback within Hindu society, to preserve the society’s sovereignty over its own affairs.

And the nature of this opposition to the Brahmo Dream is important for us to understand. Radhakanta Deb did not oppose the abolition of Sati because he supported it morally. He opposed the British State interfering in the personal matters of Hindus on the grounds that it pruned away at Hindu agency over their own matters. It was primarily an opposition to method, not to substance or principle. This reasoning shows up again a few decades later in Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s opposition to the British State raising the minimum age of marriage for Hindus. To quote the great man himself:

We would not like that the government should have anything to do with regulating our social customs or ways of living, even supposing that the act of government will be a very beneficial and suitable measure.

Despite this opposition at the time, the Brahmo Dream still matters, because it was the first sign of this Anglicized Indian elite being willing to break family silver to the point that it can never be glued back together (like the Japanese artform of Kintsugi). They crossed many red-lines of Hindu society and collaborated with the British and Christian missionaries to achieve many of their reforms. In doing so, they set a train in motion that would one day bring us to the destination of the Hindu Marriage laws enacted by the Indian State after Independence, making Hindu personal laws subservient to the whims of the State.

Today, it is important for us to understand that there is a direct line between the reformist impulses of the Brahmo Dream, and the current Legacy Indian elite’s eagerness to work with foreign media outlets to criticize who they perceive as their domestic enemies. This instinct sees the West as the “elders in the room”, whose voice counts for more than an Indian’s in the matter of governing Indians, and it is not too different from a younger sibling going to complain to the parents in the case of an intra-sibling skirmish. We should not be surprised to see Ramachandra Guha talking down to us from the bully-pulpit of Foreign Policy ever again.

The Brahmo Dream also shows us the first signs of this Indian elite developing a strategic patience. In their reformist revolutions, the Brahmos gave up the adolescent tantrums of the Derozians, and understood the value of working slowly, but persistently, to accomplish their desired goals, even if they took longer to achieve. They understood that the revolution does not need to arrive today, and that instant gratification is the mark of an undeveloped brain. And this strategic patience of the Brahmo Dream is yet another quality we see today in the Legacy Indian elite. Having been in political wilderness for almost a decade, they are patiently biding their time, finding cushy landing spots in western institutions and media houses, waiting for the time when their preferred dispensation returns to political power.

And lastly, it is crucial to remember that the Brahmo Dream was not a phenomenon restricted to the elites of Bengal. In fact, its nationwide presence is something that is rarely discussed and understood. As British control spread to other parts of India, and the tides of an English education arrived to the shores of Pune, Lahore, and Madras, we see the development of a similar elite in the rest of India. In Bombay Presidency, we see the emergence of the Prarthana Samaj (founded by Atmaram Pandurang with the direct help of the erratic Keshub Chandra Sen) and the Paramhans Mandali; in the Panjab, we see the emergence of the Deva Samaj under the leadership of Shiv Narayan Agnihotri; in Madras we see the formation of the Veda Samaj (founded by K. Sridharalu Naidu with, again, the direct assistance of K.C. Sen). The Brahmo Dream was not just a “Bengali” Dream.

Of course, as the years went on, the Brahmo Dream and the Brahmo Samaj itself fractured, most directly due to the bizarre behavior of K.C. Sen. But the foundations of the Dream of the current Legacy Indian elite still rest strongly on the shoulders of the Brahmo Dream. In fact, this entire cabal of lawyers, activists and professors also created and populated the early years of another organization that we are all very familiar with: the A.O. Hume-founded Indian National Congress. In many ways, the Congress was the next step - the inevitable politicization - of the Brahmo Dream, as it worked to find Indians a more prominent place within the British Empire.

I hope that I have demonstrated, through this brief journey through time, just how significant and influential this Brahmo Dream was, and remains. In many ways, it is the source of so many of the current Legacy Indian elite’s axioms: a State that considers it its duty to “reform” Hinduism (but keeps a principled distance from minorities), a State that puts western liberalism and “progress” above the indigenous idea of India. When one looks with a pensive eye, one finds that the Brahmo Dream is still alive and among us.

But of course, this isn’t the end of the journey. The Brahmo Dream, though revolutionary in its time, would grow in many different directions, and would gather even more influences from foreign ideas as the decades went on.

Ingredient #2: A forgotten work, and a Wolf in Sheep’s clothing

By the late 1800s, the Brahmo Dream had been internalized by the second-generation of the emerging anglicized Indian elite. But as often happens, these ideas were now considered too boring, too lacking in energy and in radical possibility. They became the ideas of the grumpy old men who pounded the desks at INC sessions and sang sincerely for the long life of the King of England. They were old news.

The time had come for a new generation of the Indian elite - in many cases the literal children of the Brahmo generation - to dream a new Dream that would inspire them, and become the animating spirit of their desires to reshape the country.

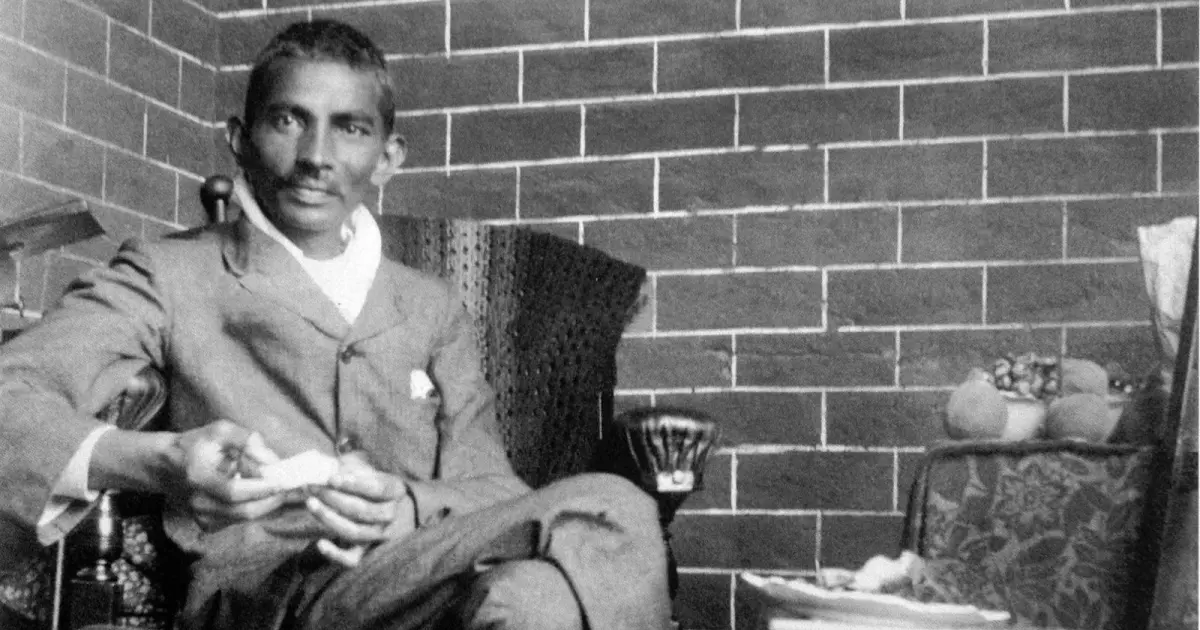

These are also individuals who should be very well known to us. Most of them were people who fought for Indian independence, and eventually, somehow, achieved it in 1947, along with the bloody nose of Partition. Yet, many of these figures - M.K. Gandhi, J.L. Nehru, Lala Lajpat Rai, Subhas Chandra Bose, etc. - are known so poorly to us. We do not study them as historical figures. We do not give them the privilege of being understood based on their own writings and words. We do not appreciate the Dreams they dreamed. Instead, we have mythologized them to the point of being unrecognizable. Perhaps, it is now time to look beyond this “child’s version of history”, and to give these figures the serious study they deserve.

The first thing we need to understand is that this particular crop of elites was guided by the need for radical action. They were raised in the mollifying miasma of the “prayers and petitions” of the Moderates (or as Sanjeev Sanyal calls them, Loyalists) of the Indian National Congress, while also coming into contact with an elaborate thaali of radical ideas from across the world. There are honestly too many of these ideas to list out, and these ideas were not restricted to Britain either. Russian, Japanese, Irish, and the late 19th-century German ideas entered their mental diet in this period. But given that we want to use them to understand the current Legacy Elite, it only makes sense to focus on the two most significant people of this generation: M.K. Gandhi and J.L. Nehru.

Mohandas Gandhi, born in the Princely State of Junagadh, famously traveled to London in his quest to become a Barrister of Law. In the U.K., he developed a particular fascination for western and Christian thought, as well other, more peculiar obsessions like an exploration of “ritual and body purity”. Naipaul, again in An Area of Darkness, makes the following claim about Gandhi:

“He saw India so clearly because he was in part a colonial. He settled finally in India when he was forty-six, after spending twenty years in South Africa. There he had seen an Indian community removed from the setting of India; contrast made for clarity, criticism and discrimination of self-analysis. He emerged as a colonial blend of East and West, Hindu and Christian.”

“Gandhi never loses the critical, comparing South African eye; he never rhapsodizes, except in the vague Indian way, about the glories of ancient India.”

This is an assessment I largely agree with, and if you read Gandhi, he does too!

In his own words, the two books that influenced him the most were: The Kingdom of God is Within You by Leo Tolstoy, and Unto this Last by John Ruskin. He even named his farm in South Africa “Tolstoy Farm”. If we add a dollop of Russian Orthodoxy to a cake of Jain philosophy, and a lasting love for the father of Fabianism, we get the mercurial mind of Mohandas Gandhi, who is perhaps best described by the oxymoronic expression “Russian Orthodox Hindu”.

As we can see, this man has almost no resemblance with the mythologized figure we know as “Mahatma Gandhi”. The latter is a manufactured symbol of the Legacy Elite, a foundational figure of the Dream of what they call “The Idea of India”, a term which has been borrowed lazily from the American political discourse, and has no real meaning in the history of a civilization that is at least four-thousand-years old; just like its sibling, the “Founding Fathers of India”. (This tweet sums up my feelings on this latter abomination quite well).

While we might think that Tolstoy was the main influence on Gandhi, I believe that it is the other person - John Ruskin - who is the actual protagonist of this tangled tale. In no uncertain terms, I consider Ruskin’s impulse in his previously-mentioned essay, his Dream, to be a fundamental axiom of the world’s politics of the last hundred years. His impulse is so ingrained in our minds today, that we do not even consider it to be political - the ultimate victory for any ideology. Even if you have never read the essay, dear reader, you know its message on a very deep level.

John Ruskin was, in a true sense of the word, a Renaissance Man and a typical Victorian busybody. There are very few people whose Wikipedia page has a section called “Legacy”, and contains the sub-headings “art, architecture, and literature”, “craft and conservation”, “society, education and sport”, and “politics and critique of the political economy”. He was the archetypical 19th century British polymath.

Even among this catholicism, his standout work is the previously-mentioned Unto This Last, a chronicled essay that Gandhi himself says “cast a magic spell on him”.

The title of this enchanting essay was derived from the Gospel of Matthew in the New Testament. It was a commentary and criticism of the dominant strain of economic thought governing Britain in the 18th and 19th centuries - Laissez Faire, mercantilism and free markets. The essay looks at the “eleventh hour workers” in the Christian story, but instead of finding the intended religious message, turns it into a discussion on how a society should distribute its resources more fairly. These workers in the Christian story had been hired only for the last few minutes of the day, but had been paid the entire day’s wages, and Ruskin used this fable to hammer home his critique (The message of the essay reminded me of another famous poem that tackles a similar theme: Bertolt Brecht’s A Worker Reads History).

This essay is, without exaggeration, one of the most influential pieces of writing in the last two hundred years. It laid down the foundations of what we know today as “social democracy”, that is, a democratic setup where the State functions as a welfare state that provides for the well-being of its citizens or subjects. The work, written in 1860, would go on to inspire an entire generation of critics of the old economic consensus in Britain (something that Scottish thinker Thomas Carlyle called The Dismal Science) and would eventually lead to the birth of the Labour Party in Britain in the year 1900.

It is the most dominant economic idea that has emerged from a country which another famous man once described as “a nation of shopkeepers”. It was the seed that grew into the idea that became the foundational ideal of the New Deal in the United States, a key moral impulse behind the United Nations, and yes, even a core idea behind the post-Independence Indian State. I have always thought that this idea of Ruskin is best captured by the word “progress”: a very modern idea that claims that political, economic and social circumstances have, and will, always get better with time (also called Whig History). Have you, dear reader, ever met anyone who is against “progress”?

Ruskin’s Unto This Last is a crucial landmark in the Indian context too, because it was the inspiration of Gandhi’s coinage of the expression Sarvodaya, which means “universal uplift” or “progress of all”. Sarvodaya was the actual title of Gandhi’s translation of Unto This Last into Gujarati, and served as the animating Dream of many Gandhians like Vinoba Bhave. To the extent that there is any concrete idea in the messy and vague world of “Gandhianism”, Sarvodaya it is**. Even the BJP’s economic policy of Antyodaya, developed by Pandit Deen Dayal Upadhyay, is nothing but a philosophical extension of this very idea. One can see the eleventh hour workers jump out of the page as one reads about the “upliftment of the last man”…

Through a series of bizarre events, this little essay from England has become the dominant Dream of not only the Indian elite, but the animating impulse of almost the entire western elite when it comes to ideas of social justice and equality. It is a Dream that the world’s elite has now been dreaming, with brief flirtations with the Red Dream, for nearly a hundred years. Every discussion on economic policy takes place with the impulse of this Dream as the central node. Talk about leaving a legacy!

(It does make one wonder: what other idea exists today that is currently seen as too small or radical, but will one-day blossom into a tree like this?)

But Ruskin’s contributions to the Dreams of the Indian elite don’t end with the spell he cast over Gandhi. Other British thinkers who were inspired by Ruskin’s writings have also shaped the Dreams of the Legacy Indian elite. In this context, we must discuss J.L. Nehru, and the Fabians.

The Fabian Society was to Ruskin, what Nehru is to Gandhi: a spiritual, but not literal heir to the throne. If Ruskin’s essays were mere criticisms of the then-dominant Dismal-Science Dream in Britain, then the Fabians, led by various Victorian “visionary” elites like Edward Carpenter, John Davidson, Havelock Ellis, and Edward R. Pease, turned this criticism into a formula for political organization. If there’s one thing that we should associate the Fabians with, it is the concept of Democratic Socialism. This is an ideology that advocates for the achievement of socialist ends through slow, creeping, democratic means (does it remind you of something?). And perhaps even more so than their Dreams, we find in the Fabians another explanation for the strategic patience of the Indian elite.

After all, the Fabian Society gets its name from the Roman general Quintus Fabius Maximus Verrucosus (whose nickname was Cunctator, meaning the “Delayer”). To quote the world’s encyclopedia:

His Fabian strategy sought gradual victory against the superior Carthaginian army under the renowned general Hannibal through persistence, harassment, and wearing the enemy down by attrition rather than pitched, climactic battles.

The first pamphlet published by the Fabian Society contained the following note:

For the right moment you must wait, as Fabius did most patiently when warring against Hannibal, though many censured his delays; but when the time comes you must strike hard, as Fabius did, or your waiting will be in vain, and fruitless.

Their coat in arms was a literal wolf in sheep’s clothing! They were not trying to be subtle!

And in the case of the Fabians and our beloved first Prime Minister, the links could not be any more glaring. His methods and ideology map on perfectly with “socialism through democratic means”, and his actions bear fruit to the ideology. To quote William Huse Dunham Jr.:

It was at this time (between the two World Wars) that many of the future leaders of the Third World were exposed to Fabian thought, most notably India’s Jawaharlal Nehru, who subsequently framed economic policy for India on Fabian socialism lines. After independence from Britain, Nehru’s Fabian ideas committed India to an economy in which the state owned, operated and controlled means of production, in particular key heavy industrial sectors such as steel, telecommunications, transportation, electricity generation, mining and real estate development. Private activity, property rights and entrepreneurship were discouraged or regulated through permits, nationalization of economic activity and high taxes were encouraged, rationing, control of individual choices and Mahalanobis model** considered by Nehru as a means to implement the Fabian Society version of socialism. In addition to Nehru, several pre-independence leaders in colonial India such as Annie Besant - Nehru’s mentor and later a president of Indian National Congress – were members of the Fabian Society**.

While Nehru’s fascination for pure Marxism and “scientific socialism” often makes us think of a certain bearded German, the more accurate categorization of his Dream is Fabianism.

And so it is that a Dream shown by a four-part essay written on the eleventh-hour worker, somehow decided the direction India would take after Independence. Dreams are powerful things…

And I don’t think I need to explain how influential this Dream is among the Indian elite. It is the software that our elite has been running since at least 1947. Every single humanities professor in Delhi, every bureaucrat walking the hallways of a dingy office in Lutyen’s city, every Judge, and even most politicians, inhabit and work, unflinchingly and subconsciously, towards the fulfillment of the Fabian Dream.

Pure Communism also became the Dream of some parts of the Indian elite, most notably in West Bengal and Kerala, but in my opinion the only real difference between the Fabian Dream and the Red Dream is that the former wants to reach the destination in fifty years, while the latter wants to reach the same destination today. It is a case of the narcissism of small differences.

These two Dreams - the Brahmo and the Fabian - give us two very significant stops in the journey of our Legacy Elite. Even today, they pervade every aspect of elite political discourse. These Dreams are the waters that even dissidents and political opponents must swim in. They are sticky, and lindy Dreams. But while they have dominated the political and economic goals of the Legacy Indian elite, the Partition of the country on religious lines in 1947 necessitated that some additional ingredients be added to the broth of the Brahmo and Fabian Dream. And this ingredient is what I call Shuddho (শুদ্ধ).

Ingredient #3: শুদ্ধ

At the stroke of midnight hour, the Fabian Dream found itself in-charge of a neutered nation. Its aspirations for the eleventh hour worker were suddenly subjected to the annoying distraction of the forced displacement of millions of people within their own nation. The reality check of Partition finally forced the Fabian elite to pay attention to a group of people they had been condescending and ignoring for decades: the old Muslim elite of India.

Did the Fabian elites really think that an organized minority with a memory of “ownership” over Hindustan that lasted centuries, would not want a share of the country? That they wouldn’t have ambitions of shaping the Subcontinent’s future according to their will? That Khilafat wouldn’t evolve into Partition? As we all know, this other Elite had Dreams of their own. And it could only have been enabled by a willing victim: a Fabian elite who refused to - did not want to - see the truth for what it was. Of course, we unfortunately know this tragic tale ends. The fruit of the Fabian faux-pas was a searing line drawn at the two limbs of the nation. Naipaul famously said in his book A Bend in the River:

“The world is what it is; men who are nothing, who allow themselves to become nothing, have no place in it.”

Unfortunately for us, this Fabian Elite did have a place in India: at the very top.

We must understand, however, that the reality of Partition did spring the minds of our Fabian elite into action. We might think of their behavior in this period in terms of cowardly inaction, but they were acting. Just not in the way that was required. They “accepted the reality” of the violent vivisection of the nation, but also thought of it as an important event that needed to be dealt with in a very particular manner. This approach to the fallout of Partition created the third ingredient of the broth that is the current Dream of the Legacy Indian elite: শুদ্ধ (Shuddho).

The delicious irony, of course, is that this discussion about about the শুদ্ধ Dream cannot be had without us getting very, very অশুদ্ধ (Aushuddho).

The first thing we observe as we wade into the শুদ্ধ Swamp, is that the primary goal of the শুদ্ধ Dream, even while the Panjab and Bengal were still bleeding, was to “ensure the safety” of the Muslims who chose to remain in India after Partition. In the শুদ্ধ mind, a hard line needed to be drawn in the sand after August 15, and everyone was to start at ground zero. Despite the nature of the facts at hand, শুদ্ধ decreed that Indian Muslims, even their elites, were not to be blamed for Partition in any way or form. And to accomplish this, the শুদ্ধ Dream felt that it had to fight every actual, as well as perceived, criticism of Islam in the Indian Subcontinent. This is not too different from the behavior of a parent trying to fight back criticism of a spoiled child. And this sense of “parental responsibility” is a good way of understanding the শুদ্ধ urge to bury their heads, and to force us to bury our heads, deep into the sands of the Thar desert. The শুদ্ধ mind also naturally thinks it is doing this for a good cause: the “Communal Harmony” of the nation. They are definitely the heroes of their own story. They are the good people fighting against hatred. This is the noble lie of the Legacy Elite, a sense of enforced-harmony that must be maintained at any cost. Any cognitive dissonance and contradictions produced by the execution of the শুদ্ধ Dream are simply ignored.

It has therefore necessitated that every piece of cultural and historical memory be put through what I call the শুদ্ধ shredder. অশুদ্ধ (Aushuddho) goes into this magical machine, and শুদ্ধ (Shuddho) comes out on the other side, ready for us all to repeat, just like we repeat our puja prayers. Sometimes the shredder is formalized, like Shourie’s circular, but it more often acts on instinct. The শুদ্ধ Dream also has very particular requirements from a Dharmic person: their duty is to become a “secular person”, adopting an adjective that has historically only been used to describe States, not persons! The শুদ্ধ Hindu must always be repentant, and be constantly on-guard against the ever-advancing forces of “majoritarianism”. It is a state of constant praxis, and it is no wonder that it is attractive today to the younger elements of the Legacy Elite.

So the current শুদ্ধ equilibrium was conclusively established: a ceasefire agreement created to enforce the Commandment of Communal Harmony. Over time, however, this practical ceasefire agreement has evolved into a self-fulfilling mythos and ideology. This is what we know as “Indian secularism”: a post-hoc rationalization and idealization of a pragmatic ceasefire. This is the anatomy of the শুদ্ধ Dream, a deep moral impulse felt by our current Legacy Elite.

And this শুদ্ধ self-righteousness also means that they reject any efforts to make them see the truth for what it actually is. They obfuscate, deflect, pathologize, label, emotionally manipulate, but stubbornly refuse to accept the factual reality and causes of Partition. In the words of C.S. Lewis:

“Of all tyrannies, a tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive. It would be better to live under robber barons than under omnipotent moral busybodies. The robber baron’s cruelty may sometimes sleep, his cupidity may at some point be satiated; but those who torment us for our own good will torment us without end for they do so with the approval of their own conscience.”

We all know what this tyranny, this শুদ্ধ Sophistry, looks like:

“Why are you digging up the past?”

“We need to look forward, not backwards”

“The British and Savarkar actually caused the Partition”

“If we accept that Islam caused the Partition, we would be no different from the Pakistanis”

We have all rolled our eyes while trying to reason with these শুদ্ধ prayers.

But there is another layer to this manufactured myth, one that I call “শুদ্ধ cynicism”. Because the reality is, if you actually talk to someone drenched in the শুদ্ধ Dream, and refuse to get carried away by the pathos (emotional appeal) of their arguments, you start peeling away the idealistic layers of the onion, slowly but steadily. And the bulbous portion of the শুদ্ধ Dream that remains is one of harsh pragmatism and cynicism. Once poked in the axioms, the replies suddenly change to:

“There is no other way to keep the peace in this country”

“There would be riots if we did not do this!”

“Do you know what would happen if we taught history honestly?!”

And suddenly, as the non-sequiturs, ad-hominems and insults are brought out, the শুদ্ধ Hindu in front of you gets replaced by a pale imitation of the British colonial historian’s view of India: if the British State and ruling class did not exist, these animalistic Indians would be at each other’s throats and devour each other. The internalization of the British Aristocrat’s Hegelian analysis of India is complete. The শুদ্ধ Dream makes just one modification to this: it replaces the British State with the শুদ্ধ equilibrium. (Ohh, and naturally, Indian civilization is not worth saving in the first place, because of Caste! and Sati!)

Only when one sees the cynical core of the শুদ্ধ Dream, can they understand it for what it is: a Tired Dream of a Tired Elite. A faulty dam built to stop an onrushing river. From the day of Partition, this শুদ্ধ Dream has been a death-row convict waiting for the day of his execution.

But despite these contradictions, the শুদ্ধ Dream successfully ossified itself in the institutions, and in an age without social media, also in the minds of a few generations of the Indian people. Perhaps it was due to the fact that the only other viable Dream in the 1950s-90s period was the Red Dream. To many, this haunting specter of a Red Takeover made the শুদ্ধ Dream look moderate in comparison. A great example of this is the criticism of Nehru by Leftist British historian Perry Anderson: “Where the Hindu majority ends, AFSPA begins”

If the only other viable alternative was calling Nehru a proto-Hindutva figure, would you not find the শুদ্ধ Dream comfortingly moderate?

There is more complexity to this story of course. The Fabian Dream part of our Elites’ thaali definitely started leaning towards a mimicry of Russia in the 1970s, but it was not a permanent mimicry. The Fabian Indians in the 20th century constantly oscillated between Ruskinism and Bolshevik Barbarism. Indeed, they played jump-rope with this line. So, for most of the 20th century, the শুদ্ধ equilibrium prevailed.

Eventually, due to a long list of complicated events (primarily the proliferation of social media breaking the iron-grip of the Legacy Elite over the minds of the people), the edifice of the শুদ্ধ Dream started cracking. The Demos, more educated and eager to have a say in the governance of their own country, started parsing through the details of the শুদ্ধ equilibrium, and were left in a state of confusion.

Why did the State employ the Brahmo Dream over the majority (essentially enacting Laïcité against them) but enacted Laissez-Faire for the minorities (in relation to one minority in particular)?

Why did the State grant some communities resources and complete freedom to manage their education, and not to others?

Unfortunately, the people of India started asking very অশুদ্ধ questions. And all they got from the শুদ্ধ elite in reply was cynicism, dishonesty and obfuscation. In the face of this groundswell of public opinion, the শুদ্ধ Dream retreated and started to bend, fulfilling the destiny owed to it by its creaky foundations.

Governing Gaul, and the deserved defeat

The broth prepared using the ingredients of the Brahmo Dream, the Fabian Dream and শুদ্ধ, brings us to the Legacy Elite of today. This is not to say that they were only influenced by these three sources or impulses. There were obviously many more variables, sometimes even going in opposite directions to the ones I’ve mentioned. But I do think that in the battle for the hearts of the Legacy Elite, these three Dreams have won out, at the cost of other Dreams like the fair and gracious one offered by Sri Aurobindo.

The amazing thing is, that most of these Elites are not consciously aware about the existence (or history) of their own Dreams. These Dreams function more as impulses, instincts, directions of thought, or pathos-based reactions to contemporary events. The average শুদ্ধ Hindu knows that the Partition of India was done on religious lines, but accepting this fact would make them feel what they have defined as “hatred”. They do not want to think of themselves as “hateful” people and so they willingly put on the শুদ্ধ blindfold. They are trying to convince themselves, as much as they are trying to convince us. But ideals, no matter how irrational, especially when they “feel” right, have a very sticky quality to them, especially for the young and the restless. So the শুদ্ধ Hindu will continue to exist for at least a few generations, till the embers of these Old Dreams truly die out.

As of today, the Indian Legacy Elite is staring down the barrel of defeat. The obvious contradictions in their views have led them to be decimated in the sphere of mainstream Indian electoral politics. They are in a ten-year-long exile now, but to their credit, they do not lack the will to fight. What we now observe is that as the “concern” in the West about “what is going in India” increases, the Indian Legacy Elite is finding that it can actually fail upwards.

Because the Indian Legacy Elite did go through one final transformation. In the 1990s-2010s period, the Indian Legacy Elite, in many ways, gave up on many Red aspects of its nearly one-hundred-fifty-year long Dream, to merge with the dominant worldwide Dream of the time: American (global) liberalism. Ideologically, it was not a very distant trip from Fabianism to Americanism, but it was a trip nonetheless. In this new equation, facilitated by the rise of American mass culture, mass media, and a growth in communication technology, the Indian Legacy Elite took up a role similar to that of the Governors of a Roman Province (like Gaul) during the Republic era.

Their job was to “manage” the province (India) on the behalf of the Republic (the global liberal regime), reporting on the behavior of the natives and making sure that the governed populace stays within the confines of ideological discipline. A great recent example of this attitude can be seen in two essays published in the “The Return of Civilizations” edition of Noema Magazine. As my friend Priyank Chauhan recently pointed out to me in a conversation, it is a truly damning indictment of the Indian Legacy elite that the two articles written by Indians in this series about the “return of civilizations” both refused to accept India as a civilizational entity in the first place. This is obviously in sharp contrast to the Chinese writers, who eagerly embraced their civilizational identity. If there was ever a perfect analogy for the difference in the two countries’ trajectories in the last fifty years…

Shashi Tharoor’s piece is exactly what you would expect from a Fabian elite that now function as frontier consulates of the American liberal regime. The only thing they know how to do is to make appeals to the ideals of the Empire: liberalism. In doing so, the Legacy Elite plays its hand: it shows us that it places liberalism as an ideal above the ideal of Indian civilization itself. As does Pallavi Aiyer’s piece titled Purity vs. Plurality in India. The Indian Legacy Elite deserves its ideological defeat.

Does the Indian Legacy Elite really expect the natives to believe that in a civilization-sized country, with a memory of at least 4,000 years, and a population of a billion and a half people, there is not even one, new, unique idea that can be shared with the world? Not even one? If we are not a civilization, then was John Strachey not justified in saying that “the first and most important thing to learn about India is that there is not, and never was, an India”?

Perhaps Malcolm Muggeridge was right: the last true Englishman is, and will be, an Indian. He will speak in the Queen’s English, and tell the western media that they (the west) are no longer liberal enough! This Brahmo, Fabian, শুদ্ধ Indian will fight for the Dream that he has internalized, even as he loses his control over the Province of India in the face of an unimpressed native revolt.

As we all know, this revolt of the natives, in the form of the emergent, chaotic, unorganized and reactive forces of Hindutva, has routed the Legacy Elite in the electoral field. In the minds of a lot of Indian people, this Dream is now dead. The only ones still holding out, as they always do in any intellectual tradition, are the Priests. In its creaking old forts like university professorships and editorial boards, the Legacy Elite looks like it is in the final stretch of its fight - like the last stand of the Druids before the complete Roman conquest of England.

In his recent book-launch event for “Revolutionaries: The Other Story of How India Won Its Freedom”, Sanjeev Sanyal mentioned that when he went to Penguin Publishing to publish his first ever book, every instance of the word “Hinduism”, was canceled out and replaced with “Brahminism”. It is in petty forts like these that the Legacy Dream continues to function to this day. They still undergo their daily praxis, fighting small battles to defend their Old Dreams. Defending these forts is their final stand. And one cannot help but admire their commitment, even if it is a commitment to someone else’s Dreams.

Perhaps it should be unsurprising that the Legacy Indian elite Dreams decayed, and eventually fell to the emergent forces of Hindutva. At its core, these Dreams were nothing but a shallow mimicry of the Dreams of other peoples and other Elites. These Dreams actually meant something to the Elite of the places they came from. They represented the economic, social and intellectual journey of a particular group of people. But in India, they were simply the consequence of the historical thumb of colonialism. They were imposed top-down on a particular set of English-educated Indians, who were swept away by the most seductive ideas of their time, and adopted the Dreams as their own: Nehru was a communist in the 1920s not because communism represented the emergent voice of the Indian people, but because most of the world’s elite was communist in the 1920s and 30s. Could Dreams built on successive acts of mimicry really have been expected to never lose their vitality?

Not only this, these Dreams lacked any sense of belonging to this nation, this civilization. They were never organic or emergent: economically, ideologically or spiritually. And the surface-level impact of these Dreams was such that even among the class where they had a hold, the Elite themselves, they eventually became nothing more than a means to personal ends. The goal of the members of the Indian Legacy Elite since the 1990s has essentially been to “graduate” from India and become a part of the western liberal elite. Should it really be surprising then, that they adopted the ideology of western elite power (progressivism)? Or that the natives of the outer provinces would not eventually see through the ruse? It could be the benefit of hindsight, but to me, this defeat of the Old Dreams has been dialectically inevitable since the first day of English-education in British India.

However, we also know that Hindutva as it exists today is too shallow to actually serve as a replacement Dream. It is too reactive, too negative, too oppositional and too confrontational. Hindutva has focused Hindu society’s energies towards only building Śatrubodha. It is not completely without use, because it offers an avenue for organization and discussion, a basic minimum platform of sorts. But it lacks direction. It has no normative Dream to show, even to its willing audience. It has very little to offer us in our Svayaṃbodha.

It has also noticeably still not captured the Legacy Indian elite, despite a decade of nearly unchallenged political power. And it will not do so until it can show them a New Dream. A Dream that has a tangible and positive vision for the future, a Dream that deprograms the cynical and ideological Legacy Elite and shows them a new possibility for the country: one built on Indic ideas, Indic impulses, and Indic Dreams. Is that really too much to ask for?

This, in many ways, is the goal of this movement that we call the Dharmic movement. It is not a humble goal, but in my opinion, goals and Dreams need to be maximalist. They need to break through the horizon of the current conditioning and bring about a complete paradigm shift. If they don’t, they will be swallowed up by the existing hegemonic Dream.

On that note of humility, I will end this part of my series. I hope you will join me in the final part, where I will make my small attempt to think through what this New Dream could look like!

धन्यवाद for reading!