Precolonial History of the Dharmaśāstras

26 July, 2024

2406 words

share this article

This article is Part 2 of a series on the codification of law in India. Read Part 1 here. This piece shall cover a brief history of the Dharmaśāstra tradition as it existed prior to colonial rule, as only then can the true extent of what has been lost be comprehended. Though ancient, the Dharmaśāstra remain vital repositories of timeless wisdom responsible for economic prosperity, marriage, religious and spiritual contentment and social organisation and harmony. The notion of Dharma is alive as a powerful force of consciousness, invoked with reverence even in contemporary India. Dharmaśāstra has historically shaped state policies, social contracts, and carved an idea of justice and righteousness. Through this study, Dharmaśāstra shall be explored in an effort to bring out their contemporary relevance.

Dharma is both religion and law — the two are inextricably intertwined — and authoritative due to being based on eternal rules that sustain cosmic order, or ṛta. Every Hindu’s life is pervaded by Dharma - influencing all aspects of life, setting the path for righteousness, and embodying the moral and natural order. The Vedas are the ultimate source of Dharma, to which all statements may be traced, and the remaining sources are smṛti (including the purāṇas and dharmaśāstras), sadācāra or custom, and ātmatuṣṭi (conduct according to one’s conscience). The Dharmaśāstras contain all the immutable and eternal dharma that is expounded by the Vedas.

Literary Corpus

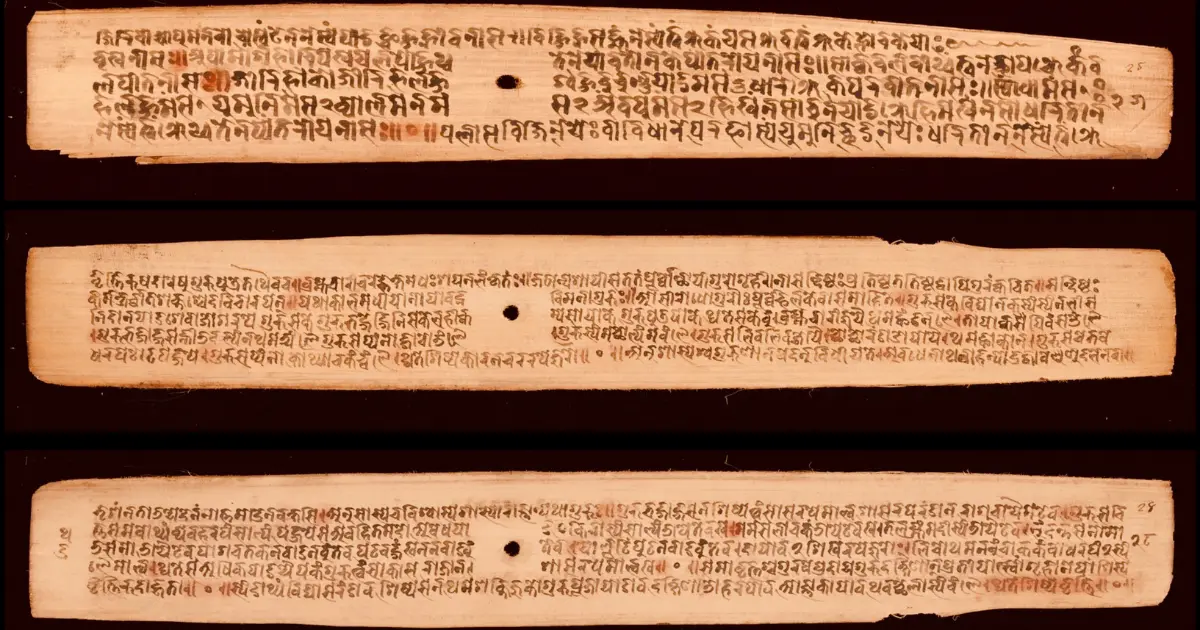

Dharmaśāstra literature in turn comprises of four types: dharmasūtras, the metrical smṛtis/dharmaśāstras, bhāṣyas or commentaries, and nibandhas or legal digests. Dharmaśāstra texts are a vast range of texts, produced over centuries in different regions of India, the tradition continuous through scholars. In her work, Appropriation and Invention of Tradition: The East India Company and Hindu Law in Early Colonial Bengal, Nandini Bhattacharyya-Panda observes that “the origin and development of the Dharmaśāstras are shrouded in uncertainty and myth”, as they lack a definitive historical origin — though it is widely accepted that the earliest metrical smṛti, which is also the most authoritative and explicitly legal text, is the Mānavadharmaśāstra or the Manusmṛti, attributed to Manu Svāyambhuva. This, along with the other original Dharmaśāstras such as the Yājñavalkyasmṛti, Nāradasmṛti, Viṣṇusmṛti, Kātyāyanasmṛti, Parāśarasmṛti, Vṛhaspatismṛti, are said to have been compiled between 500–400 BC and 800 AD.

The Dharmaśāstra tradition was composed of two broad schools of thought—the Mitākṣarā and Dayābhāga. Regions such as Uttar Pradesh, Orissa, and southern India followed the Mitākṣarā tradition, whereas Bengal predominantly followed the Dayābhāga. Bhattacharya-Panda observes that “intense intellectual debate and discussion contributed both vitality and durability to these traditions”. The two schools laid out certain principles regarding inheritance, property, marriage, succession, and other such legal categories.

Is Dharma Law?

A Sanskrit equivalent to the term ‘law’ cannot be found even if one scours through the Dharmaśāstra texts and treatises on vyavahāra with a fine-toothed comb. Dharma and law are not terms that can be used interchangeably, and the misconstruing of dharma as “religious law” by the British is a misconception that still persists today.

Derrett defines the Western notion of law as follows:

Law is the body of rules (namely positive and negative injunctions, commands and prohibitions), which can be enforced by judicial actions.. What ought (in some people’s opinion) to be law, is not law. Pious hopes or fears are not law. Ethical injunctions are not law. That which is left to choice is not law.

As stated by Bhattacharyya-Panda, what Derrett described as ‘not law’ are in fact precepts, and that the prescriptive and normative rules expounded in the Dharmaśāstras lack the quality of instrumentality or the coercive element that forms an essential component of law. She states that the acceptance of vyavahāra treatises of the Dharmaśāstra, which prescribed righteous modes of resolving disputes in compliance with scriptural principles as well as customary practices, suggests that śāstrika procedures were not treated as laws. The legal elements of the Dharmaśāstra were reflected in compendia on vyavahāra, variably translated as litigation (by JDM Derrett) and as justice (by Halhed). In addition, since disputes were to be resolved through the intervention of the king or an arbitrator — called a prādviveka — and not on the basis of a fixed statute or law, it is clear that śāstrika prescriptions were never envisaged as law in the sense that the 18th century British understood the term.

Derrett also offered an explanation for why the colonial officials mistook Dharmaśāstra as religious law: they considered the śāstras to be akin to canon law because they lacked the “inward knowledge of the civilization they undertook to protect”. Lariviere took issue with Warren Hastings’ attempt to restrict dharma to a short list of topics that were codified and translated under the category of law. He stated that “until the British invented it, there was no such thing as Hindu law.”

Paṇḍitas and Paramparā

Pre-colonial evidence demonstrates that the Dharmaśāstra tradition evolved as one of philosophy and intellect rather than for administrative exigency. The tradition survived, evolved, and flourished uninterrupted over millenia due to multiple reasons. The first was the necessity of the role of the paṇḍitas as interpreters of the Dharmaśāstra to accommodate the changing social needs. The second was that the nibandhakāras (commentators) had autonomy, and transmitted knowledge through the pedagogy of the gurukula system. Large numbers of institutions or centers of excellence for learning and transmitting the various branches of Dharmaśāstra flourished across Bhārata, run by communities of paṇḍitas or scholars known as tolas or ćatuṣpāṭhīs. Third, pundits were traditionally appointed as advisors to the king, tasked with referring to śāstrika texts to vindicate or dismiss the applicability of a specific rule.

Following the arrival of the British officials and administrators in the 18th century, there was a sharp decline of this tradition due to multiple factors. Paṇḍitas and translators appointed by the British for the task of codification could not employ pre-colonial methodologies such as the application of the philosophy and logic of nyāya and mīmāṁsa. During colonial rule, paṇḍitas were appointed to interpret śāstrika laws, but they neither had the final say on the matter, nor did they exert any influence on the judgment. According to Bhattacharya-Panda, “Their opinions were subject to the preferences germinne to the ideology and policies of the colonial rulers”. British “experts” of Hindu law saw paṇḍitas as an impediment to the delivery of justice. They labored under the delusion that the texts were “law” and that the tergiversating paṇḍitas were simply cherry-picking texts so that a decision could be reached that supported their opinion, and sought to eliminate reliance on the paṇḍitas. The colonial administration therefore, made great efforts to translate and codify the original Sanskrit texts in order to make Hindu law accessible to British judges. When the practice of appointing paṇḍitas in courts to advise judges was abolished by Act XI of 1864, “the traditional scholars lost their occupation, their philosophical fervor, their students, their patrons, and their glory.” Lariviere states that the British “mistrust and eventual rejection of the pundits interpretation of dharmashastra marked the end of any possibility that the rules governing society before the advent of the British would continue to be in force and continue to be applied to the populace.”

Interpretation, Application and Evolution of Dharmaśāstras

Certain rules of interpretation exist that are specific to the Dharmaśāstras such as the rules without an apparent or obvious purpose (adṛṣṭārtha) given more weight than those with (dṛṣṭārtha). According to Lariviere, it cannot be said with certainty what the actual law was in the subcontinent at a given moment in history. However, it can be said the dharmaśāstras laid the theoretical foundation of the legal system at any given moment. They are not statements of substantive law as actually applied, but rather, are theoretical guidelines, recorded following an elaborate process of observation of different sections of society, interaction with custom, practice and evolution, that served to show how the king and his subjects might adhere to dharma.

In contrast to the Western system of law, Hindu dharma lacked a centralized legal hierarchy or ecclesiastical authority that enforced the law. It was interpreted by local experts who remained sensitive to local circumstances, and used to inform and validate decisions. Lariviere states that the purpose of the legal system was not so much to deliver justice but to ensure that each individual followed dharma in the unique manner prescribed to them.

When it came to interpretation of law, commentators and digest writers held significant power. Dharmaśāstra tradition was not a static one — it evolved over centuries and millennia through ṭīkas (commentaries or exegeses, usually focused on a single text) and nibandhas (treatises or digests of multiple dharmaśāstra texts). Lariviere writes that “the pundits of old used their hermeneutical techniques to keep the dharmashastra alive and relevant to what they saw as the ever-changing daily needs of society. It was their concern to preserve the timeless ‘world order’ they saw in the idea of dharma.” Bhattacharya-Panda details the manner in which this process takes place. The authors of ṭīkas were tasked with resolving contradictions using the logic of nyāya and mīmāṁsa, and often offered varying interpretations based on the era and the region. The authors of nibandhas on the other hand had the monumental task of sifting through vast swathes of Dharmaśāstra literature to organize, classify and present rules of dharma. Bhattacharya-Panda points out that the unabated proliferation of nibandhas of the Dharmaśāstras from the 10th or the 11th century onwards until the mid-18th century indicates the existence of a vibrant intellectual tradition and the pre-eminence of the brāhmaṇas and the paṇḍitas in expounding the śāstrika rules. Bhattacharyya-Panda states that can be discerned from the writings of early British ideologues and administrators that “even the Mughal rule did not attempt to integrate this tradition within the state hierarchy of command and control and instead respected the autonomous domain of the śāstras.”

Orientalist Interaction with the Dharmaśāstras

The British attempt to govern and exploit the people, resources and institutions of the subcontinent occurred at the expense of traditional and orthodox institutions, and this especially holds true for the realm of law. The British were responsible for the obliteration of the living dharmaśāstra tradition and the crippling of its once vibrant schools and scholars. Lariviere poignantly observes that the tradition has not been resuscitated in independent India. The ill-intentioned quest was undertaken to eliminate the inconsistencies and systematize the traditional Hindu legal system, the to replace the guidance of the paṇḍitas with the precedent of the judge.

Nelson, in his A View of the Hindu Law, wrote that

Far from simplifying the British Judges’ tasks, recourse to Sanskrit texts which were inaccessible except by way of translation had created greater difficulties. In order to extricate themselves, the Judges had often been led to abandon this alleged written law in order to substitute for it their own sense of equality. This method had given rise only to arbitrary and incoherent decisions. An artificial law resulted from it, a veritable monster engendered by ‘Sanskritists without law and lawyers without Sanskrit’. [emphasis added]

The selective appropriation of the Dharmaśāstras to construct an artificial concept of ‘Hindu law’ marked a fundamental intellectual deviation from the past. Colonial digests were feebly devised corpora juris out of wide, misconstrued inharmonious materials. Bhattacharyya-Panda argues that the “colonial codes and the translations completely transformed the pre-colonial tradition of the Dharmaśāstras and Smṛtis. From being prescriptive, normative, and moralistic codes of conduct, selected rules expounded in such literature were assigned the new role of performing as law for a group of people generically called the Hindus.”

Bhattacharyya-Panda further writes, “It is significant that immediately after the codification and translation of fragments of the Dharmaśāstras into civil and personal ‘laws of the Hindus’ on property, inheritance, succession, marriage, and contract, the main literary activities in this tradition became confined only to translating the prominent treatises of Jīmūtavāhana, Kullūkabhatta, Raghunandana, Srikṛṣṇa Tarkālankāra, Vijñaneśvara, Vācaspati Miśra, and a few others on the Dayābhāga and Mitākṣara as well as the original Smṛtis (mainly Manusmṛti and Yajñavalkyasmṛti). Indian participation in this new enterprise, then, was minimal. The tradition of writing original treatises became either insignificant or extinct immediately after the consolidation of the colonial rule.” Translations commissioned by the British violated the original meanings of the words in the text and adopted British legal terminologies, carrying erroneous orientalist perceptions of law and society, which led to endless confusion in settling legal disputes.

The categories of law created by the British, such as those enumerated in Hastings’ Plan of 1772 — inheritance, marriage, caste, and other religious usage or institutions — to be derived from the dharmaśāstras were precisely the parallel to those that would have been within the jurisdiction of the ecclesiastical courts of England until 1857. Naturally, the same subjects were reserved for the local ecclesia as those reserved for the church in 18th century England. The British also mistakenly assumed that just as ecclesiastical law was applicable uniformly to all followers of the Church of England, Hindu law was internally consistent, and uniformly applicable to all Hindus everywhere. They assumed that the dharmaśāstras could be restricted in their application to these few topics rather than recognize its ubiquity, as its role in guiding every aspect of a Hindu’s life.

Moreover, when Dharmaśāstra was found to be in conflict with custom or social practices — called lokavyavahāra by Raghunandana — the latter always prevailed. The British application of Dharmaśāstra threw all pre-colonial conventions out the window. British compilers and translators took pride in asserting that the codifications epitomized remarkable continuity and that the translations were faithful renderings of the Sanskrit digests, though this could not be further from the truth. Texts were interpreted literally rather than using nyāya and mīmāṁsa, original texts were given importance over nibandhas, older texts over newer (opposite to the traditional convention), written rules prevailed over oral, and śāstra was given precedence over custom (or in other words, centralized rules over the more localized), in a complete antithesis to the manner in which Dharmaśāstras were traditionally applied in Indian society prior to the colonial interaction.

The next part in this series shall discuss the method and impact of the codification and the secularization of hindu law in colonial India.

References

- Bhattacharya-Panda, Nandini, Appropriation and Invention of Tradition: The East India Company and Hindu Law in Early Colonial Bengal (Delhi, 2007; online edn, Oxford Academic, 18 Oct. 2012)

- Lariviere, Richard Wilfred. Common Sense and Legal History in India: Collected Essays on Hindu Law and Dharmaśāstra. India: Primus Books, 2022.

- N.B. Halhed, A Code of Gentoo Laws, 1777

- Derrett. (21 Jun. 2024). Essays in Classical and Modern Hindu Law. In Essays in Classical and Modern Hindu Law. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. Retrieved Jul 21, 2024.

- Lariviere, Richard W. “Justices and Paṇḍitas: Some Ironies in Contemporary Readings of the Hindu Legal Past.” The Journal of Asian Studies 48, no. 4 (1989): 757–69