share this article

Samuel Huntington in his Clash of Civilisations posits that “the fundamental source of conflict in this new world will not be primarily ideological or primarily economic. The great divisions among humankind and the dominating source of conflict will be cultural.” Verily, the most significant areas of conflict in the modern world are related to culture, and more narrowly, to the self’s interactions — in native as well as in foreign cultural environments — with institutions, ideas, and even extensions of the self, such as language.

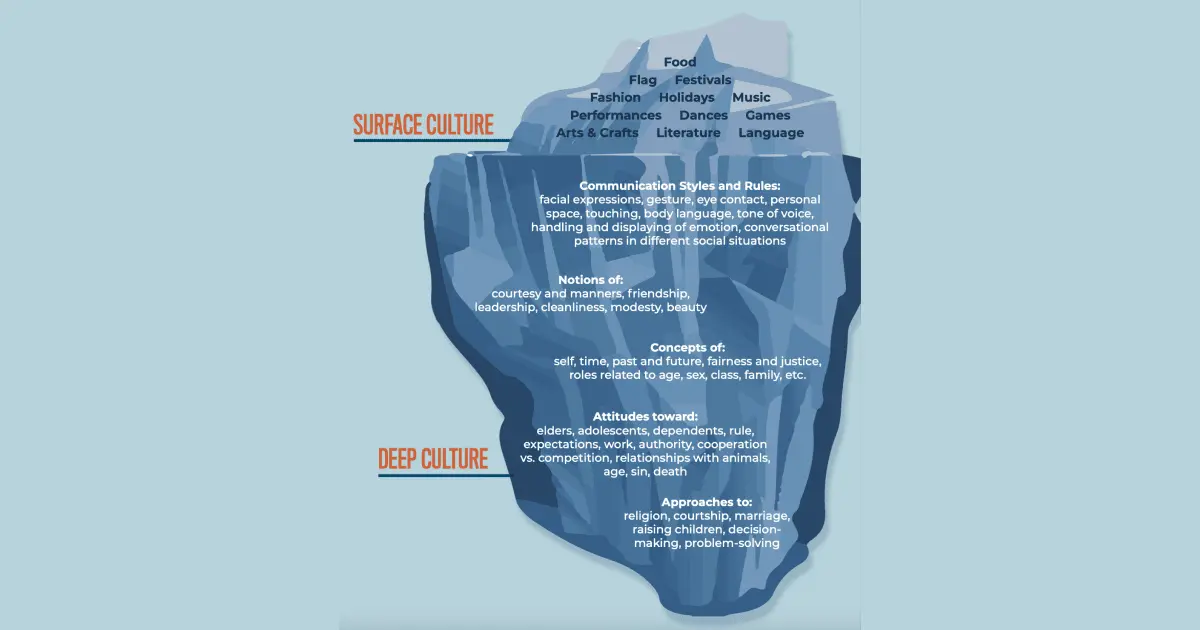

In the 1970s, anthropologist and cultural researcher Edward T. Hall imagined culture in the iceberg model with two components — only 10%, constituting the “external” or “surface” culture, is readily visible, while 90% is “internal” or “deep’ culture, hidden beneath the surface. The overtly observable elements of culture are those most evident, such as language, rituals, festivals, traditions, familial and societal structures, and the shared stories that are carried on through the generations. The covert, non-observable elements include the subtle yet more impactful aspects: shared assumptions, social cues, cultural norms, worldviews, attitudes, aspirations, and the fundamental values upon which the society itself is founded.

Another major model emerging from Hall’s work is his broader categorization of cultures based on their “context”, which is the most cited theoretical framework with respect to discussions on intercultural communication in the corporate world and in literature related to cross-cultural comparisons (though it is not without issue). Hall relates the cultural metrics of “high” and “low” context cultures in order to better understand the differences in communicative strategies and behavior among various cultures. In what he terms as‘high context’ cultures, those that operate with a high degree of presupposition, he says that “simple messages with deep meanings flow freely”, in contrast to low context cultures, such as Western societies, that require greater information to be transmitted or more context to be conveyed in order to transmit meaning. High context cultures therefore tend to be more collectivist, intuitive, and contemplative, with a stronger and more lasting sense of history and tradition, as opposed to low context cultures that are more individualistic, and shared experiences tend to change drastically from one generation to the next.

Language carries with it embedded cultural knowledge, and is significant marker of cultural identity. In fact, ritual in the Hindu conception is premised on the extraordinary powers of the spoken word and of sound itself — the śabda as a pramāṇa — and its ability to create avenues of communication “that extend our cognitive world far beyond immediate perception, and its ability to produce infinitely creative structures of recursive syntax by which new meanings can be generated” (Frazier, 2017). Just as language influences the speakers’ worldview (the linguistic relativity or the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis), so also, Hall theorizes, does the converse hold good. It is incontestable that cultural contextualization influences language and even non-verbal communication in tangible and heritable ways. Content, meaning and context during communication is often determined by cultural paradigms, and transmitted through language itself in combination with through societal conventions. Thinking in terms of Hall’s notion, the gradual loss of familiarity with indigenous languages have led to the creation of a discordant society, wherein all its members are not attuned to the same social cues, conventions, and mannerisms.

World over, low context communication is quickly becoming the baseline, the new normal. It is the inevitable consequence of the anglicization that Western corporate structures bring to any culture they set up in and interact with. In light of such observable truths, multiple scholars have criticised aspects of Hall’s model, especially his statement that low context cultures are more amenable to external influence and manipulation. The loss of “deep” culture, and the disappearance of unspoken context is the loss of culture as a whole, and is the reason for the downgrading of high context cultures into low context ones. Most societies in the world seem to be headed to this state of high entropy, erasing their own slates through the rampant adoption of the superficial milieu of a very unidimensional modern culture that characterizes the West today.

In many ways, Hall’s model is quite shallow and does not apply to the way in which culture operates and manifests in Hindu society. It fails to account for some post-colonial realities and foreign influence on indigenous cultures — it can only apply a cross-section of certain societies at specific points in time. It also cannot explain the complexity with which inter and intra cultural interactions take place to not only create but also perpetuate and evolve culture itself. If historical happenings are to be accounted for, Hall’s iceberg must be reimagined as a mass of melted ice, a pool where deep and superficial cultures are both made of the same water and cannot easily be distinguished.

However, the usefulness of the model also lies in its apparent simplicity. Despite its glaring fallacies, it nevertheless serves the limited purpose of giving a glimpse into the social manifestations of culture and providing a paradigm with which to analyse certain trends observed in the modern world. Culture can be linked to context, and context is wholly dependent on worldview, which in turn is based in knowledge systems. Using this phraseology it could be argued that some of the major problems that Indian society currently faces could be attributed to a gradual de-contextualisation, or the loss of the shared collective understanding and subscription to the Hindu worldview.

Anthropologist Clifford Geertz (1973) defined “worldview” as that which is inseparably integrated into the ‘ethos’ of the people, that which sets “the tone, character and quality of their life, its moral and aesthetic style and mood; it is the underlying attitude toward themselves and toward their world that life reflects”. The Hindu worldview is broadly, “a complex, multifaceted cultural style that characterizes Hindu life as experienced through particular Indic sets of beliefs and habits.” (Frazier, 2017) The belief is that the microcosm is a mirror of the macrocosm, and therefore must accordingly be reflected as such. To structure one’s life, society and cosmos in the dhārmic way is the only way to bring order to a chaotic world, and to manage our volatile relationship with the surroundings. To live is to construct a purposive life tethered to the puruṣārtha and one’s prescribed dharma, which is simultaneously well-established in intellectual thought as well as built up through embodied experience. As asserted by Jessica Frazier in her book Hindu Worldview, “structures of ritual and ethics give a normative shape to this complex cosmos, while narratives often explore the more subversive and ambiguous paths of human agency.” The Hindu precept therefore, optimizes the human condition by incorporating both the most fundamental and the most elevated of human desires arising from the depths of consciousness (similar to the theoretical basis of Maslow’s Pyramid).

Philosopher J. N. Mohanty divides Indian cultural practices into “high-level” and “low-level, while Frazier’s notion of cultural paradigms are those which she classifies as “explicit” and “implicit’ theory. The ‘explicit’ is a system of formal knowledge, whether oral or textual, that is organised as a systematic exposition and explanation of knowledge itself. It is characterised by consolidation of knowledge, along with its continual evolution, and includes metaphysical considerations, philosophy, and the knowledge of self. The implicit consists of broader frameworks that are in conformance with the explicit, “as part of the underlying rationale of an idea”.

She elaborates on the postulation as follows:

“The former explicit kind of theory is more likely to derive from educational cultures, and so from intellectual elites and upper classes; as such, it represents traditions of reasoning “and social identities associated with the cultivation of that specific activity. Philosophers the ‘intelligentsia’ in some form, educators and critics may all be producers of explicit theory that holds to the importance of specific ways of thinking, supported by shared reasons and reasoning. But the implicit kind of theory is more likely to arise in the culture at large, within a discourse that may be unattached to systematic disciplines of knowledge. Implicit theory that lies beyond the range of classical text has become important for scholars studying cultures that have not cultivated explicit traditions, but which preserve ways of understanding, analysing and communally applying good thinking through other forms of tradition.”

In the case of Hindu cultures, the content of the Sanskritic or śāstraic texts are reflected in other sources of theory such as cosmological narratives, practical sciences, vernacular songs and regional practices such as pūjas, vratas, etc. Theoretical ideas are “encoded and transmitted in ritual and liturgy, songs and recitation, cosmologies and lived geographies, as well as in the grammars and terminologies that are used on a regular basis throughout any given community.” Implicit theory, therefore, represents the marginal (relative to the explicit), and reflects a wider range of influence.

If this distinction, described variously by different scholars is considered valid, then we arrive at the conclusion that neither is a monolith, but rather, a mixed bag, with syncretism and pluralism characterising interactions. There are both practical and theoretical considerations at both higher and lower levels, in the implicit and the explicit. Both levels are intertwined, just as actions and their meanings and ritual and symbolism are, and therein lies the key to the survival of a culture.

There is an alarming, directly observable loss of the collective sense of culture, which is, in the case of Bhārata, the fading of the belief in the Hindu worldview, and all its forms of expression. This has led to the eclipsing of its surficial manifestations, like the erosion of topsoil in the absence of roots. As more and more of society is alienated from its deep culture, the outcome is that surface cultural elements such as language, ritual, festivals etc., are affected, either replaced by foreign popular culture(s) or secularised or lost altogether.

One concrete way to inject a revival of culture appears to be through a conscious augmenting of the relevant cultural context, through the reinstitution of knowledge systems to their rightful place. Conscious efforts at the individual level may only go so far, and must take place in addition to, and not as a replacement for institutional change. The incorporation of Indian knowledge systems — and indirectly, culture and its foundations — into education policy has the immense potential to shape our world and our future to reflect our ethos. The method of influencing culture in substantive yet subliminal ways is not to directly thrust the culture itself, and pray it sticks, but to project an awareness of the knowledge systems upon which it is founded, in the hope that it organically manifests as culture. The phenomenology of culture and all of its explicit manifestations are, after all, dynamic rather than static, and inextricably linked to knowledge, the very basis of our civilisation. We can begin by rediscovering all our myriad storytelling traditions, reviving our languages, rituals and festivals and paying close attention to the knowledge, practices and responsibility conferred by our lineages, the devotion and loyalty carried through our sāmpradāyas, and the wisdom of our ancestors. Through the work we undertake, Bṛhat hopes to create lasting and self-perpetuating civilizational change. Our primary concerted effort, therefore, is to bring attention to the lacunae in our education and attempt to meet the demand for a deep-rooted, institutional change. In translating human action and in actualising human potential, we see cultural leadership as the only way forward.

References:

Cardon, P. W. (2008). A Critique of Hall’s Contexting Model: A Meta-Analysis of Literature on Intercultural Business and Technical Communication. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 22(4), 399–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651908320361

Hall, Edward T. Beyond Culture. Anchor, 1976.

Frazier, Jessica. Hindu Worldviews: Theories of Self, Ritual and Reality. United Kingdom: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017.

Mohanty, J. N. “Epilogue: Culture Theory and Practice: A Framework for Inter-Cultural Discourse.” In Cultural Otherness and Beyond, pp. 229-241. Brill, 1998.

Image url: https://www.ciee.org/sites/default/files/content/documents/wat/culturaliceberg.pdf