# Bodhas

The Empire of Threads and Silver - How Colonialism Unraveled India’s Trade Legacy

7 January, 2025

1296 words

share this article

Exploring India’s Forgotten Economic Heritage, the Colonial Narrative, and Lessons for the Future

This article is the second in a series exploring the recently published book series titled Bharat Gatha, dedicated to the life and works of Sri Ravinder Sharma Guruji. Edited by Ashish Gupta ji and published by the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA), these books shed light on Guruji’s contributions as an artist, craftsman, storyteller, historian, educationist, sociologist, and economist in the native Indian context. Founder of Adilabad’s Kala Ashram, Guruji was honored with the Kala Ratna Award by the Government of Andhra Pradesh in 2014. Read Part 1.

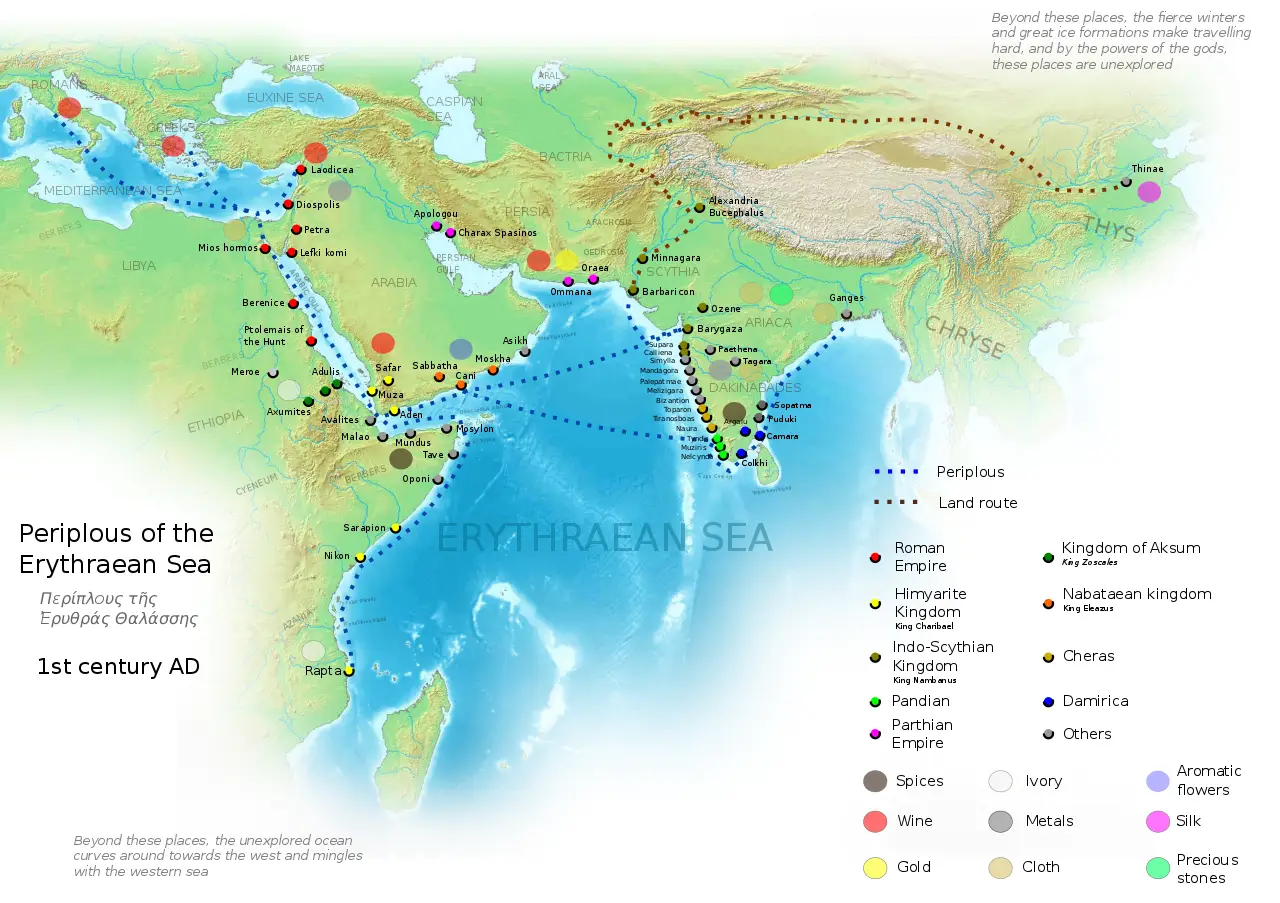

This map is derived from the book Periplus of the Erythrean Sea. It depicts trade routes in the ancient world, ports in the Chera territory and other parts of India, and the trade routes connecting them to other parts of the world along with the items of trade.

This map is derived from the book Periplus of the Erythrean Sea. It depicts trade routes in the ancient world, ports in the Chera territory and other parts of India, and the trade routes connecting them to other parts of the world along with the items of trade.In the grand narrative of India’s cultural and economic heritage, there lies a story often misrepresented and misunderstood. Picture a bustling ancient port city along India’s coastline—merchants negotiating deals, artisans crafting exquisite goods, and caravans loaded with textiles, spices, and metals setting off on long journeys. This image, though rooted in historical truth, has been overshadowed by the colonial narrative that reduced India to a land of peasants and subsistence farming. The question arises: was India always an agricultural society, or is this image a deliberate distortion crafted by colonial powers to serve their economic and political interests? This article, weaving together sociological insights and historical evidence from Ravinder Sharma (Guru ji), Dharampal, and Ananda Coomaraswamy, re-examines India’s identity as a nation of trade, innovation, and craftsmanship.

The Agrarian Myth: A Colonial Narrative

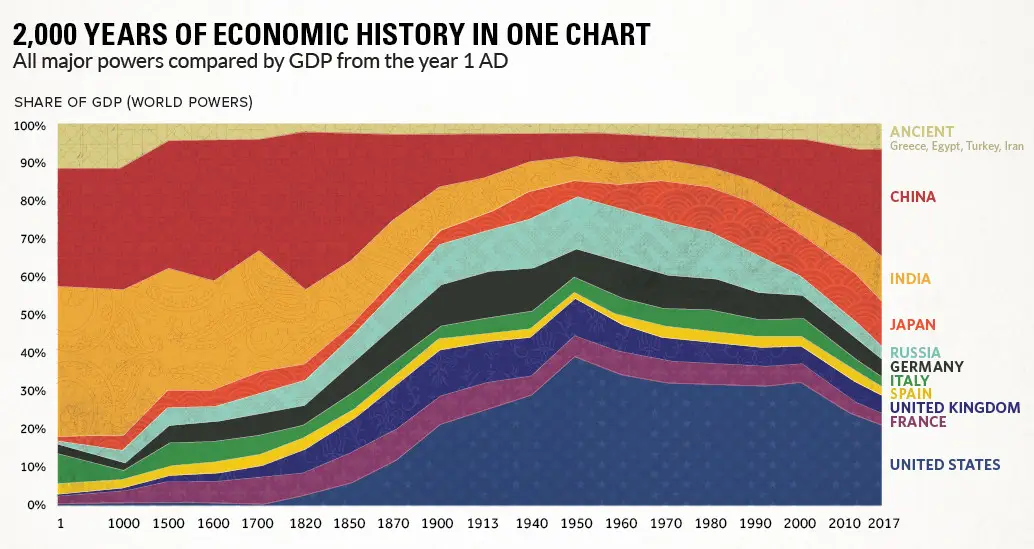

To understand how this misrepresentation took root, we must revisit the colonial lens through which India was portrayed. The British colonial administration deliberately constructed the image of India as a static, agrarian society, dependent on subsistence farming and a rural economy. This was not just an academic oversight but a calculated political strategy. Historical data, however, paints a very different picture. Angus Maddison’s research reveals that -

In 1700, India contributed 24.4% of the world’s GDP and 25% of global industrial output. By 1900, these figures had dropped to 4.2% and 2%, respectively.

This decline was not an organic process; it was engineered through systematic deindustrialization, forced restructuring of local economies, and economic exploitation.

Imagine a village artisan, once proud of his finely woven textiles, watching helplessly as British policies flood the market with machine-made goods. The famed Adilabad steel, renowned across the world and exported to Damascus for crafting swords, became obsolete under colonial trade practices. This wasn’t just an economic decline; it was a cultural rupture.

India: A Land of Trade and Industry, Not Just Agriculture

India has always been a nation of both agriculture and industry. The entire country thrived on craftsmanship. Labeling India merely as an agricultural nation was a colonial strategy to undermine its economic prowess.

Trade in India operated primarily through two significant routes:

- Waterways: Using ships and boats for international and coastal trade.

- Land routes: Through organized caravans, known as sārthavāha, for inland trade.

Scholars like Chandragupta Vedalankar documented these networks in his book Vrihattar Bharat, detailing the extensive pathways traders used for commerce and pilgrimage. These trade caravans were meticulously organized, with specific roles and responsibilities assigned to each participant. Today, remnants of this structure can still be seen in the Vārkari community, which maintains a similar tradition during the Vārikari yatra.

Through these routes, traders traveled abroad, exchanged goods, and returned with silver. This silver was equitably distributed within their communities. Over centuries, this cyclical tradition gave rise to shared cultural and economic practices. When the British disrupted these systems, the same trading groups were reduced to the Vaiśya caste, which was originally a diverse socio-economic group, not a monolithic caste.

Small Technology, Big Autonomy: India’s Unique Model

In traditional Indian society, technology wasn’t about domination; it was about integration. ‘छोटी टेक्नोलोजी’ (small technology) played a critical role in shaping local economies. Imagine a village blacksmith, surrounded by children observing the rhythmic hammering of hot iron. This wasn’t just labor; it was knowledge transmission.

Small Technology vs. Large Technology

- Small technology was localized, people-centered, and environmentally sustainable.

- Large technology, in contrast, is centralized, capital-intensive, and exploitative.

As Ananda Coomaraswamy described, these small technologies which found expressions in the work of artisan communities, were deeply embedded in the social fabric. A potter didn’t just create clay pots; they shaped community rituals, festivals, and daily life. Technology was not an external force; it was intrinsic to social relationships, ensuring dignity and autonomy.

Forest Communities: Integrated, Not Isolated

In colonial sociology, and even in contemporary sociology in India, forest-dwelling communities are often portrayed as ‘isolated,’ ‘primitive,’ or ‘separate from the mainstream.’ This view ignores a fundamental truth: India’s forest economies were deeply integrated with the larger socio-economic systems.

Visualize the vibrant trade networks of Adilabad’s tribal communities: hides, horns, forest produce, and oils being bartered for silver and textiles. Guruji’s research reveals how these trade systems weren’t peripheral; they were essential.

- Silver Trade: Tribals received silver in exchange for goods, creating complex but harmonious barter systems.

- Sārthavāha Tradition: Organized trade caravans carried goods across vast routes, enriching both tribal and non-tribal economies.

Guruji’s study highlights a fascinating insight: Adilabad’s tribal communities possessed significant quantities of silver. How did they accumulate such wealth despite the area having no silver mines? His investigations revealed that Adilabad’s tribals played a central role in managing cattle, crafting leather goods, and trading forest produce. Thousands of livestock were entrusted to these communities, and in return, they received grain and other necessities. When animals died, the tribals retained their hides, horns, and bones, which became valuable trade commodities.

Local artisans and traders, including communities from Bangalagiri, would visit the tribal areas annually, exchanging silver for hides and horns used in crafting products such as bangles and other artifacts. The tribes also harvested forest grasses, extracting oils that were highly prized in markets. Small, makeshift oil extraction units (bhatties) were set up in forested areas, where tribals would process these resources, receiving silver in return.

These intricate trade relationships weren’t primitive barter systems—they were highly organized networks that operated with precision and mutual trust.

Over centuries, these systems sustained local economies, creating an ecosystem of wealth distribution and environmental harmony.

Conclusion: India More Than an Agrarian Nation

India was never just a land of subsistence farmers. It was, and remains, a nation of traders, artisans, and knowledge-keepers. By revisiting these roots, India can reclaim its historical identity and offer a blueprint for global economic and cultural sustainability.

As Ivan Illich argued, modern industrial systems often alienate individuals from their tools and knowledge. In contrast, traditional Indian systems—centered around small, decentralized technologies—empowered individuals and maintained community autonomy. Illich’s critique of industrial gigantism aligns closely with India’s historical experience, where technology was not just a tool but an extension of social and cultural values.

It is time to move beyond the colonial caricature and embrace the truth: India was, and always will be, a nation of trade, innovation, and resilience.