Big Agro and the Seed Monopoly

10 March, 2024

1570 words

share this article

The intersection of agriculture, economy, and the environment has never been more critical or contentious than it is in the era of big agro and seed monopolies. As the world’s population continues to grow, so does the demand for food, pushing the agricultural sector to find more efficient, higher-yielding methods of production. However, this drive for efficiency has led to a concentration of power in the hands of a few multinational corporations that control a significant portion of the seed market. This essay examines the implications of this concentration of power for the environment, soil health, farmers, and the quality of agricultural produce.

Big Six to Big Four

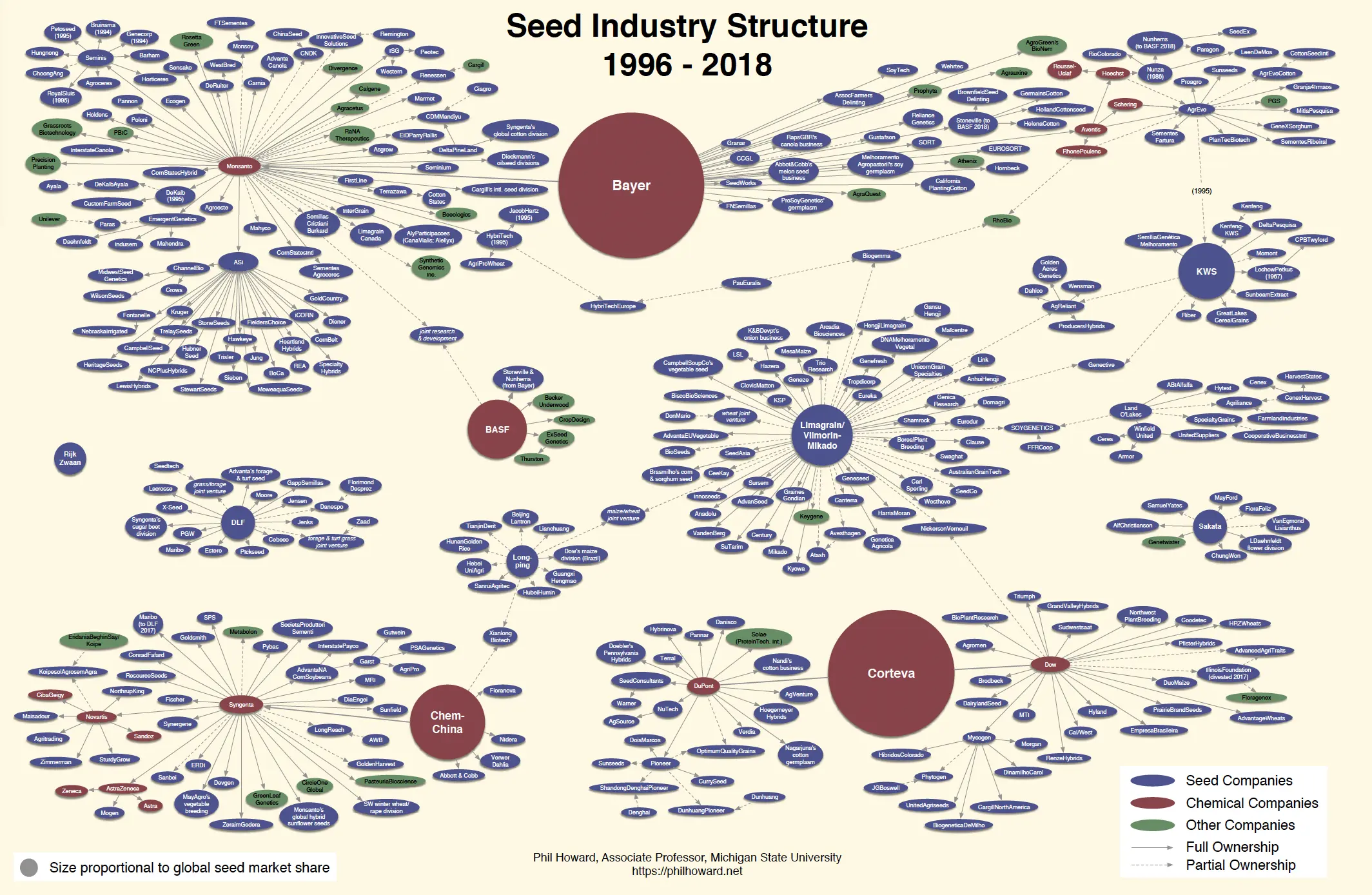

Following the chemical and industrial revolution, the agricultural sector has seen a dramatic shift towards consolidation, with a handful of companies now controlling the global market for seeds and agricultural chemicals. This consolidation has been driven by several factors, including the development of genetically modified organisms (GMOs), the patenting of seed varieties, and the vertical integration of supply chains, creating oligopolies. The Big Six have now consolidated as the Big Four: Corteva Agriscience split from DowDuPont, and Chemchina was acquired by Syngenta for $43 billion. Monsanto is now part of Bayer, whose seed divisions (including the Stoneville, Nunhems, FiberMax, Credenz and InVigor brands) were sold to BASF (a European multinational chemical company) for $7 billion to satisfy antitrust regulators in 2018. These multinational companies seem to be associated with everything that is diabolical about modern agriculture.

In 2016 it was announced that Bayer, which generates $10.2 billion of its $51.8 billion revenue from seed and agrochemical revenues, acquired Monsanto, which generates all of its $13.5 billion revenue from seed and agrochemicals, in a $63 billion merger. The merger was essentially a move that successfully disassociates the negative press and pushback worldwide from the Monsanto name, while continuing business as usual under a different head. The Big Four, allocate substantial financial resources towards lobbying efforts, securing governmental backing for their nefarious activities such as lobbying and agrochemical pollution. In 2016, Dow invested $200,000 in agricultural lobbying, whereas Syngenta expended $940,000. This consolidation and formation of more entrenched oligopolies is also a cultural and economic issue. It undermines the values of food producers and consumers globally. These oligopolies bulldoze the many communities that champion principles of empowering individuals, supporting small enterprises, and upholding the freedom to engage in farming and self-sustenance without reliance on the products of industrial agriculture or the dominance of merely four major corporations.

Environmental Impact

One of the most significant concerns with the dominance of big agro is its impact on the environment. The model of industrial agriculture promoted by these companies relies heavily on monoculture (cultivation of only a single type of crop in a given area), which can increase short-term yields, but also have the net effect of soil depletion, reducing biodiversity, soil depletion, making ecosystems vulnerable to pests and diseases, increased consumption of water, and an increased application of chemical pesticides, weedicides and fertilizers. These chemicals further contaminate water supplies, harm non-target species, and contribute to the decline of pollinators like bees and butterflies.

Adverse effects of GMO seeds

Seed varieties cannot be patented in India; however, this does not stop foreign companies from dominating the market with patented seed varieties. It is a misconception that genetically modified organism (GMO) seeds greatly impact yield, and it is alarmist to assume that there would be food scarcity if developing nations attempted to reduce their dependence on GMO varieties. Apart from their adverse effects on our health, they also adversely impact indigenous farming traditions and local genetic biodiversity of plants. GMO seeds often require farming methods that are incompatible with indigenous knowledge and techniques honed over generations. This shift not only undermines cultural heritage but also displaces small-scale farmers who cannot afford the high costs associated with GMO seeds and the requisite chemical inputs. Furthermore, the widespread adoption of GMO seeds exacerbates the loss of genetic biodiversity, as these engineered varieties supplant a multitude of local species that have been naturally selected for their resilience to local pests, diseases, and climatic conditions. The loss of such genetic diversity diminishes the resilience of food systems, making them more vulnerable to pests, diseases, and the impacts of climate change, thereby threatening food security and sovereignty especially in developing nations. Moreover, market dominance also de-incentivizes companies to innovate, with their priority instead being the farming of emerging markets for seeds and the expansion of profit margins.

Impact on Soil

Soil is the foundation of the food chain in terrestrial ecosystems, and its health is crucial for the sustainability of agriculture. However, the agricultural practices promoted by seed monopolies have often prioritized short-term gains over long-term soil health. The heavy use of chemical inputs and the focus on monocultures have led to soil erosion, reduced biodiversity, and decreased fertility. These practices disrupt soil structure and reduce the population of beneficial microorganisms, which play a critical role in organic matter decomposition and nutrient cycling. Furthermore, the patenting of genetically modified seeds has led to a reduction in seed diversity. Farmers, under contract with these large corporations, are often restricted to planting patented seeds, which can further exacerbate soil degradation. Diverse cropping systems, including crop rotations and intercropping, are essential for maintaining soil health, but such practices are not always compatible with the business models of seed monopolies.

Impact on Farmers

The control of the seed market by a few corporations has profound implications for farmers around the world. One of the most immediate effects is the increased cost of inputs, coupled with less choice and higher prices. As these companies have consolidated their control over the market, they have been able to raise the prices of seeds and chemicals, squeezing farmers’ margins and making it increasingly difficult for smallholders to compete. The use of patented seeds restricts farmers’ traditional practices of saving and exchanging seeds, forcing them to purchase new seeds each season. This not only increases dependency on a few multinational corporations but also erodes agricultural biodiversity in the marketplace and the landscape, which is vital for food security and resilience against pests, diseases, and changing climate conditions. Farmers also face legal challenges from these corporations, which have been known to sue for alleged patent infringements (such as PepsiCo’s lawsuit against four Gujarati farmers in 2019 for growing a patented variety of potato), further entrenching their power and influence over the agricultural sector. These practices have led to increased farmer indebtedness in some regions, contributing to social and economic distress in rural communities.

Impact on Quality of Agricultural Produce

The dominance of seed monopolies and the agricultural practices they promote can also affect the quality of agricultural produce. The focus on high-yielding, genetically uniform crops can lead to a reduction in the nutritional quality of food. Studies have shown that fruits and vegetables today may contain fewer vitamins and minerals than those grown in past decades, partly due to the selection for varieties that prioritize yield over nutritional content. Furthermore, the heavy use of chemical inputs in industrial agriculture can lead to residue accumulation in food, raising concerns about long-term health effects. While regulatory bodies set limits for pesticide residues, the cumulative effect of multiple chemicals and their potential for interaction raise questions about the adequacy of current safety assessments.

Countering the Effects of Big Agro, One Farmer at a Time

SOUL Society for Organic Living, started by Tarachand Belji, has created a method to enable the easy adoption of organic/natural farming practices, improving soil health and fertility and ensuring quality produce. The organization caters to the end-to-end management of organic farming practices by providing organic agricultural input products and education, advice and training to farmers. Small-scale resistance movements such as these prove that Bhārata, which has its own indigenous knowledge systems and experience when it comes to agriculture, need not be reliant on the products or techniques advocated by big agro chemical companies, multilateral organizations and global lobby groups in order to successfully produce a high yield of high quality produce. Moreover, the practices reduce dependency on patented seed varieties and inorganic chemicals, decreasing the burden on the state, which subsidizes these inputs for farmers. Through its focus on farmer support, education and awareness, and their able hand-holding of farmers through the transition period, SOUL’s methods and callback to ancient Indian wisdom have been catching on and have the potential to mount a significant response to the global agrochemical nexus.

Conclusion

The consolidation of the seed industry and the rise of big agro have profound implications for the environment, soil health, farmers, and the quality of agricultural produce. While these companies have contributed to increases in agricultural productivity, the long-term sustainability of their practices is increasingly questioned. Addressing these challenges will require a concerted effort from policy makers, governments, the private sector, and civil society to promote more sustainable agricultural practices, protect biodiversity, and ensure that the benefits of agricultural innovation are widely shared. As the world continues to grapple with ecological degradation and reduced human health and nutrition, rethinking the current trajectory of industrial agriculture is not just desirable but necessary.

References

- Prb. (2022, January 5). The big six to the big four: The rise of the seed and agrochemical oligopoly. Policy Review @ Berkeley.

- Global Seed Industry Changes Since 2013

- Hubbard, K. kiki. (2021, January 14). The sobering details behind the latest seed Monopoly Chart.

- SOUL Society for Organic Living