Codification of Law in India, Part 1

25 June, 2024

3498 words

share this article

The common law is not a brooding omnipresence in the sky, but the articulate voice of some sovereign.

* Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Southern Pacific Co v Jenson 1916: 222.

This article is part of a series on the codification of law in India which explores the colonial-imperial project of the codification of law, and its effect and continuing relevance, especially in light of the recent decolonisation narrative surrounding the recent enactment of the three revised criminal codes. It is through law that the dispossession and disenfranchisement of colonized peoples takes place, and it is through law and its various institutions by which colonial, imperial programs and policies continue to be reinforced and sustained. In the same vein, law has the potential to ‘decolonize’ the state and society.

In our quest to understand what it means to decolonise law, we must first examine the manner by which English law was imposed and the indigenous law it replaced. The present article summarizes the history of codification, its impact and the internal power dynamic between the colonial state and subject. The next article in this series shall explore the codification of personal law, with a special focus on Hindu law and Dharmaśāstra.

Codification of law is the process by which rules and laws are compiled and organized into a formal code. It is generally regarded as a form of modernisation and nation-building, but in the case of India, it was an imperial project and an endeavor towards uniformisation of law. Codification was used as a tool by the British to shape Indian society in their image. Macaulay was especially convinced that a code of laws was a critical instrument in the transformation of Indian society. He proclaimed in his speech before the Parliament: “I believe that no country ever stood so much in need of a code of laws as India.” Codified laws are vital examples of the lasting power of colonial institutions — most of them remain in force today; therefore, the history of codification in colonial India holds critical contemporary relevance.

History and Method of Codification of Law

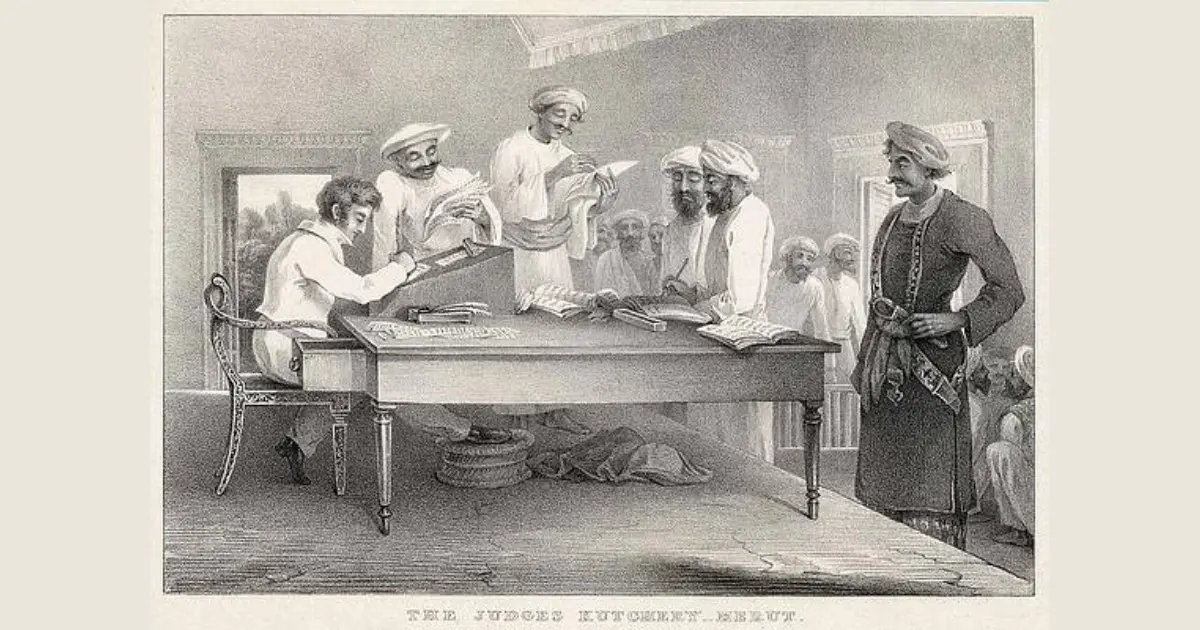

The preamble of Regulation XLI of the Cornwallis Code of 1793, passed in 1797 expressed the need for the codification of law, both substantive and procedural (which Bentham styles as ‘adjective law”), in India. “It is essential to the future prosperity of the British territories in Bengal, that all Regulations which may be passed by the Government affecting in any respect the rights, persons or property of their subjects, should be formed into a regular Code, and printed with translations in the country languages.. A Code of Regulations framed upon the above principles will enable individuals to render themselves acquainted with the laws upon which the security of the many inestimable privileges and immunities granted to them by the British Government .. and the causes of the future decline or prosperity of these Provinces will always be traceable in the Code to their source”.1 These 1793 provisions, originally made for the compilation of Regulation Codes in Bengal were subsequently extended to apply to Bombay and Madras, and, instead of removing the confusion and uncertainty of law, worse confusion ensued. The local colonial courts in India often administered via a variety of laws, with some that overlapped and were even contradictory both in principle and practice. Judicial officers were not only untrained and inefficient, but also found difficulty in ascertaining which law to apply, due to this plurality of sources. There was also a glaring inconsistency among judgements due to a lack of documentation of existing statutes and precedent. Thus, too much was left to the whims of the judges, leading to what Macaulay disparagingly called “judge-made law”, which he viewed as a “curse and a scandal”.

Subsequently, in 1833, Thomas Macaulay in an impassioned speech in the British parliament proclaiming that England’s greatest gift to India was one of a rule of law. He stated that the duty of the British was “to give good government to a people to whom we cannot give a free government”2. In pointing out the administrative issues faced by the East India Company in India, Macaulay presented his ideas about codification, to create “one great and entire work symmetrical in all its parts and pervaded by one spirit” — which reflected the influence of Jeremy Bentham, who echoed the belief that the process of codification, if accelerated in India, would bring about the same in England, in a sort of a reverse influence3. Due to political and public opposition back at home in England, codification had not been taking root there as quickly as it was in India, through a thoroughly undemocratic imposition. Macaulay himself iterated this when he proposed to Parliament the necessity for the colonial government’s “enlightened and paternal despotism,” being best suited to codify Indian law:

A code is almost the only blessing-perhaps it is the only blessing which absolute governments are better fitted to confer on a nation than popular governments. The work of digesting a vast and artificial system of unwritten jurisprudence is far more easily performed, and better performed, by few minds than by many. … A quiet knot of two or three veteran jurists is an infinitely better machinery for such a purpose than a large popular assembly, divided, as such assemblies almost always are, into adverse factions. This seems to me, therefore, to be precisely that point of time at which the advantage of a complete and written code of laws may most easily be conferred on India. It is a work, which cannot be well performed in an age of barbarism. It is a work which especially belongs to a government like that of India — to an enlightened and paternal despotism.4

Codifiers in colonial India drew from Livingston’s Louisiana Code and Field’s New York Code; Whitley Stokes, who held the high post of Law Member of India, dedicated his book, The Anglo-Indian Codes: Substantive Law, to “all who take an interest in the efforts of English statesmen to confer on India the blessings of a wise, clear, and ascertainable law, and especially to those who are interested in what is still, in London and New York, the burning question of Codification.” Codofiction was a project whose pressing need was recognised across the world.

History of Civil Procedure Code

Prior to the 1st of July, 1859, there were no less than nine different systems of civil procedure simultaneously in force in Bengal: four in the Supreme Court, for its common-law, equity, ecclesiastical and admiralty jurisdictions respectively; one for the Court of Small Causes at Calcutta; one in the military Courts of Requests; and three in the Courts of the East India Company, one each for regular and summary suits, and a third applicable to the jurisdiction of the Deputy Collector in what were called resumption-suits (or lá-khiráj suits)5.

The outcome of Macaulay’s speech was the constitution of a codification commission in England and in Section 53 of the Charter Act of 1833, a provision for the appointment of a Law Commission to enquire into “the jurisdiction, powers, and rules of the existing courts of justice and police establishments in the said territories, and all existing forms of judicial procedure, and into the nature and operation of all laws whether civil or criminal, written or customary”6. The Law Commissioners so appointed drafted a code of civil procedure, and an act regarding the law of limitations. Thereafter, a second Law Commission constituted by virtue of the Charter of 1853 to analyze and make recommendations based on the work of the previous commission. The combined output of the two commissions was the enactment of a Code of Civil Procedure (Act No. VIII of 1859), the Limitations Law, a Penal Code and a Code of Criminal Procedure.

The 1859 code was intended to apply to ordinary civil courts of the provinces of Bengal, the amalgamated courts of Presidencies of Madras and Bombay (called the High Courts) as well as to the ordinary courts of the North-Western Provinces, however, it was drafted to exclude the Supreme Courts in the Presidency Towns and to the Presidency Small Cause Courts. It was thereafter extended, to the whole of British India, to the High Courts in all their civil matters. The 1859 code was soon found to be “ill-drawn, ill-arranged and incomplete”7, and it was replaced by the 1877 code which once again required several amendments and therefore was re-cast as the 1882 code. The 1908 code was the result of a couple decades of experience with the operation of the 1882 code, and improved upon it, laying to rest certain discrepancies and conflicts regarding the interpretation of certain provisions. The Committee constituted, presided over by Sir Earle Richards, made no radical changes but rather, made certain modifications and rearranged the provisions of the code into sections8. This Code of Civil Procedure continues to be in force today, and was last amended in 2018.

Codification of Criminal Law

Four Indian Law Commissions worked intermittently on the Anglo-Indian Codes from 1834 to 1879. One of the most important contributions of the first Law Commission was the Indian Penal Code, submitted

by Macaulay in 1837 and passed into law in 1860. Codification of the criminal law did not stem from an

ongoing reform process but from prevalent legal ideas about “native feelings and prejudices.” Colonial lawmakers such as Macaulay and Maine believed that the reform of the criminal law would meet with the least social resistance given that crime was universally understood whereas civil law touched upon what Maine called “the local peculiarities of the country.” Because it was assumed that natives would not have the same prejudices about criminal law as they did about civil law, the Indian Penal Code (1860), the Code of Civil Procedure (1859), and the Code of Criminal Procedure (1861) were the first three codes enacted by the colonial government.

The Code of Criminal Procedure passed in 1861 secured the legal superiority of “European-born British subjects” by reserving for them special privileges such as the right to a jury trial with a majority of European jurors, amenability only to British judges and magistrates, and limited punishments. These fiercely guarded “privileges” — or “rights” — as they were alternatively described, made the law both a symbolic and a literal marker of imperial power: European subjects were literally given special privileges that distinguished them from Indian subjects; symbolic due to their significance in preserving and showcasing European power and prestige. Kolsky remarks that: “The debates about uniform criminal jurisdiction poignantly illustrate how abstract universal theories ceded to the concept of “Indian human nature” and equal legal protections became embroiled in the European community’s struggle to differentiate itself from the colonized subjects of India. Amended several times during the nineteenth century, the Code of Criminal Procedure continued to sustain a system of racial inequality according to the inverted logic of colonial difference. As one Member of the Legislative Council tellingly put it, “equality was a miserable sham” if it meant that Europeans and Indians would be set on an equal footing before the law. Various Indian inversions defined the arguments of those opposed to uniform criminal jurisdiction: equality became inequality; the “doctrine of equal laws for all” was compared with the “actual state of things”; and racial distinctions were renamed “safeguards,” the removal of which would purportedly increase existing inequalities rather than make all men equal before the law.”

The Purported Necessity for Codification

The British saw the linguistic, political, religious, legal and social diversity they encountered in India as a hindrance to the consolidation of their power and undertook a uniformization project through various reforms. They argued that codification would bring order to the chaotic subcontinental legal framework by replacing the arbitrary and personal will of the Oriental despot with the rational and reliable objectivity of a universal law. The civil and criminal procedure codes were, in their opinion, in need of codification and systematization in order to better aid their own administrative practices. To this end, codification embodied the civilizing mission, and a method of non-coercive control over the native populations that were otherwise capable of mounting a revolt against the foreign rule.

Ideas about Indian history and culture were evoked to argue that “the principle of equality is not applicable in the present state of India,” because “the principle of equality has no application among the Natives themselves, as their domestic and social institutions prove.”9Rather than representing the abstract efforts of metropolitan legislators to create a “science of legislation,” the work of codification in India therefore, was prompted by the burgeoning problem of European criminality and shaped by the colonial insistence and racialisation of the peculiarities of Indian culture. ‘East is East’ they claimed: “our thoughts are not their thoughts, nor are their ways our ways.” Colonial justice was described as “immeasurably superior to anything they [Indians] had ever had before”.10

The colonial propensity for documentation and codification extended across disciplines, whether it was of the literature and texts, languages, cultural traditions, or the subject of the present discussion — of legal procedures, systems, and customs. Codification was an objectification and classification of traditions that facilitated their further representation, reference, and organization, for use as channels of control. They drew from the Hindu Sanskritic texts and legitimized their power through the application of the law thus derived. Their favor of written over oral traditions, in effect altered the indigenous conception and nature of the Dharmaśāstras and the law therein contained. The British derivation of authority in texts secured for them not only symbolic but also real power as well. As stated by Robert Yelle, “the effects of this textual voice on both Hindus and British is a noteworthy legacy of colonialism. This bias distorted the actual shape of Hinduism, displacing living traditions in favor of the written in standard that in many cases was ancient, irrelevant or even incomprehensible to many Hindus.”11

Extrapolating this to Hindu law (whether public or personal), it may be stated that the derivation of authority solely from textual sources, with a preference for antiquated sources over the more recent, was in direct conflict with the Hindu worldview, wherein law was seen as evolutionary, and was rarely applied in letter, but rather in spirit, conforming to general ideas rather than specific prescriptions. Therefore, codification as an exercise was not only in effect, the imposition of foreign law but also irreversibly altered the manner in which textual sources of indigenous law are analyzed and applied. What seems like painstaking efforts to codify law and the judicial system was in fact a not-so-subtle way of better understanding a nation that could then be subjugated, controlled, and ruled. Language and information were vehicles of control, made obvious by the apparent connection between knowledge and power12.

However, fearful that codification would make the backward civilization of the colony more modern, force an enlightened and paternal despotism to make legal rights more accessible to colonized peoples. and transform Indian subjects and British citizens into legal equals, the purportedly universal character of codification in India was consistently infused with colonial ideas about “Indian nature” and difference. In other words, a uniform rule of law would profoundly threaten the power dynamic that distinguished colonizer from the subject.

Impact

Pre-colonial legal arrangements varied across time and place, and there were multiple sources of judicial authority (Cohn, 1961). Nicholas Dirks, in the foreword to Cohn’s Colonialism and Its Forms of Knowledge: The British in India, summarily states that “the objectification of India, like the subtle and sinuous relations of knowledge and power, is perhaps most directly visible in the institutional domains of revenue policy and legal practice”13. Therefore, the codification of law (such as that undertaken for Criminal and Civil Procedure), presented as a much-needed judicial and legal reform for the British Raj, was in actuality, an imperial imposition that had lasting deleterious effects on the diversity and operation of laws, legal systems and fora in India. The “rationalization” and anglicization of law in India was used as a justification for British rule: law was construed as necessary in order to provide India with order and stability in a supposedly chaotic and anarchic state that characterized the pre-British days. Colonialism, therefore, could be repackaged as something that benefited the country, while drawing attention away from the brutal policies of economic exploitation that characterized colonial rule.

In her work Strategies of Control: The Case of British India, Valerian DeSousa states that Anglo-Indian law instated by the British was an “ideological” strategy of control (Althusser, 1971), and served to reinterpret traditional Indian law in terms of British legal philosophy, reconstitute Indian subjectivity and irreparably alter traditional relationships to more effectively serve British interests14. This was avowedly similar to the manner in which the imposition of an English-based education system succeeded in creating colonial subjects that were subsumed in the ideological discourse perpetrated by the British. Codification was initially supposed to take into account customary law, but that idea was quickly abandoned due to the complexity of the task and its impracticality. Instead, there was an exercise of reinterpretation of the sacred laws of the Hindus and customs through a lens of British philosophy, jurisprudence and attitudes, leading to a more rigid, secularized law, one that did not incorporate ritual prescriptions, customary laws, unwritten or oral traditions and practices, and informal legal forums. Thus, effectively, Anglo-Indian law was born, and replaced indigenous law, which was in contrast to Anglican law, founded on principles of flexibility and judicial discretion. Where the code did incorporate indigenous law, it was inconsistent or inadequate in intent and effect. As Anglo-Indian law, its institutions, and practices gradually replaced indigenous legal apparatuses, its effect was an alteration of the very relationships that individuals and groups traditionally held with each other and with the state, thereby reconstituting their very subjectivity.

Conclusion

Elizabeth Kolsky remarks that the codification project brought to the surface “internal tensions in liberalism and empire. The paradox of attempting to create democratic legal institutions in the context of absolute authoritarianism manifested itself with striking clarity in the debates about the Code of Criminal Procedure. Good ideas in theory, legal equality and uniform criminal jurisdiction were proclaimed to have no place amid the peculiar circumstances of India where different histories and different cultural understandings made “equality” a relative rather than absolute principle”15.

In retrospect, the codification of law was a key landmark in the development of the Anglo-Indian legal system in India, and a watershed moment in the colonial reinforcement of power. It changed the course of history, and invariably led to a fundamental restructuring of indigenous law and the legal system. The overall economic and social impact on the subjects of the laws, along with the implications on justice itself are beyond the scope of this paper, however, codification of law must be viewed with the same measure of distrust as the wholesale imposition of British laws were, in light of their enduring influence on post-colonial legal systems.

Footnotes

- Regulation XLI of the Cornwallis Code of 1793, A Regulation for forming into a regular Code all Regulations that may be enacted for the internal Government of the British Territiories in Bengal, passed by the Governer General in Council on the 1st May 1793. Cited in Acharyya Bijay Kisor. Codification in British India. Calcutta, S.K. Banerji & Sons.

- “A Speech Delivered in the House of Commons on the 10th of July, 1833”, in Lord Macaulay, The Miscellaneous Writings and Speeches of Lord Macaulay (London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1889).

- Kolsky, Elizabeth. “Codification and the Rule of Colonial Difference: Criminal Procedure in British India.” Law and History Review 23, no. 3 (2005): 631–83. doi:10.1017/S0738248000000596.

- supra note 2

- The Anglo-Indian Codes: Adjective law. United Kingdom: Clarendon Press, 1888.

- Section 53, Charter Act, 1833

- The Anglo-Indian Codes: Adjective law. United Kingdom: Clarendon Press, 1888.

- Law Commission of India, Twenty-Seventh Report, December, 1964. The Code of Civil Procedure,1908.

- See the “Humble Memorial of the Anglo-Indian and European British subjects residing at Mirzapur in Upper India,” in Extra Supplement to the Gazette of India, July–December 1883.

- See letter No. 1232 J-D. from F. B. Peacock, Secretary to the Government of Bengal, to the Government of India (Legislative Department), dated June 22, 1883, in Extra Supplement to the Gazette of India, July–December 1883.

- Yelle, Robert A.. The Language of Disenchantment: Protestant Literalism and Colonial Discourse in British India. United Kingdom: OUP USA, 2013.

- Cohn, Bernard S.. Colonialism and Its Forms of Knowledge: The British in India. United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 1996.

- Ibid., Cohn, Bernard S.. Colonialism and Its Forms of Knowledge: The British in India. United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 1996.

- DeSousa, V. (2008). Strategies of Control: The Case of British India. Sociological Viewpoints, 24, 61-74. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/strategies-control-case-british-india/docview/221250743/se-2

- Kolsky, Elizabeth. “Codification and the Rule of Colonial Difference: Criminal Procedure in British India.” Law and History Review 23, no. 3 (2005): 683. doi:10.1017/S0738248000000596.